The Hubble Constant is one of the most important concepts in astronomy. It describes how fast the universe is expanding, which has implications for the age and future development of the universe.

Many different figures have been presented for the constant over the years, based on different data analyses. A recent estimate based on data from the Hubble Space Telescope found the constant to be in the region of 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec. That means that for every megaparsec of distance (a megaparsec is approximately 3.26 million light-years) that an object is away from you, its velocity would appear to increase by 74 kilometers per second.

Now, a new paper has used a different technique to estimate the constant and found a slightly slower rate of expansion of 67.5 kilometers per second per megaparsec. To find the constant, the team looked at the interactions between gamma rays, which are a highly energetic form of electromagnetic radiation, and the background light fog of the universe, called the extragalactic background light (EBL). As the gamma rays move through the EBL, they are absorbed and attenuated.

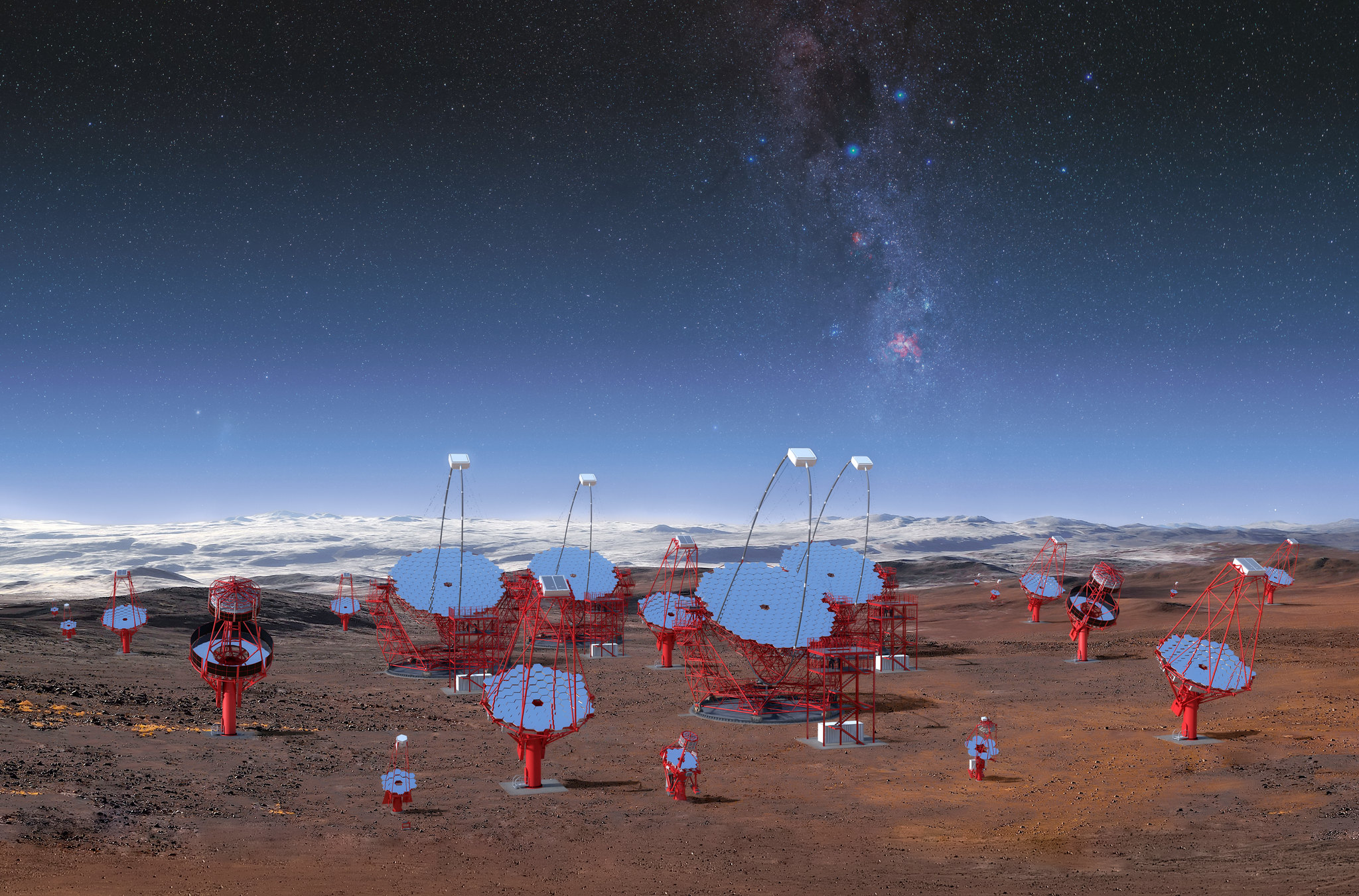

The scientists studied the rate of attenuation to figure out how far the gamma rays had traveled. If they were highly attenuated, they must have traveled further, indicating faster expansion. If they were less attenuated, the expansion must be slower. They collected data using the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope and Imaging Atmospheric Cherenkov Telescopes, like those in the Cherenkov Telescope Array pictured above.

“Cosmology is about understanding the evolution of our universe — how it evolved in the past, what it is doing now and what will happen in the future,” co-author Marco Ajello, an associate professor in the Clemson University department of physics and astronomy, said in a statement. “Our knowledge rests on a number of parameters — including the Hubble Constant — that we strive to measure as precisely as possible. In this paper, our team analyzed data obtained from both orbiting and ground-based telescopes to come up with one of the newest measurements yet of how quickly the universe is expanding.”

The findings are published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Editors' Recommendations

- James Webb researcher reveals how it will investigate the early universe

- See how beautiful the universe looks in the X-ray wavelength

- Hubble solves the mystery of the bizarre disappearing exoplanet

- Hubble’s 30th anniversary image is a stunning depiction of star birth

- The peaceful-looking Umbrella Galaxy has a violent, cannibalistic past