“Turing learning has outperformed a traditional machine learning method when it comes to accurately predicting what a swarm of robots do.”

But researchers from the University of Sheffield say they have developed a method that helps artificial systems learn by observing the world around them. It may lay a new foundation for predictive and learning technologies.

Dubbed “Turing learning,” this new method was inspired by the famous Turing test, which was first proposed by the father of computer science, Alan Turing, in 1950.

In the traditional Turing test, a human interrogator converses with two unseen entities, one being human and the other being an artificial intelligence. If the interrogator cannot distinguish the human from the machine, the machine is said to have passed the Turing test.

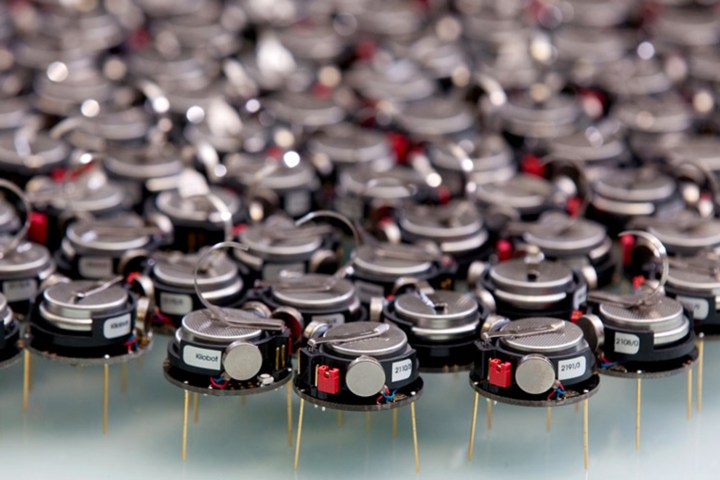

In the Turing learning study, the human interrogator was replaced by an algorithm, the human subject was replaced with a swarm of robots, and a computer simulation attempted to replicate the robots’ movement, just as the Turing test AI attempts to replicate human speech. By analyzing the movement patterns of the swarm and the simulation, the algorithm tried to determine which was which. The algorithm was rewarded for guessing correctly. The simulation was rewarded for fooling the algorithm.

“Turing learning may also be used one day to predict the behavior of humans, no matter whether they are in the real world or the Internet.”

Dr. Roderich Gross and his team used Turing learning to train the algorithm and train the simulation, such that the two learned their tasks in conjunction with each other. In a paper published online at arXiv, they describe how the learning method allowed the systems to make more accurate simulations of the robot swarm through the simple act of observation without needing human input.

“Predicting swarms is particularly challenging, as the motion of each individual within the swarm is different, every time you look at it,” Gross tells Digital Trends. However, “Turing learning has outperformed a traditional machine learning method when it comes to accurately predicting what a swarm of robots do.”

The study observed only robot swarms which, although thought provoking, is of limited practical value. Still, the researchers think Turing learning may offer a new method of prediction and learning for behavior in the natural world and even the world wide web.

“We would like to see whether it can predict what natural swarms do — from colonies of bees to schools of fish,” Gross says. “Turing learning may also be used one day to predict the behavior of humans, no matter whether they are in the real world or the internet.”

Editors' Recommendations

- Apple’s ChatGPT rival may automatically write code for you

- Meta made DALL-E for video, and it’s both creepy and amazing

- Optical illusions could help us build the next generation of AI

- Lambda’s machine learning laptop is a Razer in disguise

- Read the eerily beautiful ‘synthetic scripture’ of an A.I. that thinks it’s God