Now that HDTV has been around for a while, prices have dropped substantially, and we tend to take it for granted. But in HDTV’s early years, the price of admission into the ultra-clear, pixel-packed format was super expensive. Still, bulging wallets be damned, consumers were quick to embrace the technology.

Now that HDTV has been around for a while, prices have dropped substantially, and we tend to take it for granted. But in HDTV’s early years, the price of admission into the ultra-clear, pixel-packed format was super expensive. Still, bulging wallets be damned, consumers were quick to embrace the technology.

HD sets were made first made available in 1998, and by 2008, 33 percent of American households owned at least one. Today, Nielsen estimates that 75 percent of homes house an HDTV. Clearly, the technology has spread like wildfire, but it did so – in part – thanks to an initial swell of demand. Consumers wanted this from the beginning, as brighter, sharper images proved seductive enough to spur mass adoption.

So, in this digital age – an age where everything is moving forwards at breakneck speed – why has the sound quality of our personal audio devices stagnated? Or worse still: Why has it been thrown into reverse?

The iPod’s Domination

According to CNN, 75 percent of Americans aged 18-34 own an mp3 player, and 56 percent of those aged 35-46 do. That’s what you call mass adoption. The mp3 player has become a ubiquitous device and, clearly, one brand is head-and-shoulders above the rest in this arena. In fact, Apple’s iPod has such a stranglehold on the industry, its name has supplanted those of other brands’ digital music players. Of course, that makes perfect sense when you consider that – according to Forbes – Apple has retained a 70+ percent share of the MP3 player market for nine years running. Props to Apple for dominating its competition to that degree, but there is one aspect of that stat that sticks in our craw: The iPod’s sound quality is…meh.

Wow this sounds … OK

Let’s be clear, compared to its direct competitors (those similarly priced and featured) its audio stands up fairly well. There are, however, plenty of higher-end options out there that boast a superior sound signature. iRiver’s AK100 is a prime example. Ignore the fact that its name pays homage to Apple, and consider the fact that its audio is leaps and bounds better than the iPod’s. What you can’t ignore, however, is its price tag, which weighs-in at $750. Still, Apple’s 5th generation iPod Touch retails for $400, and the AK100’s sound quality is certainly twice as good. And if you were to tack on something like Red Wine Audio’s iMod to enhance an iOS device’s capabilities, you’re right in the same ballpark.

So what makes your iProduct sound sub-par? Well, there are several answers to that question, each of them complicated. The first is that it won’t support truly high-quality headphones. Why? High-end headphones need power – lots of it – and iPods and iPhones lack a headphone amp capable of pumping out the requisite juice. Higher-quality headphones can also have higher impedance, which is basically their ability to resist electricity. iPods generally have trouble handling anything over 40 Ohms, while many pricey pairs of cans sport an impedance of 70 Ohms or more.

The second issue is that the iPod is not outfitted with what you would call a “premium” DAC (digital to analog converter), which plays a large role in how good any digital audio ends up sounding when played back.

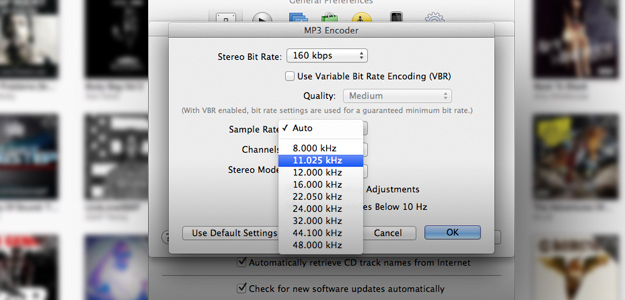

Finally, the iPod is incapable of playing back audio at anything better than CD quality. In fact, most files you’re hearing on the device don’t even sound that good. To be fair, however, it’s not really the iPod’s fault. Here’s where we deal with the issue of formats

Formats

The digital music revolution made life easier in myriad ways. Suddenly music was simpler to acquire, share, organize, and play, but there were drawbacks, too. When a song is digitized, a lot of information can be lost in translation. Less information = less faithful playback, and the music you love is, at best, diminished, and at worst, ruined. There are plenty of digital file types, each with their own advantages and drawbacks, but by far the most ubiquitous is the mp3 file. MP3s are created via “lossy compression,” a form of compression that deliberately discards bits of data. To make a long story short, MP3s simply don’t sound as good as CDs.

Let’s digress for a second and think about that. Imagine TV manufacturers and broadcasters had come to their customers with a proposition: ‘Instead of giving you clearer, higher-quality TV, we’re going to make TV highly portable and broadcasting content much easier to access – but we’re going to do so via a new format that will degrade picture quality.’ What do you think consumers would have said? It would have been a tough sell to say the least. So why is audio any different? Is it because we have trouble confirming what we can’t see? Or is convenience just paramount in the audio world?

In any case, MP3s are built around making sacrifices. If you’re looking for lossless audio, the easiest method is to use a program that will let you “rip” a CD. The problem is that feels like running in place. Are we supposed to be impressed that we can achieve CD-quality in 2013? Because we’re certainly not. After all, just as information is lost in the transfer from CD to MP3, information is lost in the transfer from studio mastering to CD.

There are, however, alternatives. At this point, most of them are little-known, but digital files such as FLAC files, actually reproduce the exact information stream originally recorded in studio. At 24 bits/192kHz (two channels of 192,000 samples per second, 24 bits per sample), the FLAC codec gives us what you’d think we’d all be looking for – an exact reproduction of the source material.

Yet nobody cares.

Or at least nobody seems to. Personal music devices that employ the format are niche devices, generally ignored by all but audiophiles, while the rest of the populous bops their head to lossy, degraded, skeletons of the tracks they love. High-end personal audio offerings are expensive, sure, but they’re certainly not prohibitive. There are plenty of consumers out there snapping up $1,000 TVs, yet we scoff at a $750 digital music player. We haven’t worked out why yet, but we can’t help but feel there should be more folks out there listening to music the way it was meant to be heard