“We [have] developed a sperm-hybrid micromotor by using sperm for the first time as drug carrier, and a microscale structure as magnetic guidance mechanism and flexible release trigger,” Haifeng Xu, a researcher with the Leibniz Institute’s department of micro and nanostructures, told Digital Trends.

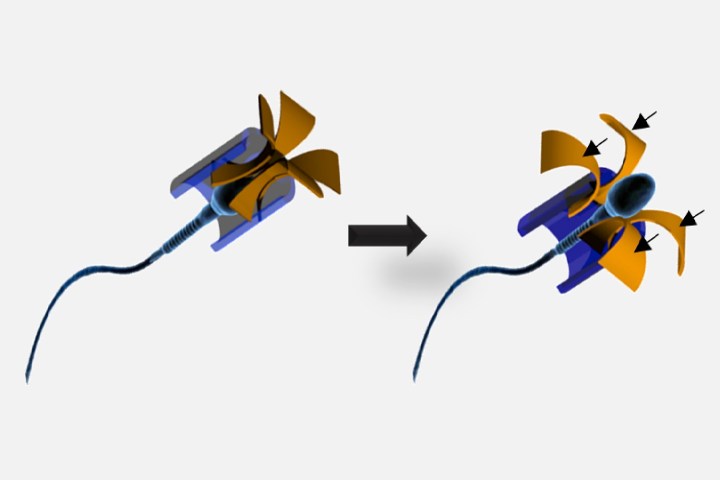

The approach involves loading up sperm cells with a common chemo agent called doxorubicin, then fitting the sperm with miniature four-armed magnetic harnesses, and controlling their movement via magnets. When the sperm hits a tumor, the magnetic harnesses open up and the sperm swims into the tumor to deliver its contents.

“Compared to existing dose forms, the main advantages of this system are the drug protection by the sperm membrane, tissue penetration by the sperm flagella, drug uptake enhancement due to the cell-fusion ability of the sperm, and the precise guidance based on the magnetic microstructure,” Xu continued.

In a Petri dish experiment, the customized sperm was shown to be capable of killing 87 percent of mini cervical cancer tumors within a period of three days. We’re not sure exactly how this technique would be extrapolated to humans, but the hope is that it could provide an alternative to the more toxic side effects of regular chemo, which can include extreme nausea.

“So far, we have confirmed the cancer cell-killing capability of drug-loaded sperms in in vitro experiments, and successfully guided a sperm-tetrapod micromotor toward in vitro tumor target to induce cell death,” Xu said. “[The] next step will be the investigation of real-time imaging of micromotors under deep tissue, and operating a micromotor cluster.”

A paper describing the work, titled “Sperm-Hybrid Micromotor for Targeted Drug Delivery,” was recently published in the journal ACS Nano.

Editors' Recommendations

- Nvidia’s GPUs could smash AMD in the next-gen performance war

- Tiny bubbles in your body could be better at fighting cancer than chemotherapy