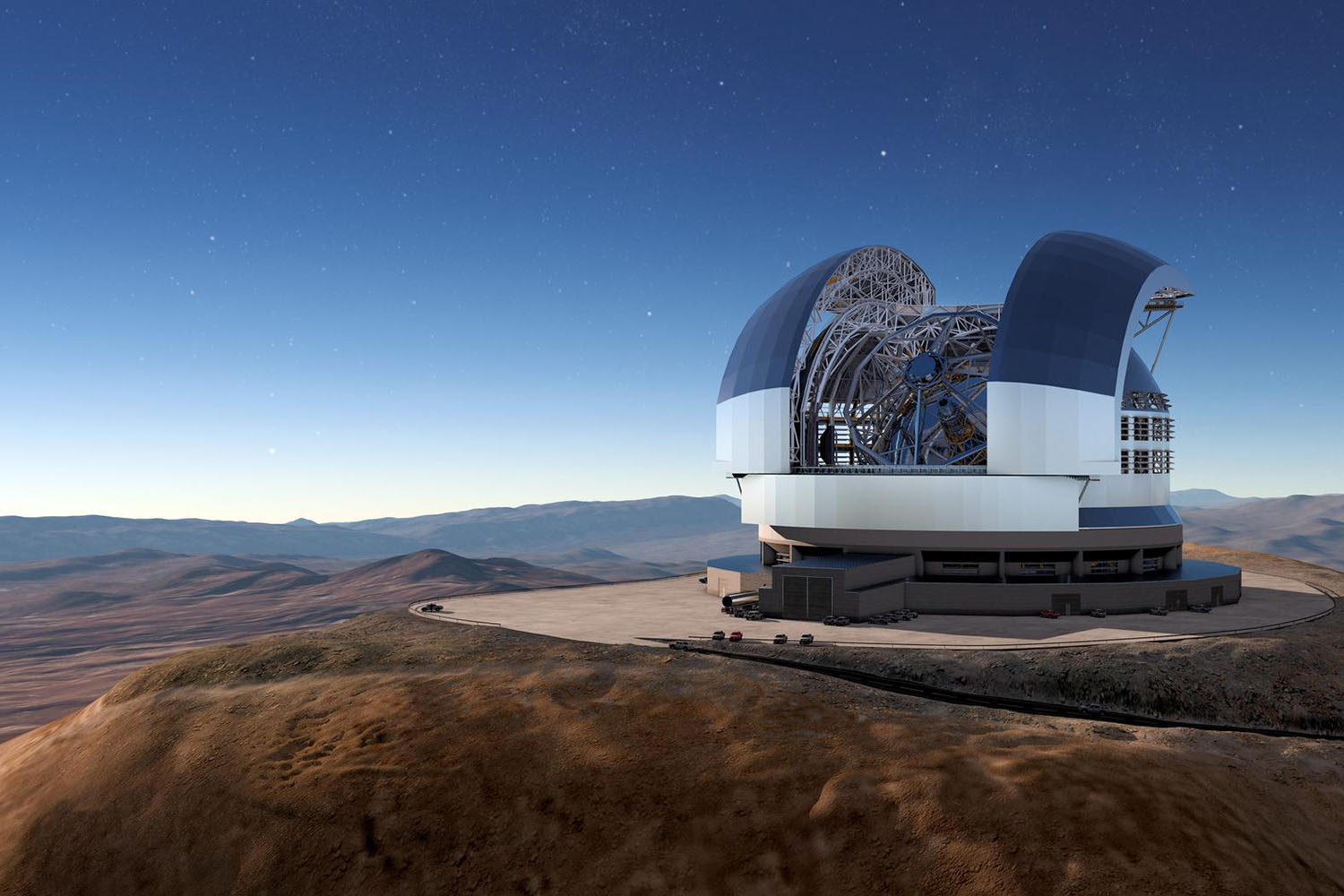

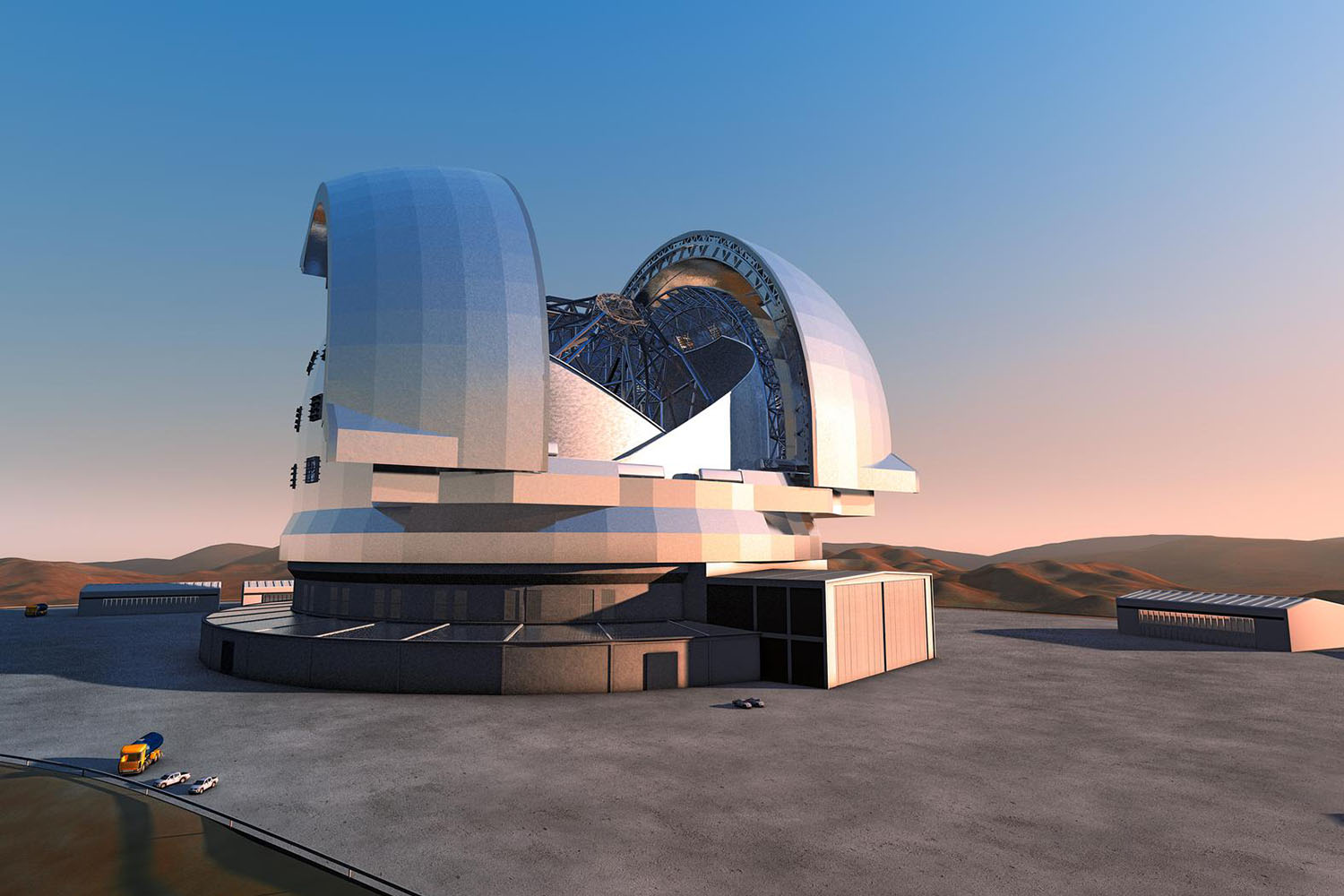

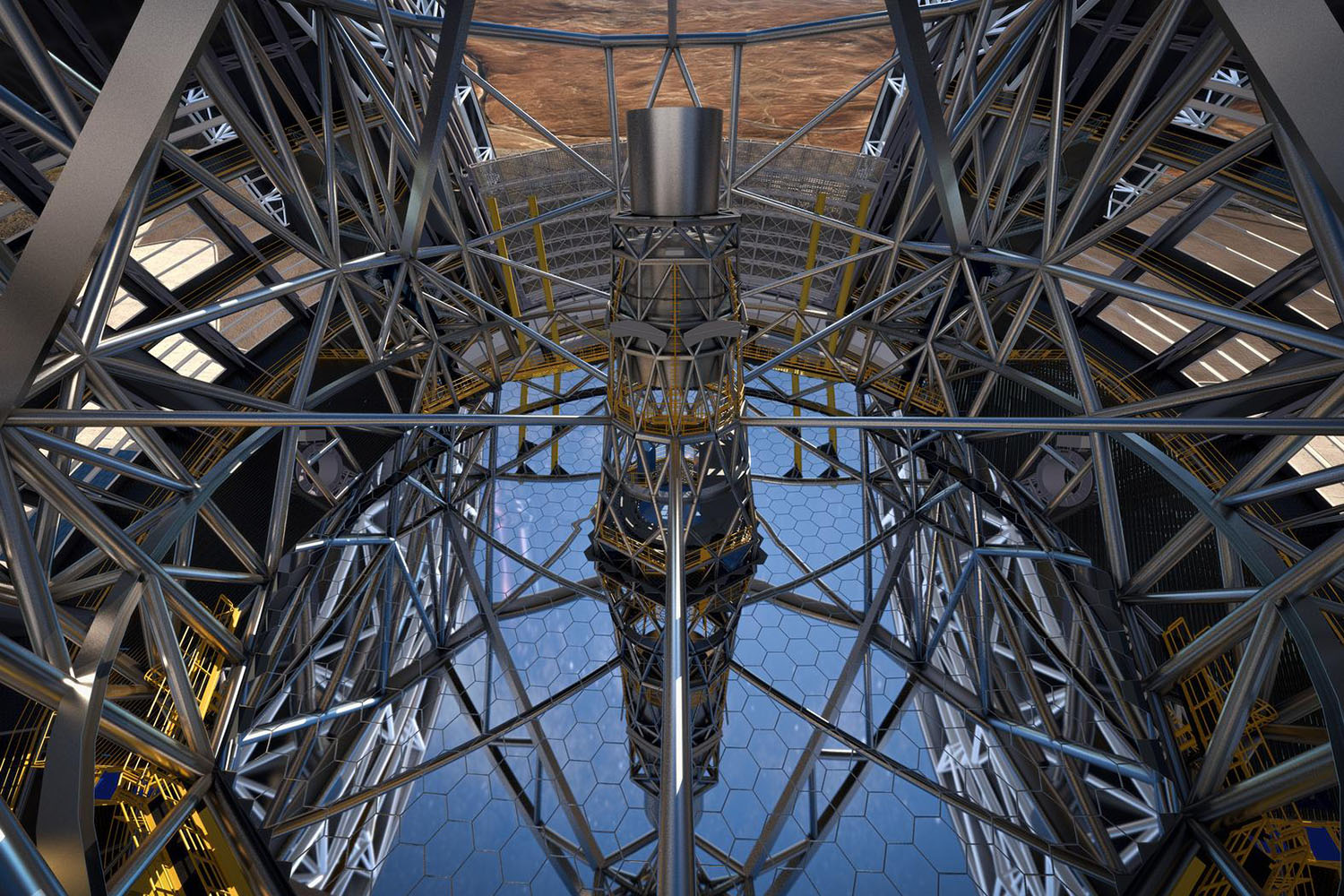

But size alone won’t make the ELT unique. The telescope will be unparalleled in clarity as well.

“It is an adaptive telescope,” Niranjan Thatte, an Oxford astrophysicist who will work with the telescope, told Digital Trends. “[This] means that it has built into it a mechanism … for compensating the effects of atmospheric turbulence, allowing the telescope to deliver much sharper images than typical ground-based telescopes.”

Thatte serves as principal investigator of HAROMNI, a visible and near-infrared instrument that will be designed to snap thousands of images at once, each in a different color.

“It is a workhorse instrument, designed to carry out a large variety of science observations, from observations of planets around nearby stars, and in our own solar system, to the most distant galaxies,” Thatte said. “It will improve our understanding of how galaxies formed and evolved.”

As an integral field spectrograph, HARMONI will be capable of capturing 4,000 images simultaneously. Thatte’s research team will use these images to study distant celestial structures, like galaxies and solar systems, to determine their mass, age, and chemical makeup.

ELT is scheduled for completion in 2024. Although Thatte expects to conduct great science once it’s launched, he acknowledges that many of our most pressing questions may change in the next seven years.

“Personally, I feel that the real groundbreaking discoveries from ELT will be those that we cannot plan today – the telescope and its instruments will allow new ‘parameter space’ to be explored – observations markedly different from any that we imagine today,” he said. “It will be these unforeseen uses that will likely yield truly remarkable physical insights into the way the universe works.”

Editors' Recommendations

- See planets being born in new images from the Very Large Telescope

- See a festive cosmic chicken captured by the VLT Survey Telescope

- Swatch lets you put a stunning Webb space image on a watch face

- Saturn as you’ve never seen it before, captured by Webb telescope

- Roman Space Telescope will survey the sky 1,000 times faster than Hubble