Think about computers as if they were children and it’s simple to understand how coders can teach them to learn. Artificial intelligence is, at the beginning, very basic and simple. Human moderators instruct computers, showing them how to think and thus teach themselves. Once the coders give them the basics, though, they can expand that knowledge quickly.

“What can you do with 7 million digital artifacts?”

At the Google Cultural Institute in Paris, France, the search giant is teaching machines how to categorize 7 million images of human artistic achievement throughout the centuries. The Institute even has a website, as well as apps for iOS and Android where you can search through works of art from different museums around the globe. To create its catalog of art, the code artists in residence at the Institute had to teach computers to view images the way humans would to create an accurate digital archive of art throughout human history.

Cataloging history is well and good, but some of the skills computers are learning from sorting and filing are actually making them more creative. The artists in residence are now experimenting with computers to create new works of art using machine intelligence and the catalog of 7 million images they’ve pieced together. During Google I/O 2016, Cyril Diagne and Mario Klingemann explained how they’ve taught machines to see art like humans, and how they’ve trained machines to be creative.

Teaching computers their ABCs

One of the first things you teach a child is language. In Western culture, that means learning your ABCs. Mario Klingemann, a self-described code artist from Germany, started teaching machines to identify stylized letters from old texts to find out if he could teach a computer to recognize thousands of different-looking As, Bs, Cs, and so on. It was a crash course in teaching machines how to categorize images the way humans would.

While a computer may look at a stylized letter B covered in vines and flowers and see a plant of some kind, even a 5-year-old child could immediately identify the image as a letter B — not a plant. To teach his computer to recognize its ABCs, Klingemann fed it thousands of images of stylized letters. He created a Tinder-like interface of swiping right or left to tell his machines if they guessed the letter right or wrong.

It turns out, machines do learn their ABCs pretty quickly; they started seeing letters in everything. Just as humans see faces in clouds and images in abstract artwork, his computers saw letters in completely unrelated images. Klingemann showed his computer a drawing or etching of a ruined building, and they saw a letter B instead.

Klingemann explained that when you train a computer with only one set of images, it starts to see only that kind of image in everything. That’s why his machines saw a letter in a ruin.

Teaching computers to categorize 7 million images

When Digital Interaction Artist Cyril Diagne joined the Cultural Institute, Google posed a rather daunting question to him, “What can you do with 7 million digital artifacts?”

