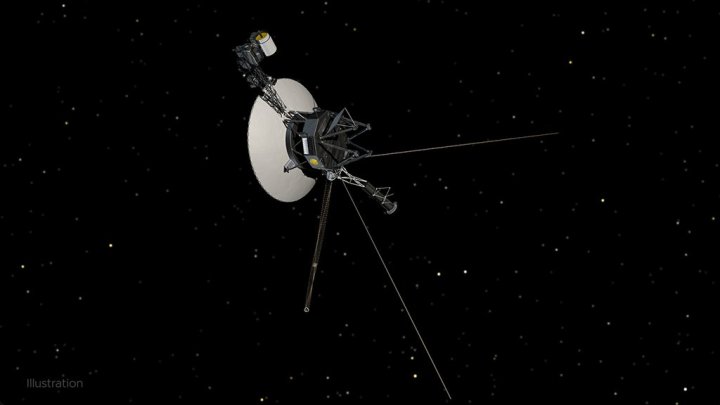

In the 1970s, two spacecraft were designed and built for the wildly ambitious mission to study the outer reaches of the solar system. More than 40 years later, the two Voyager spacecraft are, incredibly enough, still functioning and transmitting data, even as they have left most of the solar system behind and headed out into interstellar space. The two craft have survived various glitches and problems, however, a recent issue with Voyager 1 has engineers at NASA scratching their heads.

Voyager 1’s altitude articulation and control system (AACS) is sending back some strange readings, and engineers are puzzled as the craft is still operating normally. The AACS is responsible for keeping Voyager in the right orientation and making sure that its antenna is pointing toward Earth so that the spacecraft can transmit data. But now, the AACS is sending back data that doesn’t make any sense — the data looks like it could be scrambled, for example, or suggests that the system is in an impossible state — even though the antenna is still pointing the right way and transmitting just fine.

The good news is that the spacecraft is still transmitting, and the issue has not forced the craft to go into safe mode. The signal continues to come through as strong as it was before, so engineers are confident that the antenna hasn’t shifted. But why the AACS is misbehaving in this way remains a mystery.

“A mystery like this is sort of par for the course at this stage of the Voyager mission,” said the project manager for both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, Suzanne Dodd of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in a statement. “The spacecraft are both almost 45 years old, which is far beyond what the mission planners anticipated. We’re also in interstellar space – a high-radiation environment that no spacecraft have flown in before. So there are some big challenges for the engineering team. But I think if there’s a way to solve this issue with the AACS, our team will find it.”

To try to figure out what the issue is, the team will keep monitoring the messages sent by the spacecraft to try and see if the problem is with the AACS itself, or with one of the systems that transmit the data. But this will take a while, as Voyager 1 is so far away — at 14.5 billion miles (23.3 billion kilometers) from Earth currently — that it takes a long time for the signals to travel that distance. It currently takes almost two days to send a signal and receive a response.

The team may or may not be able to find out what’s causing the issue, but for now, they are happy that the spacecraft is still operating and that the AACS issue is a puzzle but not an immediate threat to the craft’s well-being.

Editors' Recommendations

- Voyager 1 spacecraft is still alive and sending signals to Earth

- Meet NASA’s trio of mini moon rovers set to launch next year

- Asteroid impacted by spacecraft is reshaped like an M&M ‘with a bite taken out’

- Watch Sierra Space blow up its LIFE habitat in dramatic pressure test

- NASA confirms burn-up date for failed Peregrine spacecraft