“I want the fans to hear what we hear in the studio. Forget about TV, laptops, and elevators — who cares?”

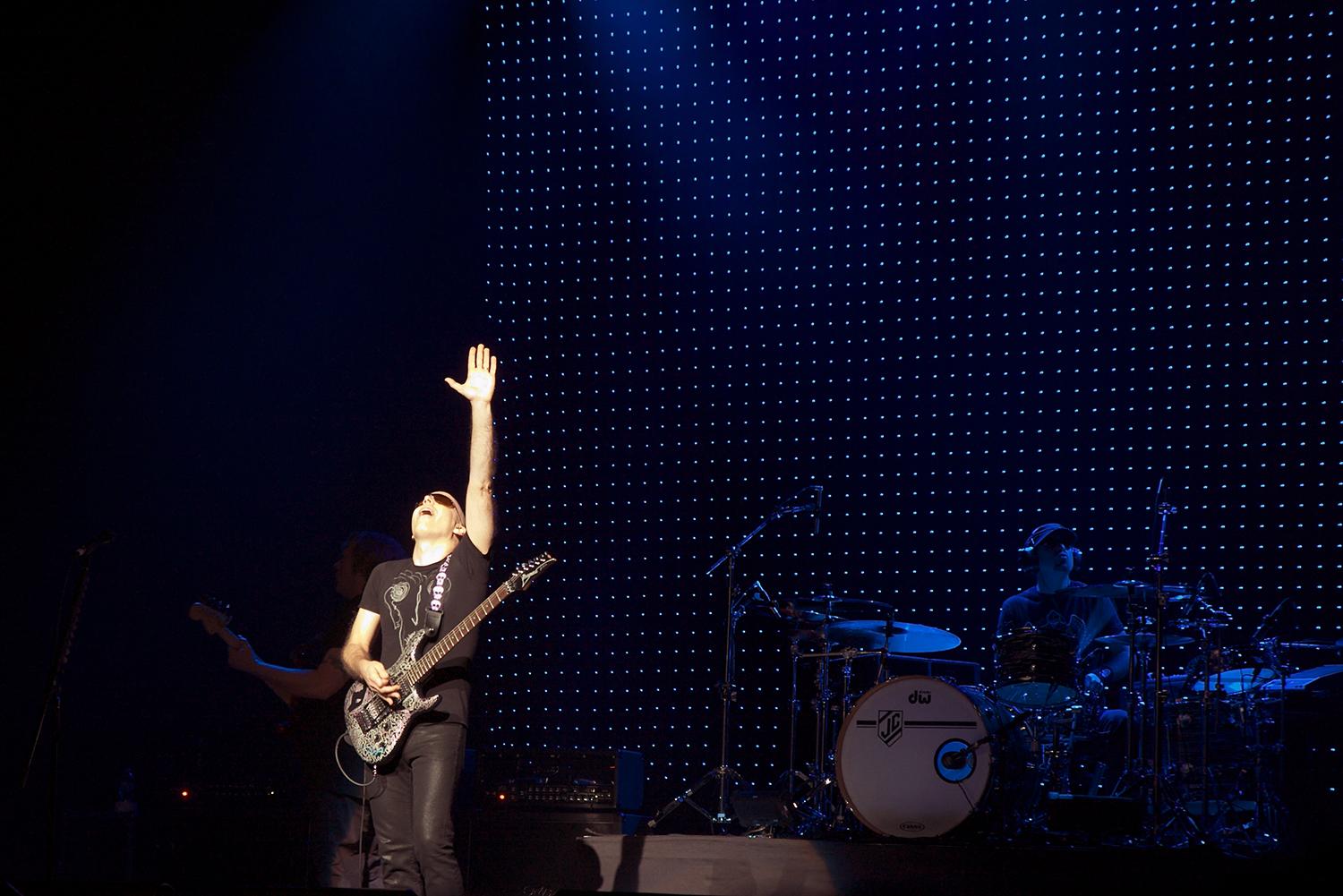

When it comes to modern-day guitar gods, Joe Satriani is in the upper pantheon. Satch, as he’s also known, is a melodic shredmaestro who was able to bridge the gap between niche noodling and mass acceptance with massive sellers like 1987’s Surfing With the Alien — an album also notable for having Marvel’s indelible (and similarly chrome-domed) cosmic traveler the Silver Surfer on its cover.

He continues to spread his unique brand of six-string magic on sold-out tours all across the globe, but when he came to the end of his two-year-long Unstoppable Momentum tour, Satch knew he needed to make some kind of change. A new alter ego named Shockwave Supernova was born — and with it, a 15-song album of the same name, out today via Legacy on various formats. “The idea really came out of the realization that I was playing guitar with my teeth a lot, and how silly it was,” Satriani says. “It seemed like such a cool idea that all these songs were remembrances — the end product of deep soul-searching by Shockwave, this performer version of me.”

