Most video games tend to operate under a fairly simple set of rules: you have a set of play mechanisms and rules that exist in the service of driving players toward some sort of objective. Story is secondary, even in games like BioShock Infinite in which significant time and effort was clearly put into crafting an impactful narrative. What if it wasn’t though? What if the audio recordings in BioShock game were in fact the focus of your journey from Beginning to End?

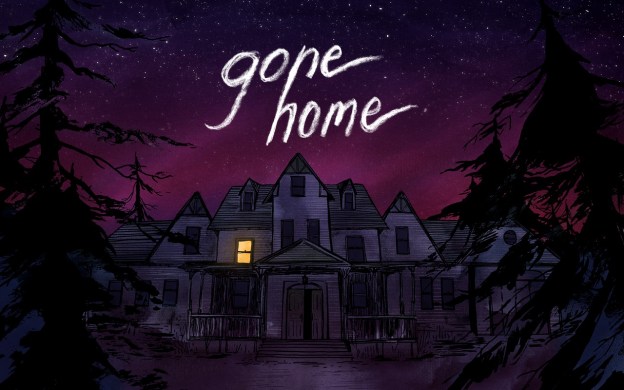

This is the line of thinking that led 2K Marin and Irrational Games veteran Steve Gaynor to found The Fullbright Company, a Portland-based indie studio that is currently hard at work on its first game, Gone Home. The game sets players loose in an empty suburban home on a “Dark and Stormy Night.” The setup establishes the main character as the eldest daughter in a family of four – mother, father, two daughters – who returns home after a year abroad to find everyone missing. The phones are out and the inclement weather makes leaving impossible, so you’re left to explore the house and try to piece together what happened.

Gone Home delivers its story in an unusual way, but it makes a lot more sense when you consider the backgrounds of Fullbright’s three founder. Gaynor served as a level designer on BioShock 2, and as the writer and lead designer on that game’s campaign DLC, Minerva’s Den. He then went on to put in a year at Irrational while Infinite was in development, and those combined experiences working with material from one of the industry’s most creative storytellers left him with some fresh ideas.

“I got to work [at Irrational] with guys who made a bunch of my favorite games – I mean, they’ve been shipping amazing shit for 15 years – I learned a lot,” Gaynor told us in a rapid-fire interview on the crowded show floor at GDC 2013. “I did my year and I hope I contributed, but then my wife and I decided to move back to Portland. There’s not really a big, established game industry in Portland so you kind of have to do your own thing.”

“It is the kind of experience that is usually a sideshow in a big AAA game…”

“We’re really excited to be making this small game. Making DLC is like a small team/small game experience, but within a much larger organization,” Gaynor explained. “It’s great to have that support and that access to a bunch of people with expertise in the building, but part of our motivation for doing Gone Home is, we want to have that small team experience. We want to make something that we’re 100-percent invested in.”

With three BioShock veterans forming the founding heart of Fullbright, it wasn’t long before their ‘What’s our first project?’ conversation turned toward the narrative. The Fullbright trio’s past work experience informed the discussion, and all of them agreed that the idea of telling a story built entirely out of environmental cues is a compelling one. “You piece the story together yourself by finding these little bits of voice and writing and objects,” Gaynor said of the core idea. “This kind of distributed narrative where you’re finding the dots in the constellation and connecting them.” That doesn’t make a whole game though… but what if it did?

“It is the kind of experience that is usually a sideshow in a big AAA game,” Gaynor continued. “In a big game, what do you do? You fight enemies and do mission objectives and collect loot… and also there’s a story there to be discovered. We thought… what if that becomes the main attraction? It’s the only thing that the game is about.”

Other pieces fell into place quickly from there. The small size of the team was important in helping to quickly address some very basic questions: Gone Home‘s empty house is explored entirely from a first-person perspective, which means there was no need for character artists, animators, or AI programmers. The scale decision came quickly as well: four people limits the amount of virtual real estate that can be crafted in a realistic amount of time, so the decision was made to instead build a single house and pack it tightly with things to find. “Then we would basically get the most out of every square foot that we build,” Gaynor explained.

Setting was another important question to be answered, with Fullbright eventually deciding on June 1995. “We wanted to make a game that was as close to the player’s own experience as possible. As familiar as possible,” Gaynor said. Unfortunately, a straight-up present day setting creates some narrative issues that would have been difficult to address for the sort of experience that Gone Home aims to deliver.

“What we want you to do is explore throughout the whole house and find bits and pieces scattered around [that fill out the story],” Gaynor explained. “If it’s set now, you find one character’s cellphone and go through their text messages and you know what’s up. For us it was a very practical decision, as far as how it started, with us saying, ‘How recent can it be without having the digital communication problem?’ 1995. Maybe this family doesn’t have AOL yet. People would still actually write each other letters and leave notes on the kitchen table saying ‘I’m going to be late tonight.’ You can find all of that tangible, handwritten evidence scattered throughout the house.”

The basic idea squared away easily enough, but some narrative conceits were still necessary in order to make Gone Home‘s story really make sense. The “dark and stormy night” setup is undeniably trite, but it exists in service to the story here. The phones are out. The airport shuttle bus is gone and the weather outside is too nasty to walk to the nearest police precinct. The narrative contrivance is justified within the fiction of the game. It also lends a lot of ambience to the actual play experience; even when there’s nothing overtly spooky happening in Gone Home, there’s this sense of quiet menace pervading everything as thunder and lightning crash outside.

The experience that’s been built so far bears Gaynor’s words out. The first act was available to play at GDC’s IGF Pavilion, and while we weren’t able to sit and explore all of it, enough time was spent to get a sense of what this game has to offer. Gone Home might throw out the familiar video game rulebook, but it seems to deliver on its promise of turning AAA’s favorite sideshow into your raison d’etre.