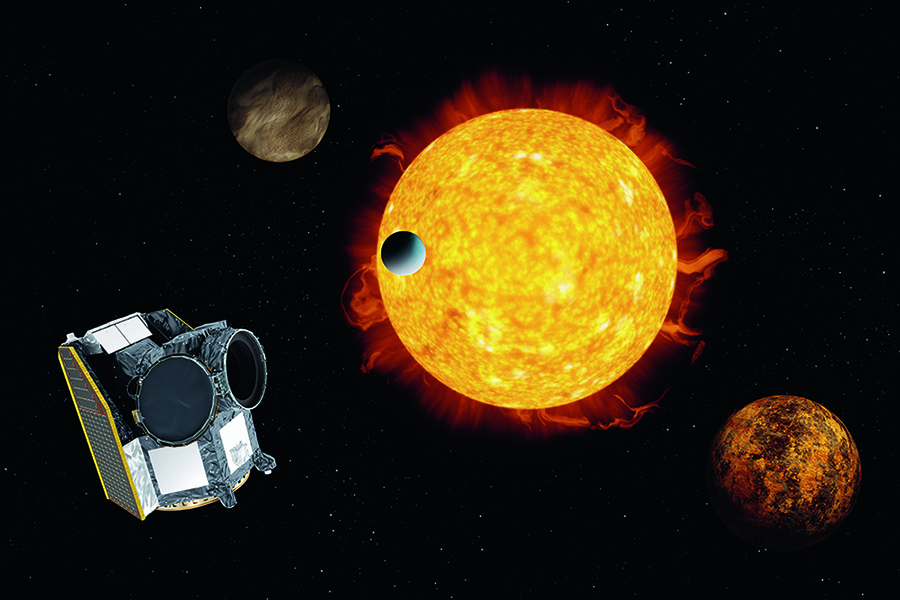

The European Space Agency (ESA)’s new exoplanet-hunting satellite, CHEOPS, has taken its first image of a target star. The satellite was launched in December last year and opened the cover to its camera last week, and now it has begun imaging distant stars to search for telltale signs of planets orbiting around them.

Waiting for the first image was somewhat fraught for the scientists working on the project, as they could not be sure that the camera and other instruments were working perfectly until they saw the data come in.

“The first images that were about to appear on the screen were crucial for us to be able to determine if the telescope’s optics had survived the rocket launch in good shape,” explains Willy Benz, Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Bern and Principal Investigator of the CHEOPS mission. “When the first images of a field of stars appeared on the screen, it was immediately clear to everyone that we did indeed have a working telescope.”

The captured image, shown above, may look rather blurry. But this isn’t a mistake or a problem — the telescope is deliberately defocused. Counterintuitively, this actually makes the image more precise as the light from sources like stars is spread over more pixels, which lessens the variations caused by the movements of the spacecraft.

“The good news is that the actual blurred images received are smoother and more symmetrical than what we expected from measurements performed in the laboratory,” Benz explained. “These initial promising analyses are a great relief and also a boost for the team.”

CHEOPS detects exoplanets through the transit method, in which it monitors the brightness levels of stars to look for periodic dips. If there are regular dips in brightness, that suggests that something — like an exoplanet — is orbiting around the star and periodically blocking its light. This is the same method used by NASA’s planet-hunter, TESS.

With CHEOPS capturing images, there will be more tests of its systems over the next two months to ensure everything is working smoothly. “We will analyze many more images in detail to determine the exact level of accuracy that can be achieved by CHEOPS in the different aspects of the science program,” said David Ehrenreich, CHEOPS project scientist at the University of Geneva. “The results so far bode well.”

Editors' Recommendations

- NASA’s anti-asteroid DART mission sends back its first images

- Hawaiian telescope snaps an image of a recently formed baby planet

- Watch the European Space Agency test the parachute for its new Mars rover

- China’s Zhurong rover beams back its first Mars images

- Here’s what the James Webb Space Telescope will study in its first year