Shockwave Supernova teems with patented out-of-this-world Satch-tastic guitar histrionics — albeit with some additional spice, from the minor-key blues shuffle of San Francisco Blue to the balls-out raucous riffage of Crazy Joey to the backwards twang and warble of All of My Life.

“All of My Life and Stars Race Across the Sky — those are very introspective pieces,” admits Satriani. “I wanted to have something I could really hold onto that would direct me correctly. You get a bunch of songs together, and you go, ‘Look at this pile of 15 songs over here. They’re telling this epic life story — but whose?’ I wouldn’t know if a song belonged or not unless I really believed in this concept. I had to convince myself that each song had a deep meaning within the life of Shockwave Supernova as he realizes, ‘Oh my God, Joe is right — I have to change. I can’t be this teeth-playing guitar player all the time. I need to be more spiritual.’”

Digital Trends recently sat down with Satriani in a midtown Manhattan hotel lounge to discuss the sonics of Shockwave, the perils of competitive mastering, and his views on streaming. Surf’s up, Supernova.

Digital Trends: How would you describe the character of Shockwave? He starts out as a flamboyant and somewhat flashy player, but as the album progresses, his character evolves and ultimately transforms into something, well, beautiful.

Joe Satriani: Yeah, thanks. At the end of the album, on Goodbye Supernova, Shockwave realizes who he is, and then after the song breaks down, he’s reborn, and he goes out a better person. (chuckles) The fact that every song is different in my mind supported the idea that he really didn’t have one identity. He wasn’t like the shred guitar player, or the metal guitarist, or the blues guitarist. He would change.

The album has such a breadth to its dynamic range, which is refreshing. I know you used to have to think more about the Loudness Wars and how things would sound on the radio, so I’m glad to hear you made a deliberate choice to embrace the full audio spectrum here.

From the start, I wanted this album to be very dynamic. I approached [co-producer/engineer] John Cuniberti with the idea: “First of all, I’ve got this crazy album concept…” (laughs) Look, the last couple of records were fun to do, and we were making them to try to be “competitive.” That was the focus.

You try different things with different records. When John and I did Strange Beautiful Music (2002) together, he went down to Bernie Grundman Mastering and he said, “Hey Bernie, what’s the loudest record there is?” Bernie had a Michael Jackson record there and said, “This record is so loud, it’s stupid!” So John asked, “How about we make this record at least as loud as that one, and just see what happens?” John had been meticulous in recording that record, and we thought it had survived quite well.

And with Super Colossal (2006), [co-producer] Mike Fraser and I had mixed it down to 15 ips — you know, quarter-inch tape; we tried all sorts of different things to create excitement.

But this time around, I said, “You know what? I want the fans to hear what we hear in the studio. Forget about TV, laptops, elevators, and what radio stations are telling you — who cares?” We felt like, with this being record #15, are we really competing with somebody on the radio? We made a record where fans can listen to it quietly, and as they turn it up, it gets better and better and better. No matter how loud they turn it up, it never hurts.

One of the things John could count on saying while he was mixing was, “I’m going to make this part a little bit louder.” Ten years ago, if you said that, people would say, “Oh no, we can’t do that! You’ve only got 1 dB to work with!” John had done my “Chrome Dome” box [the 15-disc collection The Complete Studio Recordings, in 2014], and we had kind of wrestled back the dynamic range from all the years of competitive mastering. Shockwave Supernova is the perfect record, because it needed all of the drama the dynamics could give you.

From the artist’s point of view, do you feel high resolution is the best way to listen to music these days?

We’re in the studio 8 hours a day — in the old days, it would have been 12 hours a day; we’ve learned a few things over the years (laughs). We’re listening to high-powered performances, but it’s not fatiguing because things are dynamic.

“From the start, I wanted this album to be very dynamic.”

At home, I’m recording the guitars DI [direct input], and I’m monitoring with Sansamp [bass drivers], or I’m simultaneously listening to one of my amps going DI out or into an old Marshall SE100 [attenuator/speaker emulator]. When John gets the files and we’re with the band, we clean up a guitar that’s too distorted, or if it’s not aggressive enough because the band is playing more aggressive, we can tweak it on the fly. Once we get everyone’s performances, we can go, “Now, should that be an old Fender Harvard [vacuum-tube guitar amp], or should that be a Marshall turned up to 4?” Since John invented the Reamp [guitar amp/tape recorder interface], we can Reamp everything and create what we think is the best sonic picture. Some of the songs have lots of guitar —and if you’re gonna have six guitars, it’s kinda neat to have six different amps that will compliment each other.

It’s also nice to get that live-off-the-floor feel.

Yep! For one thing, John decided not to write any mutes. It’s a very common way to record drummers now — when the snare’s not being hit, the track is muted entirely. I always thought that was kind of ’80-like — you hear everything, and then go back to the snare. Part of the idea was, “Well, this is going to be full fidelity.” Marco [Minnemann, Satch’s drummer] is sitting there, and when he leaves the snare and hits his toms, he’s hearing his snare rattle. So if we don’t do any mutes, then he can do any subtlety he wants. It’s new. The first time you hear it, you think, “There’s something rattling!” (laughs)

Marco is such a dynamic player that you don’t want to hold him back at all in a mix, if you can help it.

