Astronomers have discovered a “forbidden” planet that appears to be far larger than should be possible given its circumstances. A team of researchers investigated a candidate exoplanet called TOI 5205b, first identified by NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), and not only confirmed that the planet was there but also discovered that it has some baffling characteristics.

The exoplanet orbits a type of star called an M dwarf or red dwarf. These are the most common type of stars in our galaxy and are small and cool, typically being around half as hot as our sun.

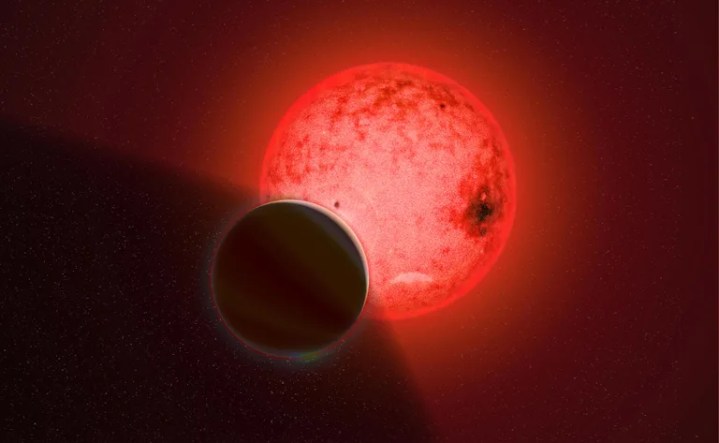

While it’s common to find exoplanets orbiting red dwarfs, it’s rare to find gas giants orbiting them. And in the case of the recent discovery, the gas giant exoplanet was found orbiting a low-mass M dwarf, which is unheard of. The planet is very large in comparison to its star and blocks out around 7% of the star’s light when passing in front of it.

“The host star, TOI-5205, is just about four times the size of Jupiter, yet it has somehow managed to form a Jupiter-sized planet, which is quite surprising!” said lead researcher Shubham Kanodia of the Carnegie Institution for Science in a statement.

The reason the finding is surprising is due to the way that planets form. Planets are thought to form from disks of gas and dust around stars called protoplanetary disks. But models of gas giant formation suggest that these need a core of rocky material to come together first before gas gets quickly swept up to form the planet — and that doesn’t seem to be possible in this case.

Even if all of the material in the disk around this star came together to form one planet, it still wouldn’t be enough to form a gas giant of this size — there would need to be at least five times as much material to form something this large.

“TOI-5205b’s existence stretches what we know about the disks in which these planets are born,” Kanodia said. “In the beginning, if there isn’t enough rocky material in the disk to form the initial core, then one cannot form a gas giant planet. And at the end, if the disk evaporates away before the massive core is formed, then one cannot form a gas giant planet.

“And yet TOI-5205b formed despite these guardrails. Based on our nominal current understanding of planet formation, TOI-5205b should not exist; it is a ‘forbidden’ planet.”

As for how this planet came to be, it could be that there is a lot more dust in these disks than previously thought, or that there are some aspects of planetary formation that we don’t understand yet. To learn more, the researchers suggest that the planet could be investigated using the James Webb Space Telescope — and it makes an enticing prospect because of its large transit.

The research is published in The Astronomical Journal.

Editors' Recommendations

- First indications of a rare, rainbow ‘glory effect’ on hellish exoplanet

- Three tiny new moons spotted orbiting Uranus and Neptune

- Small exoplanet could be hot and steamy according to Hubble

- See the weather patterns on a wild, super hot exoplanet

- Astronomers spot rare star system with six planets in geometric formation