One of the most dramatic cosmic events is a supernova, when a massive star runs out of fuel. The star explodes in an enormous burst of energy that can be seen even in other galaxies. We know essentially when these supernovae happen, but we aren’t able to predict exactly when any given star will go supernova. Now, though, a team of astronomers has come up with an “early warning system” for stars approaching this critical point.

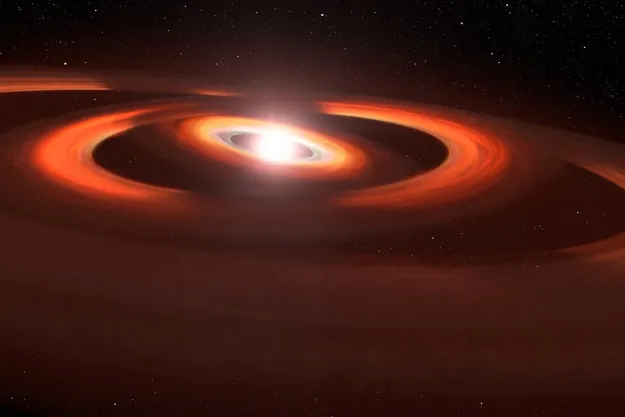

The astronomers from Liverpool John Moores University and the University of Montpellier simulated the development of a group of pre-supernova stars called red supergiants, which are some of the largest stars (though not necessarily the most massive). They include our famous neighbor Betelgeuse. These stars used to be massive stars around eight to 20 times the mass of the sun, but as their fuel runs out, they switch from fusing hydrogen to fusing helium, and they puff up to a larger size while cooling down.

The researchers found that these red supergiant stars become suddenly much fainter in their last few months of life. Their brightness drops by as much as a hundred times as they produce dusty material that obscures the light they give off, making them appear fainter. This dropping brightness will be a clue to an impending supernova.

“The dense material almost completely obscures the star, making it 100 times fainter in the visible part of the spectrum. This means that, the day before the star explodes, you likely wouldn’t be able to see it was there,” lead author Benjamin Davies of Liverpool John Moores University explained in a statement. “Until now, we’ve only been able to get detailed observations of supernovae hours after they’ve already happened. With this early-warning system, we can get ready to observe them in real time, to point the world’s best telescopes at the precursor stars, and watch them getting literally ripped apart in front of our eyes.”

The research is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Editors' Recommendations

- See the stunning Vela supernova remnant in exquisite detail in expansive image

- Hubble captures an exceptionally luminous supernova site

- Astronomers spot rare star system with six planets in geometric formation

- Astronomers spot an exoplanet creating spiral arms around its star

- Tatooine-like exoplanet orbits two stars in rare astronomical discovery