(nods) John called me after a couple of hours and said, “You know, the only thing I’ve decided to do is to turn everything up, and show people what Marco was doing, rather than try to get clever and sample and change things.” He was wondering if I was OK with the mixes where we could hear the entire drum kit — the boom, the crack, and the whap of the hi-hat — and I was like,” Yeah! I was there! I was 10 feet away from him, playing!”

We’ve talked about how you wanted to make the overall dynamic range consistent from the beginning to the end of the “Chrome Dome” box set. Now your entire recorded output breathes, after you and John opened it all up. I’m literally flying in my own blue dream because it sounds so much better. (Satch laughs) Some of the earlier records sounded like there was a cone over them, or something.

Isn’t that interesting? There’s no excuse for it, except to say, “I was there in ’89, and that’s what we were doing then. We thought it was cool. I’m sorry!” (laughs) There is a song on the Shockwave record, If There Is No Heaven, that’s really about that Flying in a Blue Dream era.

Right — that song has a Police kind of vibe to it, with an Andy Summers guitar feel.

Yeah! I used my original ‘84 Roland JC-120 [Jazz Chorus amp], and the choruses were on. We double-tracked them, and then we chorused them again. We’re somewhere between The Cure and Blur. (both laugh)

And when I presented it to the guys, it had my distorted bass playing on there. I said, “This is exactly what it sounds like. This character is having a memory — metaphysical doubts of bad experiences in the ’80s.” I said to Marco, “Just be playful with it. Every song can be different.” And that’s exactly what he played. He gave us his Police version of it. It was really cool. And it needed it, because the song has three sections, and there isn’t a bridge on it. There’s a verse, and then three choruses. So he could be a little playful with it, but he had to keep the velocity going.

We live in a streaming universe now. How do you feel about that?

My thought is just… share. Share as a musician. The things I worry about as a current entertainer in the business have almost no connection with what the kid at home needs to be continually inspired. It’s almost beyond me to know what they’re looking at and what they’re listening to. It might be the fact that they go, “Wow, look at those high tops he’s wearing! He’s playing that thing on the neck pickup, and he doesn’t seem to be caring about anything! It’s like nothing he’s ever played on any record before!” They study every little thing, and they take it in in such a different way than the way I’m giving it.

“No matter what happens, there’s always some new workaround for the person who’s supposed to pay up.”

Sometimes I think, if we had a cassette of Beethoven working on Moonlight Sonata, we wouldn’t care how it was recorded. You’d just be all over that thing. It’s like listening to recordings of Bird [legendary jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker] — we don’t not listen to it because of the fidelity. We go, “Oh my God, you’ve got a recording of Bird, playing that solo!” And if someone said, “Hey look, I’ve got an old film of Jimi Hendrix being asked some questions, just playing a guitar through any old amp.” I’d be like, “Please, can I hear it? I don’t care!”

At the same time, we are dedicated to delivering the best-sounding product, and we’re not exactly sure where technology is going. We don’t know what’s happening tomorrow, but John and I have done everything with the entire catalog to bring it up to the highest resolution with the most amount of dynamics. So if the technology of streaming advances to where it’s going to be 96k, we’re ready.

Have you dealt with either Pono or Tidal at all?

I signed up with Tidal early on. I dialed it in and went, “I wonder if I’m on Tidal? Oh look, they have a bio!” — and it was the funniest thing. It was a very poor attempt. It wasn’t even copied from Wikipedia; it was just a very bad bio. And they called every record Surfing With the Alien. Can you imagine? “And then, in 1995, he released Surfing With the Alien…” I’m looking at it, going, “I’ve never even seen a cluster-typo like that!” [The aforementioned Surfing With the Alien was released in 1987.]

I wrote them an email: “I love your service. It sounds really good. Hope when it finally launches, it’s great.” This is still when they’re gathering their preview customers, before the big launch. “By the way, it’s me, and you guys should really look at my bio, because it’s really messed up. If you need any info, let me know.”

A couple of weeks go by, and I don’t hear anything. I write them another email. I got a response: “Our tech department is working really hard to blah blah blah.” Finally, after a few months, I was like, “Really, guys?” They had music up — and it was OK. It was good, but it didn’t make me want to never listen to my iTunes again.

It just bothered me that they were saying, “Hey, we’re all this,” and at the same time, they couldn’t fix this teeny little thing. I’m thinking, if you can’t even handle this small detail, what are you really doing with the music?

That had to be really frustrating. How often in your career did you feel you had to compromise what you wanted to hear on the final product?

All the time — especially when your record was coming out on cassette. (both laugh)

Every new technology, the people pushing it say, “This is going to solve that inequity, and make it sound better. And, at the same time, it’s good for the artist.” But no matter what happens, there’s always some new workaround for the person who’s supposed to pay up. (laughs)