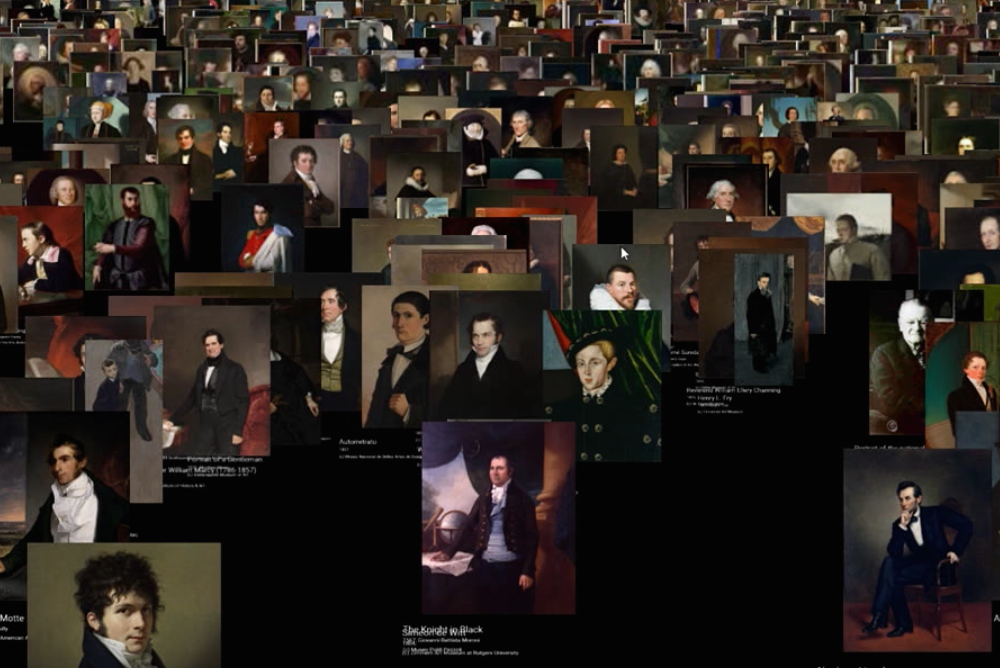

Diagne was overwhelmed by the question, so he charted every image in a gloriously massive sine wave, which you can see below. That wave later ended up becoming a beautiful representation of everything the project hopes to accomplish with machine learning. Diagne’s sine wave is actually searchable, so you can surf a sea of all the images in the digital archive made by the Google Cultural Institute. Images are grouped in categories, and from a bird’s eye view, you just see a sea of dots. As you move in, you can see specific images, all with a common theme, whether it’s puppies, farms, or people.

You can search through it, too, and find the images you want. If you look hard enough, you might even run into what Diagne calls the Shore of Portraits. That’s where all the images of people’s faces are clustered.

To make the searchable map of every image in the archive, Diagne and his team had to create a category for everything to teach the machine what was what.

Categorizing 7 million artifacts, many of which may have multiple categories, is no easy task. The team had to think up some that were outside the box. It’s not enough to just categorize things based on what they are. They also had to create categories for the emotions that images evoke.

Teaching machines human emotions is an important step toward making them more creative.

That way, you can search for an image of “calm,” and the computer will show you images that evoke a sense of calm, like sunsets, serene lakes, and so on. Amazingly, the machines learned how to identify human emotions with such skill that they can put themselves in our shoes to consider how a certain image would make a human feel.

Teaching machines human emotions is an important step toward making them more creative. After all, much of modern art is visual representations of human emotions.

But can a machine be creative?

Creativity and artistry are two things that we humans like to think of as ours alone. Animals don’t make art, nor do machines … yet. Google’s Deep Dream project attempted to turn the notion that machines can’t create art on its head. The search giant trained computers to manipulate images to create bizarre, psychedelic works of art. The images created by Google’s Deep Dream engine may not be pretty, but they certainly are unique and wildly creative. Machine creations contain psychedelic colors, slugs, weird eyes, and disembodied animals swirling in undefined spaces.

Some may argue that it’s not really art if machines are just combining existing images, twisting them, and dipping them in extreme colors; Google would beg to differ, and so would code-artist Klingemann.

“Humans are incapable of original ideas,” he explained.

Even famous paintings contain elements of previous artwork, he noted. Picasso’s 1907 masterpiece Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, for example, has influences from African art and precursors to cubists like Paul Cezanne. For that matter, collages, which combine existing images in an artistic fashion, are another well-established art form. Picasso, Andy Warhol, Man Ray, and more are known for their eccentric collages, so why can’t collages made by machines also stand as art?

