Scientists have found the first black hole ever to get its picture taken, known as M87, is rotating and changing over time.

According to a new study published in The Astrophysical Journal, the black hole’s ring of material around it and its crescent-like shadow feature haven’t changed in size over the period of observation, but its brightness, and where it is bright, have drastically changed. The shadow appears to be “wobbling” over time.

“Because the flow of matter is turbulent, the crescent appears to wobble with time,” said Maciek Wielgus of the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and lead author of the paper. “Actually, we see quite a lot of variation there, and not all theoretical models of accretion allow for so much wobbling. What it means is that we can start ruling out some of the models based on the observed source dynamics.”

The study looked at preliminary data of the M87 black hole from 2009 to 2013 and the 2017 images using the Event Horizon Telescope. Scientists found that the ring on the black hole’s right side was brightest in 2013, while the bottom of the ring was the brightest in 2017.

M87’s enormous size (6.5 billion times the mass of our sun) gives scientists an advantage to view these smaller changes over time. The findings released in Wednesday’s study will better help scientists understand phenomena such as relativistic jets and general relativity theory.

The M87 black hole is located in the Messier 87 galaxy, 55 million light-years away, and was captured in an image last year.

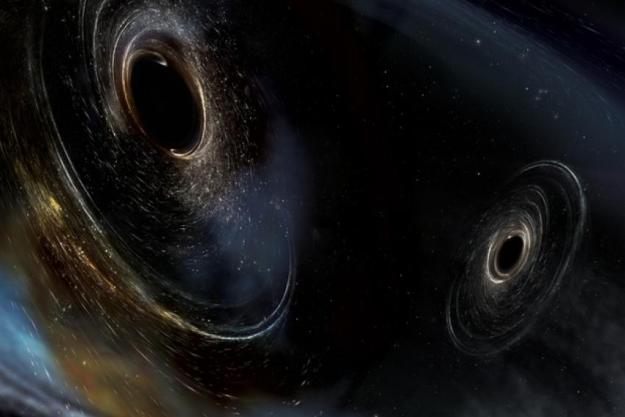

After that historical photo, scientists also discovered that baby black holes “chirp” as they are born, just as Albert Einstein predicted. The pitch of the waves could signal the black hole’s potential mass and spin and the loudest part of this “chirp” indicates the exact moment when the two black holes collided, creating an entirely new black hole.

Editors' Recommendations

- Biggest stellar black hole to date discovered in our galaxy

- Nightmare black hole is the brightest object in the universe

- Juice spacecraft gears up for first ever Earth-moon gravity boost

- This peculiar galaxy has two supermassive black holes at its heart

- Measure twice, laser once. Meet the scientists prodding NASA’s first asteroid sample