The origin of a mysterious gamma-ray source that has been puzzling astronomers for seven years has been identified thanks to the donated computer power of thousands of volunteers. The Einstein@Home project is a distributed computing project which uses the processing power of volunteers’ computers to solve big puzzles in science, and it has paid dividends in the form of this new discovery.

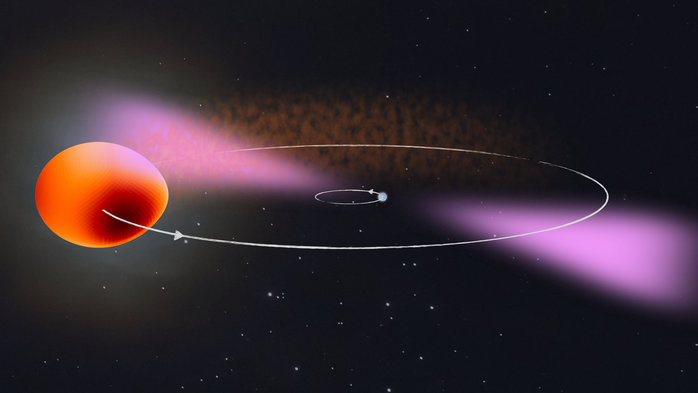

In 2014, object PSR J2039−5617 was discovered giving off X-rays, gamma-rays, and light. Researchers thought that this object was a neutron star and a smaller star in a binary system, but they needed more data to be sure.

“It had been suspected for years that there is a pulsar, a rapidly rotating neutron star, at the heart of the source we now know as PSR J2039−5617,” said Lars Nieder, a Ph.D. student at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics and co-author of the study, in a statement. “But it was only possible to lift the veil and discover the gamma-ray pulsations with the computing power donated by tens of thousands of volunteers to Einstein@Home.”

The researchers began by imaging the object with optical telescopes and observed that the binary star had a 5.5-hour orbital period. They still needed more data to know about the gamma-rays being given off by the object though. That’s when they turned to Einstein@Home.

Using the spare processing cycles of the CPUs and GPUs of the computers belonging to tens of thousands of volunteers, the researchers could search through 11 years of data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope. They looked for periodic pulses of gamma-ray photons and were able to pin down regular pulses from the neutron star.

According to the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics, where the research was performed, the search would have taken 500 years to complete on a single computer core. But thanks to the Einstein@Home volunteers, they were able to complete the search in two months.

Now the team wants to perform more searchers for gamma-ray sources using the distributed computing network. “We know dozens of similar gamma-ray sources found by the Fermi Space Telescope, for which the true identity is still unclear,” said Professor. Dr. Bruce Allen, director at the Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics and founder of Einstein@Home. “Many might be pulsars hidden in binary systems and we will continue to chase after them with Einstein@Home.”

Editors' Recommendations

- Dramatic luminous kilonova is 10 times brighter than predicted

- NASA Chandra images highlight the beauty of the universe in X-ray wavelength

- Hubble observes mammoth gamma-ray burst with highest-ever energy levels