In the last decade, telescopes have discovered thousands of planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets, giving us a tantalizing glimpse into possible worlds beyond our own. But the next generation of telescopes will be able to discover even more, like the upcoming NASA Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope which could discover tens of thousands of exoplanets.

To find new planet candidates, Roman will use a method called microlensing. This works by looking at a large number of stars and watching for a time when one star passes in front of another from our perspective on Earth. When this happens, the gravity of the foreground star bends the light being given off by the background star, resulting in a small fluctuation in brightness. This allows scientists to learn about the foreground star, including whether it might host planets.

The challenge with this method is that it is extremely rare for two stars to line up just so. In order to find two stars lining up, the telescope has to observe millions of stars to increase the chances of seeing one pass in front of another.

“Microlensing events are rare and occur quickly, so you need to look at a lot of stars repeatedly and precisely measure brightness changes to detect them,” astrophysicist Benjamin Montet, a Scientia Lecturer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, said in a statement.

This is handy in several ways, as such observations also enable a different type of exoplanet detection using the transit method. “Those are exactly the same things you need to do to find transiting planets, so by creating a robust microlensing survey, Roman will produce a nice transit survey as well,” Montet said.

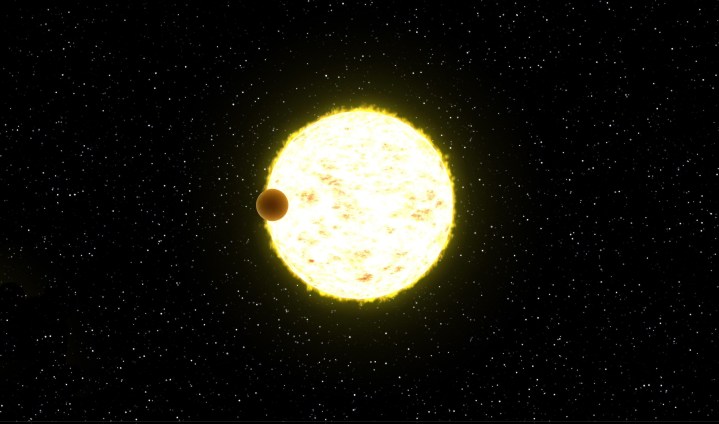

The transit method looks for dips in the brightness of stars caused when a planet passes between the star and us. This provides an additional method for discovering even more exoplanets from the same data. This method is best for finding planets close to their stars, while microlensing is best for finding planets far from their stars.

“The fact that we’ll be able to detect thousands of transiting planets just by looking at microlensing data that’s already been taken is exciting,” said study co-author Jennifer Yee, an astrophysicist at the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “It’s free science.”

A research paper from Montet estimated that using microlensing, Roman could detect as many as 100,000 planets, and it may discover even more using the transit method as well. The telescope is scheduled to launch in the mid-2020s.

Editors' Recommendations

- Hubble discovers over 1,000 new asteroids thanks to photobombing

- Small exoplanet could be hot and steamy according to Hubble

- SpaceX has set a new date for Axiom-3 crewed rocket launch

- How astronomers used James Webb to detect methane in the atmosphere of an exoplanet

- James Webb investigates a super puffy exoplanet where it rains sand