Some of the voice disorders the team was interested in were ones that can lead to the formation of nodules or polyps on a person’s vocal cords, which can interfere with regular speech production. This effect is sometimes seen in singers, teachers, or people in other jobs which require them to use their voice at high intensity for prolonged periods.

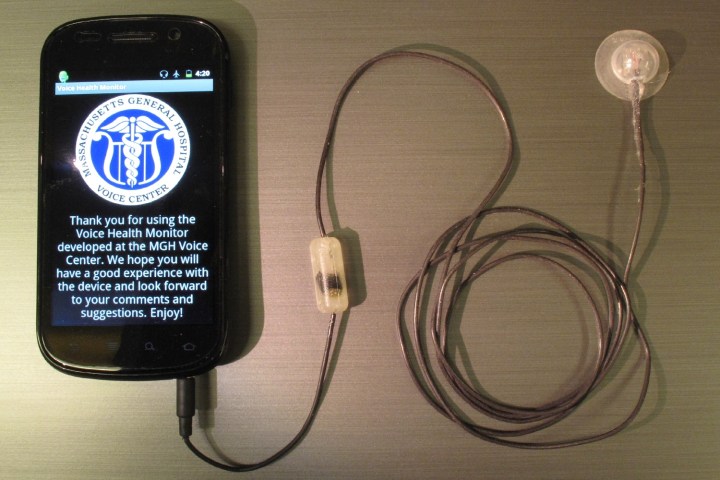

By creating a noninvasive wearable accelerometer able to be plugged into a regular smartphone, MIT researchers think they could have an important diagnostic tool on their hands.

“We’re not measuring speech, but rather measuring the movement of a person’s vocal cords through their neck,” MIT doctoral student Marzyeh Ghassemi told Digital Trends. “This could be important for privacy, since it’s not picking up sound. I can imagine people might be uncomfortable wearing a tool like this for a week in their home if it was recording what they were saying — but we’re taking a different approach.”

In the study, subjects were divided into one of two groups: either patients with diagnosed voice disorders or a control group without such problems. They then wore the accelerometers during their daily activities, capturing 110 million “glottal pulses,” referring to each opening and closing of a subject’s vocal folds. Using machine learning, the researchers were then able to use this data to come up with a system capable of distinguishing between those with vocal disorders and those without.

Rolled out into the real world, such tools may be used to help diagnose a variety of vocal disorders, or to test the efficacy of treatment. “This type of accelerometer signal does have a lot of potential for being used in the future for diagnosing all sorts of conditions,” Ghassemi continued.

Together with its privacy “selling point,” this could turn out to be one heck of a useful tool for clinicians worried about particular patients.

Editors' Recommendations

- Optical illusions could help us build the next generation of AI

- Kid-mounted cameras help A.I. learn to view the world through eyes of a child

- A brain scan could help reveal if antidepressants will work for a patient

- Yakuza director thinks PS5’s evolution will focus on A.I. and machine learning