“Right now, smartwatches are mostly glorified fitness trackers with a touch screen,” Chris Harrison, assistant professor of Human-Computer Interaction at Carnegie Mellon, told Digital Trends. “I don’t think we’ve real seen the true emergence of what a smartwatch can be. Smartphones opened up whole new domains for us, like Uber and Yelp and various other apps, which we didn’t have before. Smartwatches haven’t had that moment yet. Right now, they’re still glorified digital watches.”

“It’s recasting the role of the smartwatch.

Harrison’s not trolling the efforts of smartwatch companies, though. Working with a team of other researchers from the university’s Human-Computer Interaction Institute, his lab has been busy exploring how wearable devices can better live up to the “next big thing” label they’ve been assigned.

And you know what? After years of hard work, they may have just cracked it!

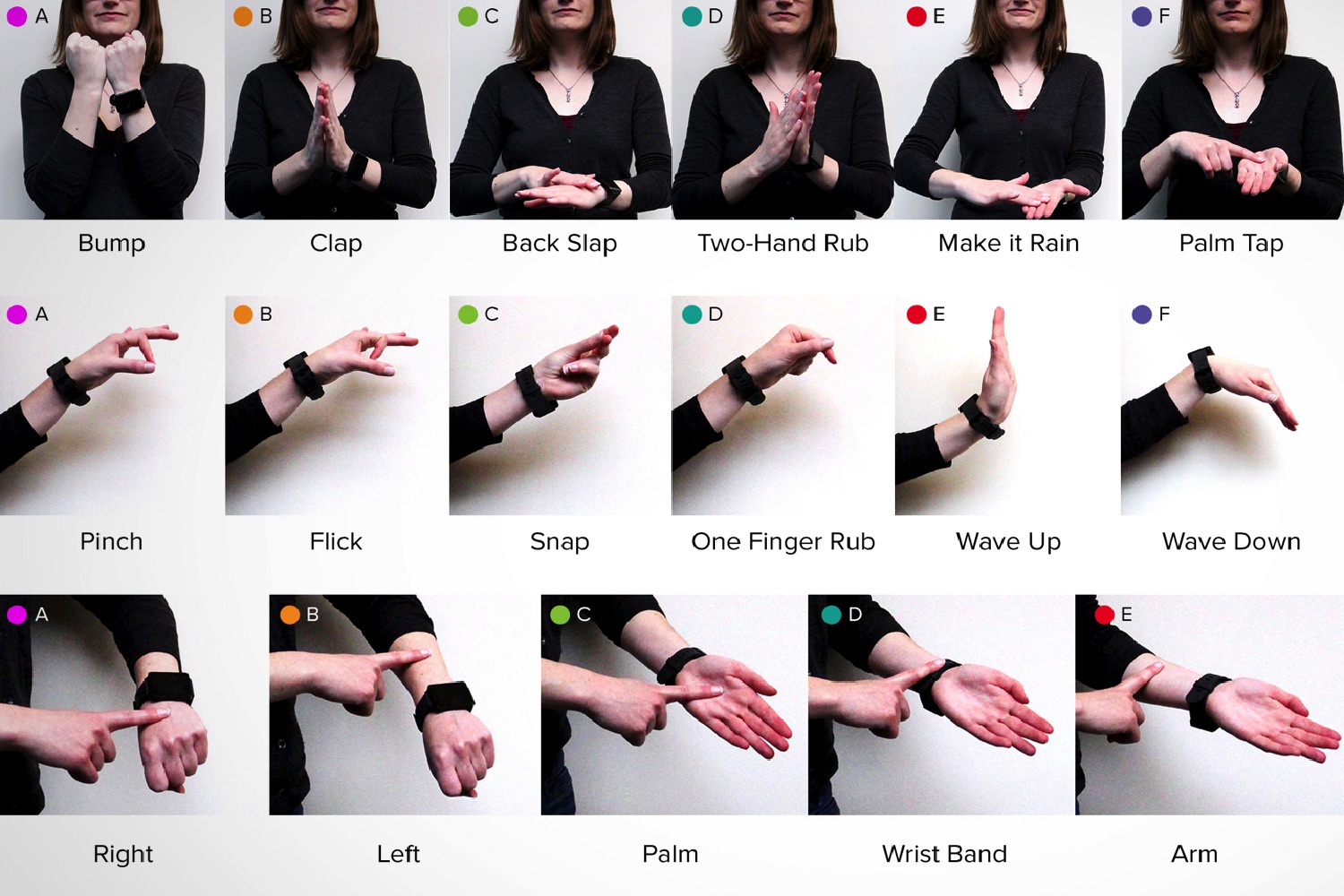

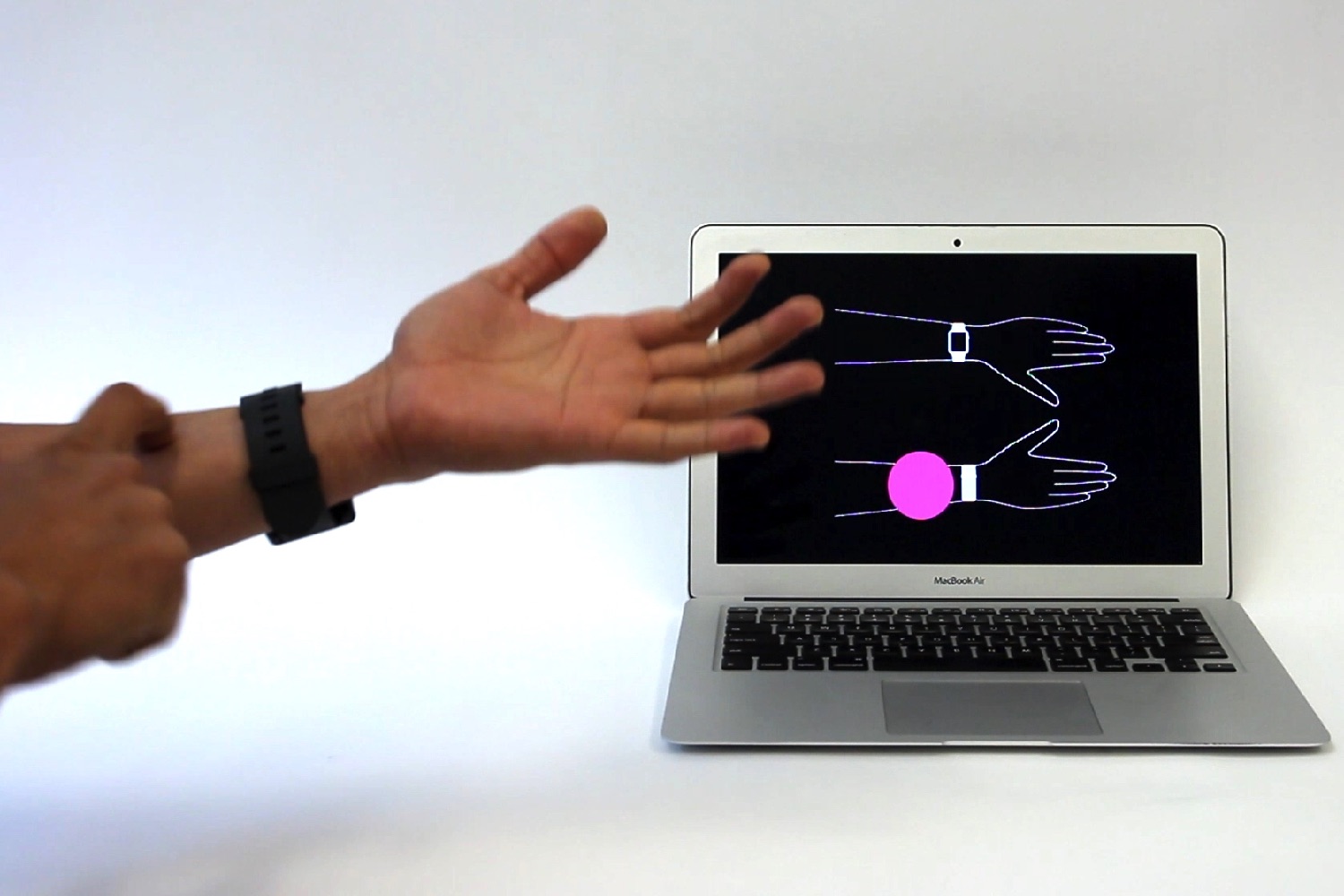

The solution they have come up with is a project called ViBand, which repurposes the built-in accelerometer found in smartwatches and uses it to detect various gestures made by the user. Oh, and you don’t have to touch the screen for it to work, either.This is achieved through the use of a custom smartwatch kernel that boosts the accelerometer’s sampling rate up from 100 Hertz to 4 kilohertz (a 4000 percent increase). Doing so allows the accelerometers to detect tiny vibrations that travel through the wearer’s arm, which opens up a massive range of potential applications.

“Your hand is the chief way that you manipulate the world around you,” Professor Harrison continued. “You shake hands with people, type on keyboards, put coffee in your mouth, touch objects, and much more. We wanted to know if we could take all of this and use it to augment the user experience by capturing unique information about the hand. It’s recasting the role of the smartwatch.”