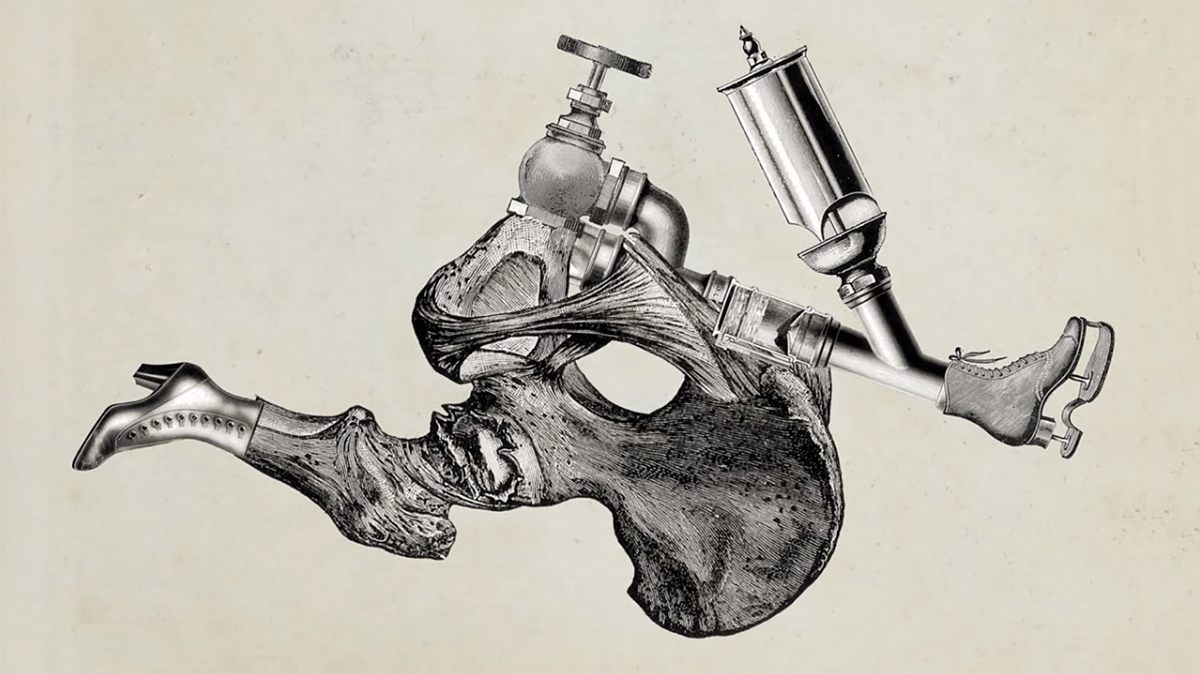

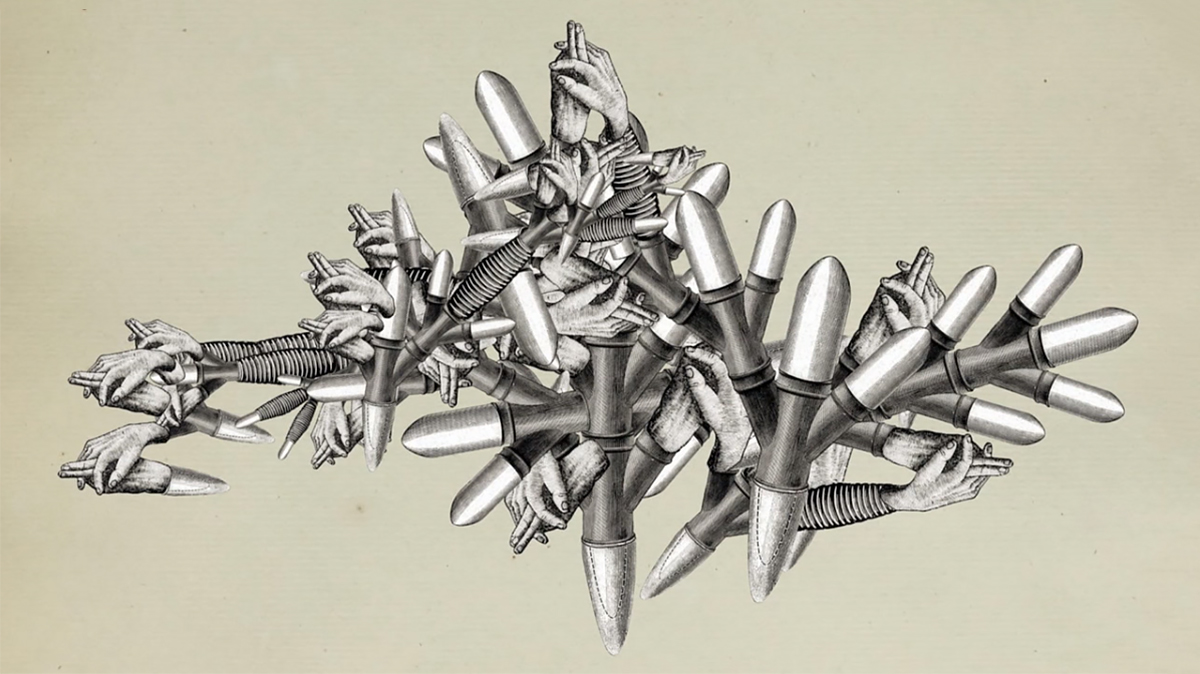

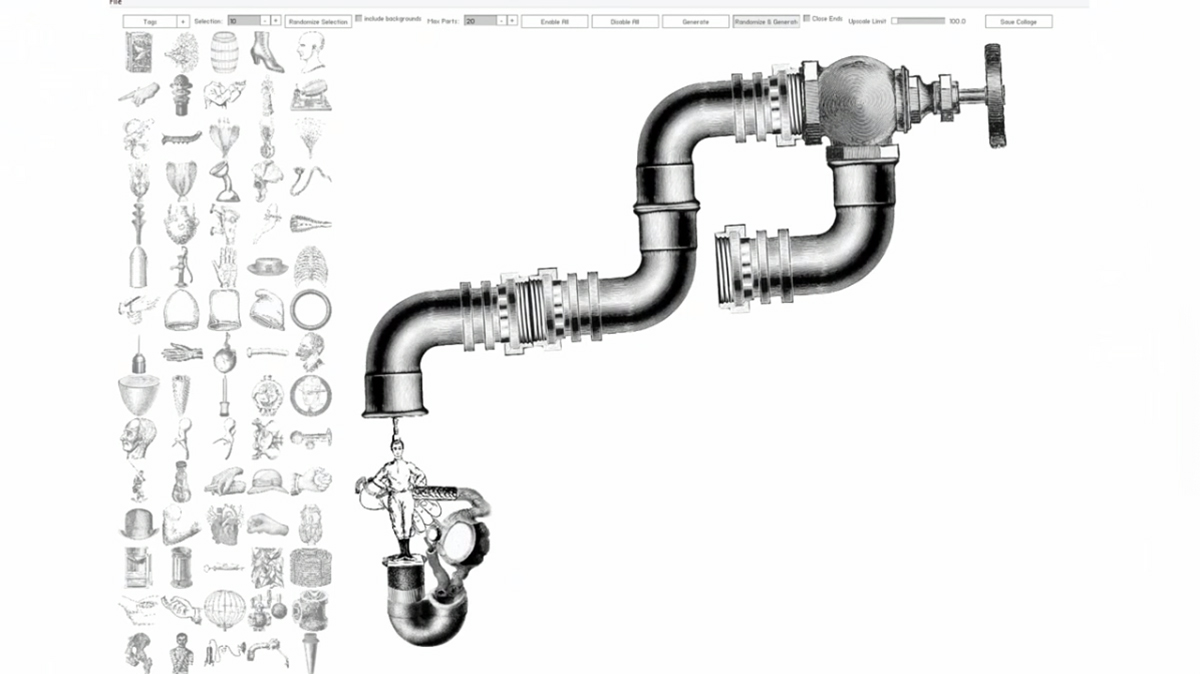

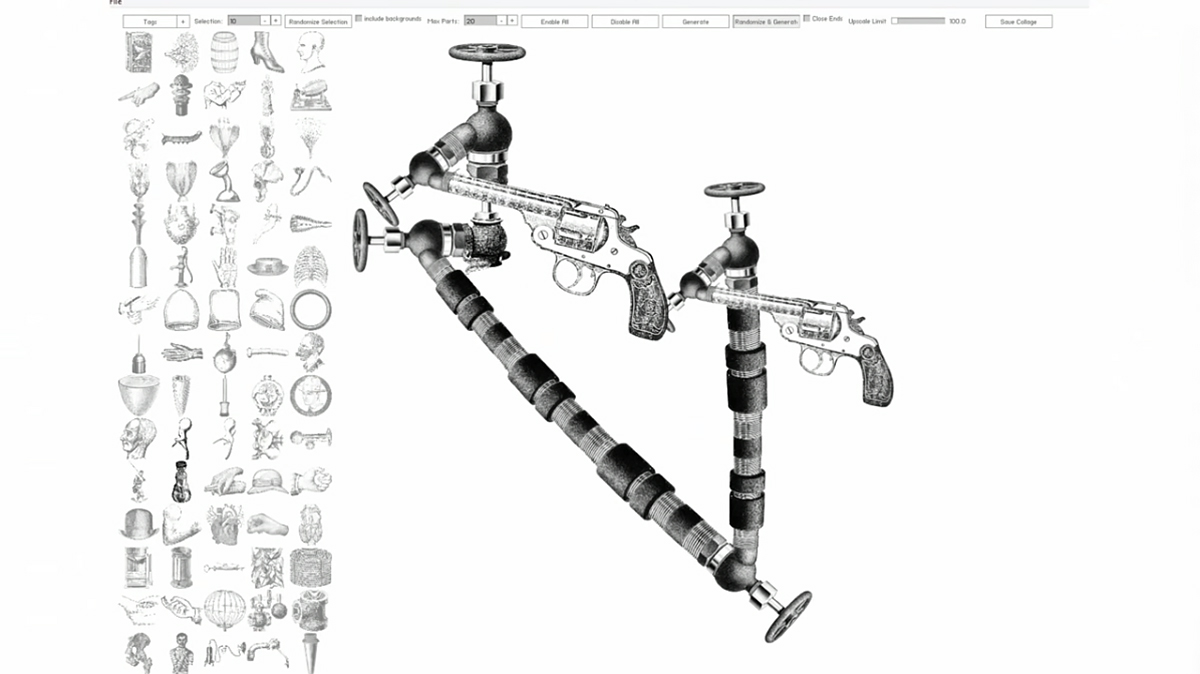

