All Barry Palmer’s son Declan wanted to do was share a moment from a live concert with his dad. But he didn’t just want your run-of-the-mill iPhone footage; he wanted great video. He wanted high quality sound – he wanted it to be like his dad was actually there, experiencing the concert. The lights, the screaming, the musicians faces, the whole package.

“Having struggled to share even half decent mobile phone footage of the concert, Declan imagined an app that would allow sharing HD quality videos in real time,” explains Palmer, an indie label music executive who is the CEO and co-founder (along with Liza Boston) of a service that aims to do exactly that: Soundhalo. Palmer employs an in-house production team that captures professional quality sound and video from concerts and provides them in a shareable format to fans.

Soundhalo is trying to create a whole new catalog of unique, live experiences.

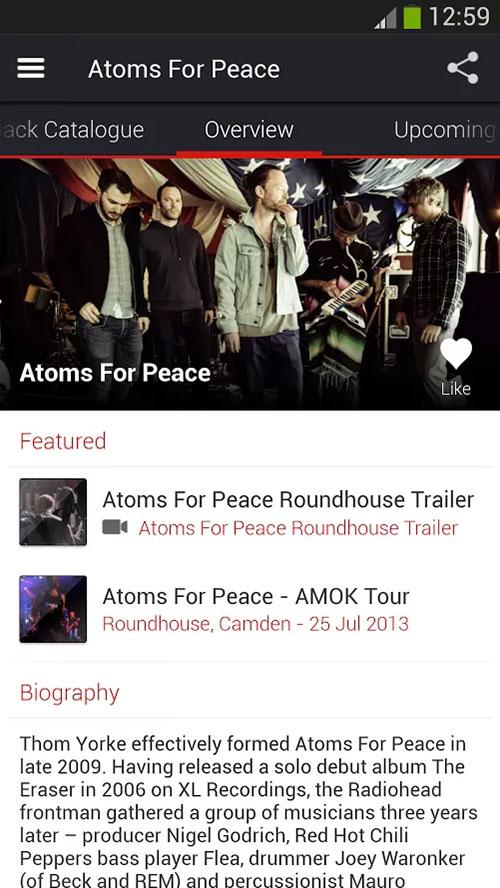

This was followed by a rather surprising twist when Yorke and Atoms for Peace announced a partnership with Soundhalo. While Soundhalo says the deal was in the works before Yorke’s Spotify tirade, the announcement did make Yorke’s actions seem pretty PR stunt-like. So, what is it about Palmer’s digital music service that satisfies a streaming skeptic like Yorke?

The main thing is the most obvious one: there’s no streaming. On Soundhalo, you pay for what you consume – around $1.60 per song or $16 for an entire concert – as opposed to a Spotify-style payment plan that gives you all you can eat, commercial free, for a flat monthly fee. Also, Soundhalo isn’t trying to license every track ever recorded the way Spotify does; it’s trying to create a whole new catalog of unique, live experiences. Soundhalo’s production team records video and audio from a concert that is then mixed and mastered by their “world class mastering engineers.” Then, this content is made available for users to download online almost immediately after the concert is over – as Soundhalo tells it, “just moments after the last note rings out on stage.”

Once you’ve purchased Soundhalo songs, they’re yours to store and sync however you want (they offer cloud storage if you don’t want to lose space by downloading), and the content is all shareable. You can Facebook it, tweet a link, whatever – you can even email the file itself to a friend.

Clearly, Spotify – or Rdio, iTunes, Google Music, whatever – Soundhalo is not. While “traditional” digital music services provide some live music, it’s limited; selection is limited by what the record labels have in their catalogs (and which of those the services can get rights to), and the offering itself is limited to sound and sound alone. Soundhalo looks to create the next best thing to attending a concert yourself – not just hearing a concert but seeing it, too, all in the highest quality format possible.

It’s difficult to know how big a draw the live music gambit it, since none of the established services provide metrics on how popular their live offerings are. But there are some interesting things we do know: For starters, while album sales have dropped thanks to the digital music evolution, there’s been an increased demand for concerts. You could argue that, as our access to music increases, our interest in paying for the real deal – the live concert – increases, too.

Consumer interest in only one part of the equation; there’s also consumer behavior

In the ultimate irony, research conducted in part by Spoitfy determined that live music events are leading to increased illegal downloads. “Our analysis uncovered some examples of torrents spiking immediately after festival performances,” says Spotify. “Festivals increase demand for artists’ music, [that] festival-goers mainly sample through unauthorized channels.”

But consumer interest is only one part of the equation; there’s also consumer behavior. The way Palmer talks about it, you’d think every concertgoer experiences the same frustrations as his son. “Put the phone down,” Palmer recently said about the tendency to self-document concerts. “We are on the cutting edge of the future. [Soundhalo] is about live videos straight from the stage direct to your smartphone.”

Yorke’s Atoms For Peace and Radiohead collaborator Nigel Godrich, for one, agrees: “Part of the reason Soundhalo was interesting to me was that I found myself wondering why, whenever you go to a gig, the next day there are a million shaky, horrible sounding YouTube videos already online,” he said in a release.

But this is where Soundhalo starts to sound potentially out of step with its own potential customers. The videos Godrich complains about are all over the internet because, by all accounts, we – the listeners – want them there. Apps focusing on documenting the live event and specifically the concert experience are coming out of the woodwork, and don’t appear to be going anywhere. Instagram, Vine, Viddy, they are a staple at every concert; they’re the reason for all those lit up screens thrust into the air throughout entire performances. They exploit one of the truest things we know people want to do with social media: Brag. Brag about our music choices, the fact we’re at a live event and an interesting place, that we’re experiencing something unique. (Much to Beyonce’s dismay.)

When Soundhalo is described as a “sharing” app, this isn’t sharing the way many people currently think of it, as it relates to their own concert-going experiences. Your friends aren’t recording and sharing the event with you, Soundhalo – and the artists it’s working with – is. And while you can share what they’ve created with your social circle, it’s not something you made or experienced in the narrative sense that drives so much of what we post to our various social channels. Does cutting out the “I was here and I did this” element in favor of super high quality sound and video sound awesome or awful to you,? Soundhalo needs the answer to be the former.

Of course, before it ever gets an answer to that question, there’s lots to do. The app is still in beta and Soundhalo isn’t releasing details on the other artists it’s working with or how it intends to scale up what sounds like a pretty expensive production model to capture anything beyond a tiny number of concerts on any given day or week. Whatever happens, there’s about to be a whole new way to consume and share music digitally, which can only benefit us, the fans. Then again, ever since music went digital, hasn’t that always been the case?