As computers transform from tools to assistants over the coming years, the learning needs of the technology we use on a daily basis are going to grow exponentially. These services will be more sophisticated and reach much further than today — but they’re going to have to get a lot smarter before they do.

Computer systems, artificial intelligence, and helper robots will need to hit the books on a whole host of topics — human conversation, cultural norms, social etiquette, and more. Today’s scientists are teaching AI the lessons they’ll need to help tomorrow’s users, and the course schedule isn’t what you’d expect.

The first steps toward smarter AI

Last year, within the confines of the Human-Robot Interaction Laboratory at Boston’s Tufts University, a small robot approached the edge of a table. Upon reaching this precipice, the robot noted that the surface it was walking on had come to an end, and told its operator, “Sorry, I cannot do that.”

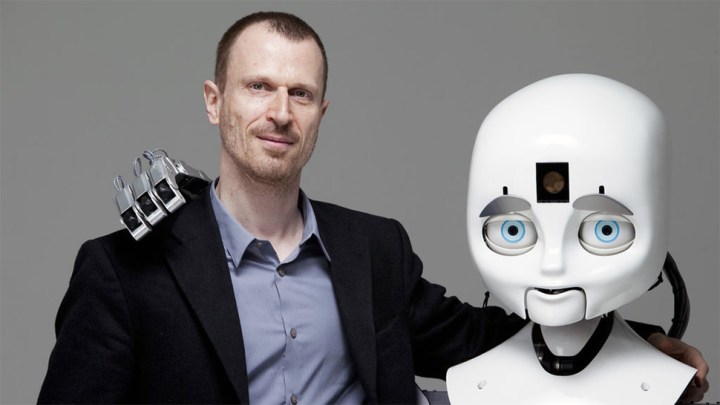

In doing so, the machine confirmed that the work carried out by Matthias Scheutz and Gordon Briggs had been a success. The pair had set out to give their robot the ability to reject a request laid out by a human operator, with their test subject’s tabletop act of self-preservation being a demonstration of the system at work.

Scheutz and Briggs’ project is part of a crucial branch of research into artificial intelligence. Human-robot interaction — sometimes referred to as HRI — is an essential element of our continued work toward the practical application of AI. It’s easy to forget, with robots still largely a hypothetical concern for most, that these machines will one day have to integrate with the humans that they’re intended to assist.

Teaching a robot how to walk is one thing. Teaching that same robot when it’s safe to cross a road is quite different. That’s the core of the project carried out by Scheutz and Briggs. They wanted to give a robot the ability to reject orders it’s given, if it seems that carrying out the task would cause it harm.

To a human, this might seem like an implicit element of the action of moving around. But robots don’t have “common sense.”

Importance of the word ‘no’

Teaching a robot to refuse an order that sends it plunging to its doom is of obvious benefit to the robot, and also to whoever owns it. But its importance reaches far deeper. Helping a robot say “no” means helping it learn to judge the implications of its actions.

“The same way we do not want humans to blindly follow instructions from other humans, we do not want instructible robots to carry out human orders without checking what the effects are,” Scheutz told Digital Trends.

We have to teach robots to disobey commands that are not ethically sound.

“Instructions can be inappropriate in a given situation for many reasons,” he continued, “but most importantly because they could cause harm to humans or damage property, including the robot itself. By reasoning about possible outcomes of an instructed action, the robot might be able to detect potential norm violations and potential harm resulting from the action, and could attempt to mitigate them.”

Essentially, when the robot receives its instruction to walk forward, it checks that request against the information it has at hand. If anything seems fishy, the robot can then raise its concerns to the human operator, eventually rejecting the command outright if the instructor has no extra data to calm its fears.

The scientific process doesn’t make for as catchy a headline as the threat of a robot uprising to us humans. Tabloid newspapers like the Daily Mail reported on Scheutz’s work with a cartoonish headline speculating about our species’ impending subjugation at the hands of robot overlords. We here at DT are known to joke about the robot apocalypse, too. It’s usually in good fun, but in cases like this, it can harm researchers ability to get their message out.

“There will always be responses that take research out of context and focus on what seems uncomfortable for us, such as the idea of robots disobeying our commands,” Scheutz said in response to the Daily Mail report. “However, the key aspect of our research that such catchy headlines ignore is to teach robot to reject commands that are not ethically sound — and only those. Not to be disobedient in general.”

What if, for example, a small boy told a household robot to dump hot coffee over his little brother as a prank? Ensuring that this couldn’t take place is vital to the success of any company producing such technology for the consumer market, and it’s only possible if the robot has a broad database of social and ethical norms to reference alongside its ability to say “no.”

Adding layers of complexity

Humans know to stop walking when approaching a steep drop, or why it’s inappropriate to douse an infant in hot coffee. Our experiences have told us what is dangerous, and what’s just mean. Whether we’ve done or been told about something in the past, we can draw upon the information we have stored away to inform our behavior in a new situation.

Robots can solve problems based on the same principle. But we’ve yet to produce a computer that can learn like a human — and even then, learning ethics is a process that takes years. Robots must have a lifetime of information available to them before they’re unleashed out into the world.

