Part of the reason Digital Trends’ gaming editor Ryan Fleming wanted a column devoted to import gaming and game development outside the United States is because, even though gaming is a global affair, there are still plenty of titles being developed for specific regions. Sailor Moon la Luna Splende for Nintendo DS is only available in Italy. Dragon Quest VII for Nintendo 3DS remains a Japanese exclusive. The English-language version of Aquanauts Holiday for PS3? You’ll have to get it from Hong Kong. Digital distribution and the reign of PC architecture may be making games more accessible than ever, but there are some treasure that remain locked to a particular region. One of the men responsible for the contours of this gaming landscape and arguably for helping create the video game industry as we know it, Hiroshi Yamauchi, passed away this week.

Yamauchi, the president of Nintendo from 1949 to 2002, passed away after 85 years, most of which he spent spent voraciously building the business he took over from his grandfather. In the 1970s, when video games were still largely American and European pursuits, he went from importing arcade hardware to re-appropriating it for Nintendo to make its own games. Donkey Kong was born from a surplus of arcade boards.

His great innovation though, was pursuing the development of the Famicom/Nintendo Entertainment System, a machine that wasn’t super high-tech and was relatively easy to develop for. That machine was the catalyzing force that made video games the international pastime they are today.

What does the world of video games look like without Hiroshi Yamauchi? Would game consoles even exist at this point? The NES single-handedly resurrected the console business after its biggest success, the Atari 2600, imploded under a tide of awful software. Other machines like the Magnavox Odyssey, never penetrated the market in comparable numbers. Other devices like the Commodore 64 and the Amiga were multi-functional PCs; they weren’t devoted just to video games.

Without Hiroshi Yamauchi, Nintendo would have never partnered with Sony to make a CD-ROM add on for the Super Nintendo, and that relationship would never have gone sour. There would be no PlayStation.

If there was no PlayStation and its attendant massive older audience in the 1990s, Microsoft would likely have never invested in developing the Xbox to try and capture that market. There would be no Xbox 360, no Halo, no Xbox One.

Try this one: If there is no Hiroshi Yamauchi, he’s not there to hire his family friend’s son, Shigeru Miyamoto. Thus there’s no Super Mario Bros. If there’s no Super Mario Bros., then a teenage programmer named John Carmack will never build the groundbreaking engine for his PC that emulates the background scrolling in Super Mario Bros. 3. If he doesn’t make that engine, he doesn’t make Wolfenstein 3D and Doom with his friends. If he doesn’t make those games, the first-person shooter boom never happens.

Sure, it’s somewhat absurd to point to Yamauchi as the single focal point in all of these events, the stone that was thrown into the pond from which the ripples of our modern gaming age come from. Of the many factors that did though, he is among the most significant. His insistence on approving the development and release of every game means he’s in part responsible for many of the medium’s most beloved institutions. Metroid, The Legend of Zelda, F-Zero, Punch-Out!!, and many, many others. Even the Nintendo DS, the last project he was instrumental in backing, demonstrates how Yamauchi’s influence looms large in contemporary gaming.

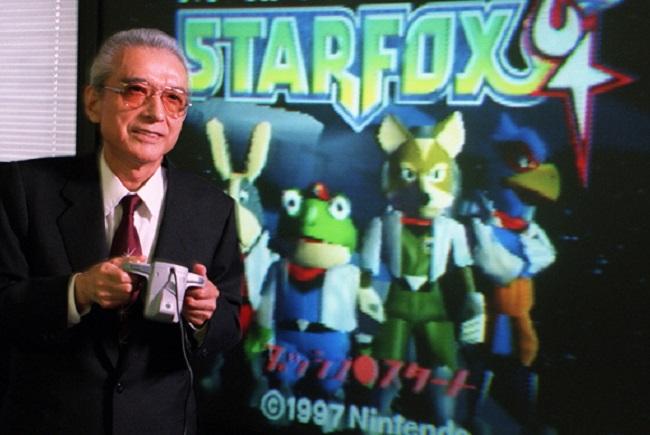

This week, Jetsetter pours one out to the old man in the big glasses. Without you, this column would not exist.