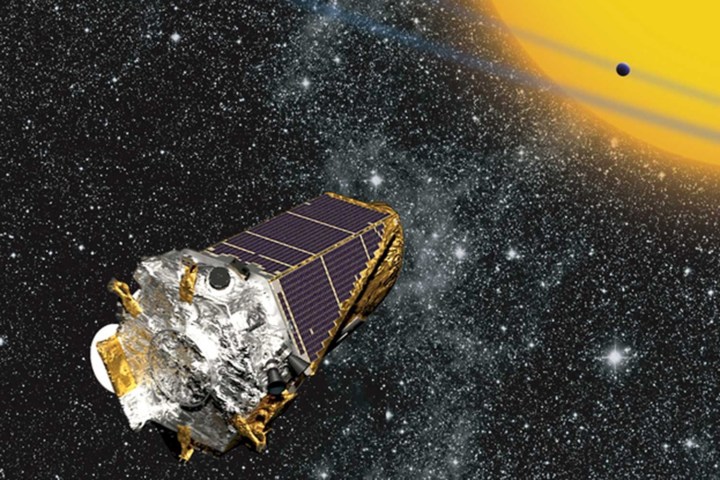

Oddly enough, the finding was facilitated by technical trouble with the telescope, which trails Earth’s orbit, peering into space in search of Earth-sized exoplanets near habitable zones.

“Kepler’s malfunction necessitated a change in mission strategy, from a long-term survey of a small patch of sky to a set of shorter-duration observations of a much wider fraction of the sky,” the paper’s lead author, Ian Crossfield, told Digital Trends. “This new K2 observing strategy means that we find planets with shorter ‘years,’ but the planets we find tend to orbit stars closer to the Earth.” These target stars are relatively bright, enabling more refined study and understanding of their systems.

The four promising exoplanets orbit K2-72, a cool, red, dwarf star 181 light years from Earth that’s about half the size of our sun. The planets themselves are between 20 and 50 percent larger than Earth.

“From studying other planetary systems, we know that these sizes mean that the odds are good that all four of these planets are rocky,” Crossfield said. “Although some of these planets receive roughly the same amount of starlight from their star as Earth does from the Sun, we know nothing about these planets’ atmospheres … and so can’t be sure which of these might be as temperate as the Earth, or which might be inhospitable, infernal greenhouse planets like Venus.”

In order to confirm that the data did indeed depict planets, scientists collected high-resolution images of target stars using an array of telescope around the world. Optical spectroscopy data allowed the astronomers to determine the stars’ properties and infer the properties of the planets in their orbit.

Exciting in its own right, the finding also paves the way for NASA’s future exoplanet hunting missions, including the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite that is set to launch in December 2017 and the James Webb Space Telescope that is scheduled to begin operations in October 2018.

Editors' Recommendations

- Junk from the ISS fell on a house in the U.S., NASA confirms

- See planets being born in new images from the Very Large Telescope

- Small exoplanet could be hot and steamy according to Hubble

- See the weather patterns on a wild, super hot exoplanet

- Astronomers spot rare star system with six planets in geometric formation