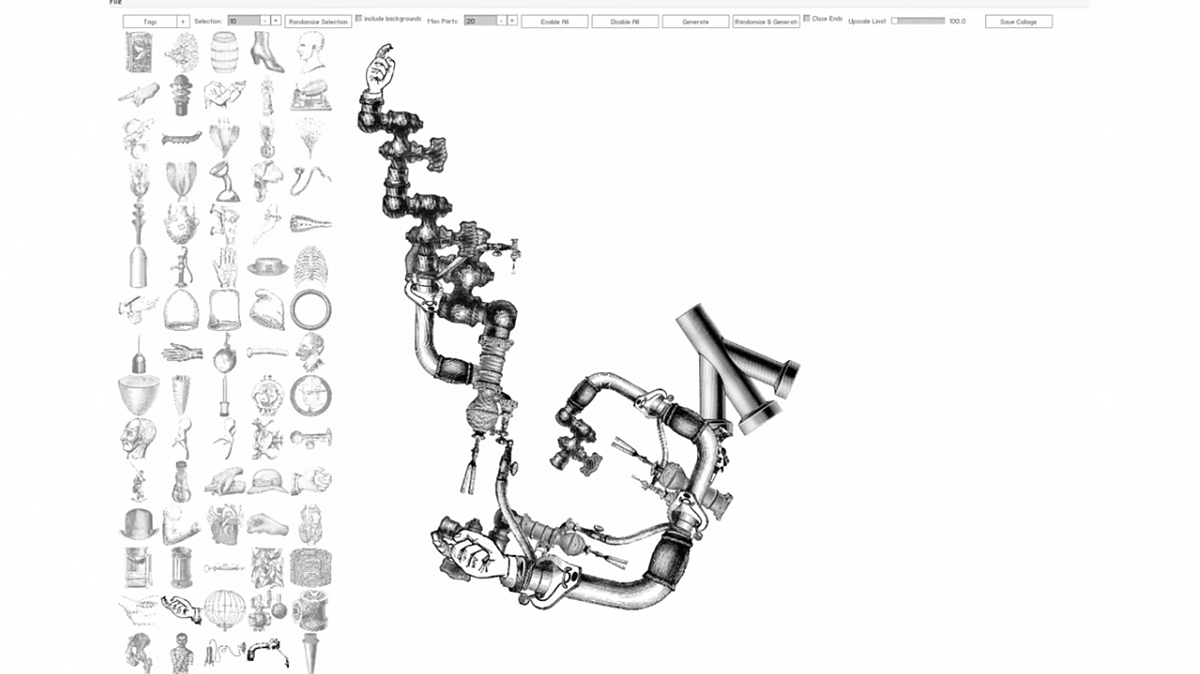

Klingemann wanted to push the boundaries of digital art and see how creative machines could get long before he started his residency at the Google Cultural Institute. Using his own less powerful machines, Klingemann started playing around with the Internet Archives and Google’s TensorFlow machine learning software to make digital collages.

