Astronomers from the German Aerospace Center Institute of Planetary Research have discovered a terrifying planet: Smaller than Earth and so close to its star that it completes an orbit in just eight hours. Its host star, located relatively nearby at 31 light-years’ distance, is a red dwarf which is smaller and cooler than our sun, but even so, the planet is so close that its surface temperature could reach up to 2,700 degrees Fahrenheit. And the planet is bombarded with radiation that is over 500 times stronger than the radiation on Earth.

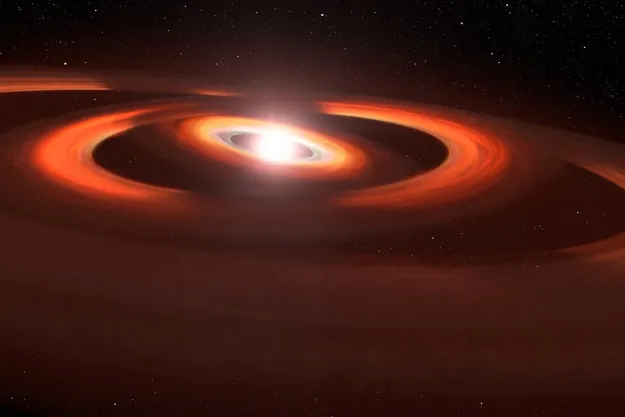

The planet, called GJ 367 b, is smaller than most exoplanets discovered so far, which tend to be comparable in size to Jupiter. It has just half the mass of Earth but is slightly larger than Mars with a diameter of 5,500 miles. It was discovered using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), a space-based planet-hunter that detects planets using the transit method, in which it observes the light from distant stars to look for dips in brightness caused by a planet moving between the star and Earth.

After its discovery using TESS, GJ 367 b was further investigated using the European Southern Observatory’s 3.6m Telescope, a ground-based telescope that uses a different method to more precisely determine its radius and mass.

“From the precise determination of its radius and mass, GJ 367 b is classified as a rocky planet,” explained lead researcher Kristine Lam. “It seems to have similarities to Mercury. This places it among the sub-Earth-sized terrestrial planets and brings research one step forward in the search for a ‘second Earth’.”

However, despite its similarities to Earth, you wouldn’t want to move to GJ 367 b. Its surface temperature is so hot it could almost vaporize iron, and the researchers think that the planet may have lost its entire outer layer, called the outer mantle.

But studying the planet could help astronomers learn more about how planets and planetary systems form, which could help us understand more about the development of our own planet and solar system.

When it comes to planets orbiting this close to their stars, called ultra-short period (USP) planets, “We already know a few of these, but their origins are currently unknown,” said Lam. “By measuring the precise fundamental properties of the USP planet, we can get a glimpse of the system’s formation and evolution history.”

The research is published in the journal Science.

Editors' Recommendations

- First indications of a rare, rainbow ‘glory effect’ on hellish exoplanet

- Relive SpaceX’s first booster landing exactly 8 years ago

- James Webb finds that rocky planets could form in extreme radiation environment

- Watch a video of an exoplanet orbiting its star — made from 17 years of observations

- Webb spots water vapor in a planet-forming disk