The scale of this work is staggering, far beyond what many might expect. As well as teaching the robot how to fulfill whatever task they’re being sent out to do, there’s an added layer of complexity offered up by the many intricacies of human-robot interaction.

Andrew Moore is the Dean of the School of Computer Sciences at Carnegie Mellon University. In that role he provides support for a group 2,000 students and faculty members, many of whom are working in fields related to robotics, machine learning, and AI.

“We’re responsible for helping figure out what the year 2040 is going to be like to live in,” he told me. “So we’re also responsible for making sure that 2040 is a very good year to live in.” Given that it’s likely that helper robots will play a role in that vision of the future, Moore has plenty of experience in the relationship between machine and user. To give an idea of how that bond is going to evolve in the coming years, he uses the familiar example of the smartphone assistant.

Today, many of us carry a smartphone that’s able to answer questions like “who is the current President of the United States?” and more complex queries like “how tall are the President of the United States’ daughters?” Soon, we’ll see actions based on these questions become commonplace. You might ask your phone to order a new package of diapers, for instance.

To demonstrate the next stage of development, Moore put forward a seemingly innocuous example question. “Do I have time to go grab a coffee before my next meeting?”

More on AI: Machine learning algorithm puts the words of George W. Bush in Barack Obama’s mouth

“Under the hood, there’s a lot of knowledge that has to get to the computer in order for the computer to answer the question,” Moore said. While today’s technology can understand the question, the system needs a lot of data to answer. What’s the line like at the coffee shop? How is traffic? What kind of drink does the user usually order? Giving the computer access to this data presents its own challenges.

AI systems will need access to a huge amount of information — some of which is cast in stone, some of which is changing all the time — simply to carry out the complex tasks we’ll expect from them in just a few years.

Moore illustrates this point by comparing the tone of voice a person might take when speaking to their boss’ boss, or an old friend. Somewhere in your data banks, there’s a kernel of information that tells you that the former should be treated with certain social cues that aren’t as necessary when talking to the latter.

If you ask Google to show red dresses, and one of the results is a toaster, the whole thing falls apart.

It’s simple stuff for a human, but something that has to be instilled in AI. And the more pressing the task, the more important precision becomes. Asking an assistant if you have coffee is one thing. But what if you were hurt, and needed to know which hospital could be reached most quickly — and possibly needed a robots help to reach it? A mistake suddenly becomes life-threatening.

“It’s actually quite easy to write a machine learning program where you train it with lots of examples,” said Moore. “When you’ve done that work, you end up with a model. That works pretty well, and when we build a system like that, we talk about ‘accuracy’ and use phrases like ‘precision’ and ‘recall.’ The interesting thing is, it’s pretty straightforward to get things that are correct 19 times out of 20.”

“For many applications, that’s sort-of good enough. But, in many other applications — especially when there’s safety involved, or where you’re asking very complicated questions — you really need your system to have 99.9 percent accuracy.”

User trust is also an issue. “[If] you ask Google ‘show me the 15 most popular red dresses’ and it throws up the results and just one of them is actually a toaster, then the whole thing falls apart. The users stop trusting it.” A user who loses trust in a robot is likely to stop using it entirely.

Teaching common knowledge

Even disregarding the specific tasks any individual implementation is designed to achieve, robots and AIs will need a huge amount of basic knowledge to operate in the wild. Everything from social cues to safety regulations must be imprinted upon machine brains to ensure their success.

Fortunately, other fields are lending a hand in some elements of this computational curriculum. “With things like navigation, and with human facial expression analysis, there is an existing scientific discipline which actually has a lot of real data,” said Moore. Individual research projects can often be re-purposed, too.

“The algorithms we are working on are general,” Matthias Scheutz told me, referring to the research he and Gordon Briggs led at Tufts University. “They can be applied in any domain, as long as the robot has the necessary representations of actions and norms for that domain.”

Modules that could give a robot the ability to recognize human expressions, or stop short of falling off a table, certainly have their uses. However, each would cater to a very small part of a machine’s basic requirements for operating unsupervised. A generalized OS could present a basic level of common knowledge that could be easily shared between different implementations.

“One of the major funders of this kind of work is a group that’s funded many other things that turned out to be important,” said Moore. “That’s DARPA. They have a number of big projects going in what they call ‘common knowledge for robotics.'”

If AIs and helper robots are going to become a reality in the not-too-distant future, some version of this ‘common knowledge for robotics’ platform is likely to be a crucial component. It might even be the key to broad mainstream adoption.

There’s plenty of work to be done before there’s a knowledge base that can support the first wave of consumer robots. The end product might be years away, but the foundations needed to facilitate its creation aren’t science fiction.

Editors' Recommendations

- We may have just learned how Apple will compete with ChatGPT

- Microsoft Bing and Edge are getting a big DALL-E 3 upgrade

- Microsoft says bizarre travel article was not created by ‘unsupervised AI’

- AI breakthroughs could come via the brains of bees, scientists say

- AI ‘godfather’ says fears of existential threat are overblown