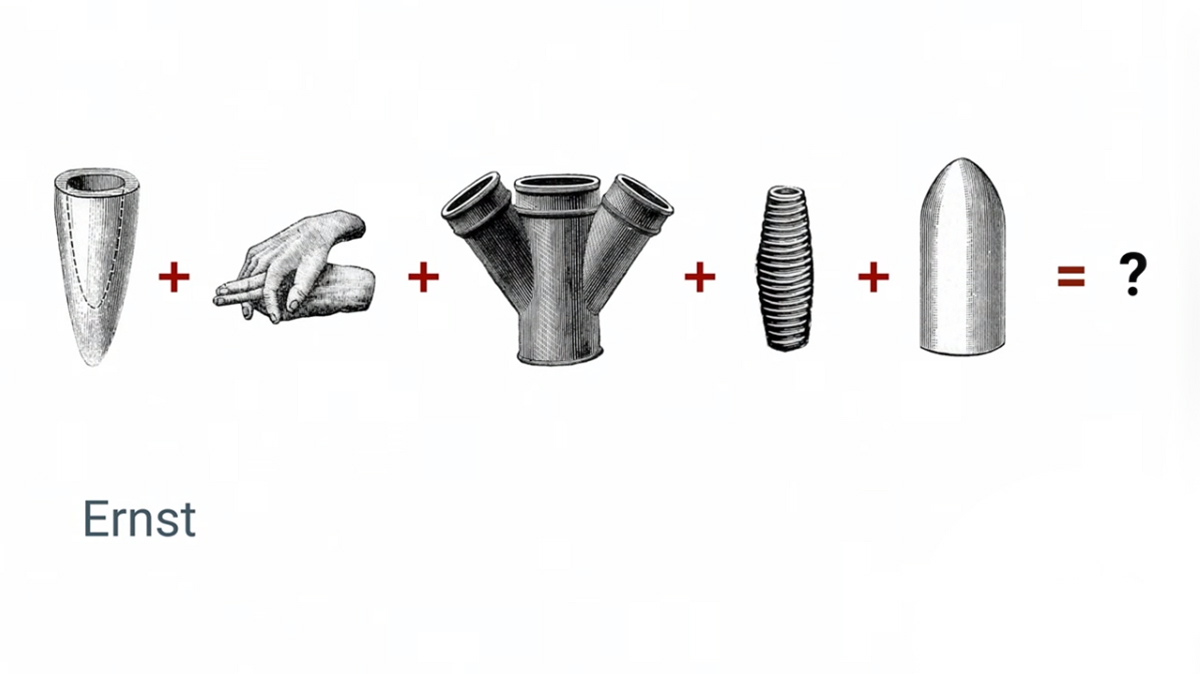

He created a machine-learning tool called Ernst, named after the surrealist and collage artist Max Ernst. Klingemann identified a series of objects from Ernst’s work and told his computer to make different collages with the same elements. The results were often surreal, sometimes funny, and at other times, absolutely terrible.

“Humans are incapable of original ideas.”

Klingemann wanted more control over the chaotic images his machines were producing, so he started teaching them new things. He asked himself, “What is interesting to humans?” Klingemann knew he had to train the system what to look for, to teach it how to view all those elements like a human artist would.

The resulting artwork is gorgeous and entirely unique. Although Klingemann obviously used old images to create his work, they’re displayed in a new context, and that makes all the difference.

Right now, computer creativity is limited to interesting collages and understanding which images go well together. Machines aren’t making their own art yet, but the code artists who power them are becoming more curator than creator during the process.

It remains to be seen how far man can expand the creative minds of machines, but it certainly is fascinating to watch.

Editors' Recommendations

- How to generate AI art right in Google Search

- Google Bard can now speak, but can it drown out ChatGPT?

- You can now try out Google’s Bard, the rival to ChatGPT

- Google’s new Bard AI may be powerful enough to make ChatGPT worry — and it’s already here

- These 7 AI creation tools show how much AI can really do