Saturn is famed for its beautiful rings, but these rings are something of a puzzle to astronomers. Originally, it was thought that they must have formed around the same time as the planet, over 4 billion years ago. But data from the Cassini spacecraft suggested the rings might be much younger than that, forming less than 100 million years ago. Now, a new study suggests that the rings could have been formed from a long-lost moon, explaining several of Saturn’s peculiarities.

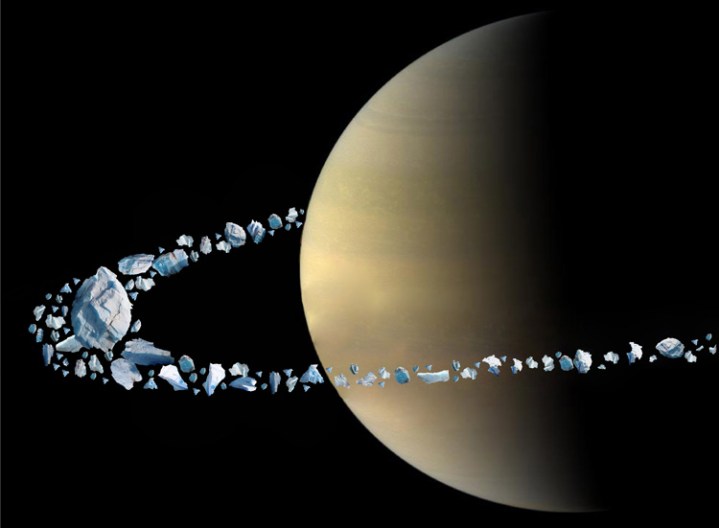

Saturn rotates with a tilt of 27 degrees, slightly off the plane at which it orbits the sun, and its rings are tilted too. Recently published research proposes that both of these factors can be explained by a former moon, named Chrysalis, which came close to the planet and was torn apart. Most of the moon was absorbed by the planet, but the rest of it created the stunning rings.

This can explain the planet’s tilt too. The long-held theory was that Saturn was tilted due to the gravitational forces of Neptune, but the new model suggests that while this might have been the case long ago, today Saturn is no longer in resonance with Neptune. It could have been the movements of this since-destroyed moon that caused the planets to fall out of resonance.

“The tilt is too large to be a result of known formation processes in a protoplanetary disk or from later, large collisions,” lead researcher Jack Wisdom of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology said in a statement. “A variety of explanations have been offered, but none is totally convincing. The cool thing is that the previously unexplained young age of the rings is naturally explained in our scenario.”

The existence of the Chrysalis moon, thought to be about the size of Iapetus, Saturn’s third-largest moon, can therefore explain both why the rings are so young and why the planet tilts the way it does.

“Just like a butterfly’s chrysalis, this satellite was long dormant and suddenly became active, and the rings emerged,” said Wisdom.

The research is published in the journal Science.

Editors' Recommendations

- NASA gives green light to mission to send car-sized drone to Saturn moon

- Lunar lander is on its side on the moon’s surface

- Saturn’s tiny moon, Mimas, hosts an unexpected ocean beneath an icy shell

- How to watch the Quadrantid meteor shower hit its peak tonight

- Hubble snaps an image of dark spokes in Saturn’s rings