Given that smartwatch screens are never going to be large enough for complex hand-based input, it’s a clever concept because it ditches an insubstantial input (the tiny smartwatch screen) for one that’s got a whole lot more surface area — namely the human body.

“This has enormous possibilities in simplifying people’s lives.”

“We didn’t just want to do hand gestures, but also to put a virtual button on the skin,” Harrison said. “For example, if you tap your elbow it should be possible for that to trigger a certain type of functionality.”

This all well and good, but the really impressive part of ViBand is still to come. That’s the fact that it doesn’t just recognize what the hand is doing in isolation, but can also work out when a user is touching a particular object and trigger an action accordingly.

“This has enormous possibilities in simplifying people’s lives,” Harrison said. “Right now, if you have a smart home and you want to modify the color or brightness of a Philips Hue light, for example, you have to pull out your phone, go into the app, and change the settings there. If a smartwatch knows what you touch, on the other hand, you can have a scenario where just touching a light switch will open up the correct app. It’s all about context sensing, and it’s a magic user experience that only a smartwatch can really pull off. It can always be two steps ahead of you.”

At present, the ViBand project is still described as an “exploratory research project,” meaning that your best shot of using it is to enroll as a computer science major at Carnegie Mellon. However, since every great user interface starts out as a piece of R&D, there’s nothing to say this isn’t how all smartwatches will work one day.

There has certainly been plenty of interest in the project. When it was presented at last week’s Association for Computing Machinery’s User Interface Software and Technology (ACM UIST) Symposium in Tokyo, it won a well-deserved “Best Paper” award. From here, it’s just about getting the tech giants to see the light — or, rather, the smart gestures.

Hey, if all smartwatches end up working like this, remember that you read about it at Digital Trends first!