Can a bridge be racist?

It sounds ridiculous, but that’s exactly the argument sociologist Langdon Winner makes in “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” — a classic essay in which he examines several bridges built over roadways in Long Island, New York.

Many of these bridges were extremely low, with just nine feet of clearance from the curb. Most people would be unlikely to attach any special meaning to their design, yet Winner suggested that they were actually an embodiment of the social and racist prejudices of designer Robert Moses, a man who was responsible for building many of the roads, parks, bridges, and other public works in New York between the 1920s and 1970s.

With the low bridges, Winner wrote that Moses’ intention was to allow only whites of “upper” and “comfortable middle” classes access to the public park, since these were largely the only demographics able to afford cars at the time. Because poorer individuals (which included many people of color) relied on taller public buses, they were denied access to the park, as these buses were unable to handle the low overpasses and were therefore forced to find alternative routes.

As New York town planner Lee Koppleman later recalled, “The old son of a gun … made sure that buses would never be able to use his goddamned parkways.”

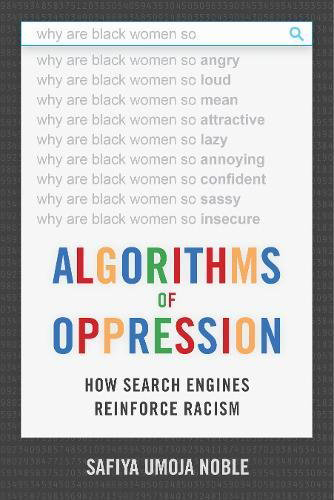

Jump forward the best part of 40 years and Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble, part of the faculty at the University of Southern California (USC) Annenberg School of Communication, has written a book that updates Langdon Winner’s critique for the digital age.

Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression makes the argument that many of the algorithms driving today’s digital revolution (she focuses particularly on those created by Google) are helping to marginalize minorities through the way that they structure and encode the world around us. They are, quite literally, a part of systemic racism.

Discriminatory patterns

Before she earned her PhD, Noble was in the advertising industry where, she told Digital Trends, one of the big discussions was about “how to game Google for our clients, because we knew that if we could get content about our clients on the first page, that’s what mattered.”

A few years later, she glimpsed this world of search engine optimization and prioritization from another angle when a friend mentioned the search results presented when a person looks for the term “black girls.”

“The first page was almost exclusively pornography or highly sexualized content,” she said. “I thought maybe it was a fluke, but over the next year I did the same for other identities, such as Asian girls and Latinas.”

The same thing held true: frequent pornographic results, even when the search terms didn’t include suffixes like “sex” or “porn.” “That’s when I started taking seriously that this wasn’t just happening in a random way, and thought that it was time for a more systemized study.”

“…I started taking seriously that this wasn’t just happening in a random way.”

Noble isn’t the first person to spot worrying discrimination embedded into tools that many of us still believe are objective. Several years ago, the African-American Harvard University PhD Latanya Sweeney noticed that her search results were accompanied by ads asking, “Have you ever been arrested?” These ads did not appear for her white colleagues.

Sweeney began a study ultimately demonstrating that the machine-learning tools behind Google’s search were inadvertently racist, linking names more commonly given to black people to ads relating to arrest records.

It’s not just racial discrimination, either. Google Play’s automated recommender system has been found to suggest that those who download Grindr, a location-based social-networking tool for gay men, also download a sex offender location-tracking app.

In both cases, the issue wasn’t necessarily that there was a racist programmer responsible for the algorithm, but rather that the algorithms were picking up on frequent discriminatory cultural associations between black people and criminal behavior and homosexuality and predatory behavior.

Who has the responsibility?

Noble makes the point in her book that companies like Google are now so influential that they can help shape public attitudes, as well as reflect them.

“We are increasingly being acculturated to the notion that digital technologies, particularly search engines, can give us better information than other human beings can,” she said.

“The idea is that they are vetting the most important information, and provide us with [objective answers] better than other knowledge spheres. People will often take complex questions to the web and do a Google search rather than going to the library or taking a class on the subject. The idea is that an answer can be found in 0.3 seconds to questions that have been debated for thousands of years.”

To Noble, the answer is that tech giants need to be held accountable for the results that they provide — and the harm they might cause.

“If your platform allows this kind of content to flourish, then you’re also responsible.”

“Tech companies have really invested in lobbying in the U.S. that they are simply intermediaries,” she continued. “They [claim that they] are tech companies and not media companies; they’ve designed a platform but they are not responsible for the content that flows through it. In the U.S. they do that because it means they are held to be harmless for trafficking in [things like] anti-semitism, Nazi propaganda, white supremacist literature, child pornography, and all the most hideous dimensions of the things which are out there on the web.”

She has little patience for the suggestion that tech companies like Google are simply reflecting what users search for. This is an argument Google itself made several years ago when it was taken to court in Germany for allegedly defamatory autocomplete results, linking the name Bettina Wulff, wife of the former German president Christian Wulff, with a rumor about prostitution and escorts.

“We believe that Google should not be held liable for terms that appear in autocomplete as these are predicted by computer algorithms based on searches from previous users, not by Google itself,” Google said at the time.

“If your platform has been designed in such a way as to allow this kind of content to flourish, then you’re also responsible for the way that you’ve designed your platform,” Noble said. “You cannot absolve your company from that.”

Asking the right questions

She also argues that tech companies are not as far removed from other, more traditional companies as they might like.

“When we’re talking about corporations and their impact on society,” she said. “I don’t think there are many industries that we can trace specific actions to one individual. What typically happens is that a CEO or a board of directors are held accountable if there is harm that hits communities. The tech industry doesn’t have to be different; it’s not really that different from fossil fuels or other industries that might cause harm through a particular product that’s been developed.”

Finally, she calls for better training of those developing the algorithms that dictate which information is shown to us.

“If you are going to design technology for society, you should have a deep education on societal issues.”

“One of the things that is particularly frightening to me is that many of the people who are designing these technologies, and embedding their own values and world views and best judgment into them, have very limited education around the liberal arts, humanities, or the social sciences,” Noble said. “They typically come into engineering curriculums where they are hyper-focused on theoretical or applied math … A lot of them are operating on twelfth-grade level humanities instruction … If you are going to design technology for society, you should have a deep education on societal issues.”

The arguments she makes in Algorithms of Oppression are incisive and provocative. While Google and other tech companies have taken steps to solve some of the most egregiously high profile issues (my top search for “black girls” leads to Black Girls Code, a San Francisco tech training initiative for underrepresented youth), problems such as this will happen with greater frequency as platforms such as Google, Facebook, and others play an increasing role in our lives, with ever more information to parse.

There are no easy solutions. How much do search results influence public opinion? Are tech companies qualified to make value judgements about what is and isn’t acceptable? Should search engines display answers that are purely based on what gets clicks, even when these results are offensive or even harmful? Will making companies responsible for their content mean that they err on the side of censorship, even when the material doesn’t warrant it? These are conundrums that companies like Google will face as they grow ever larger.

Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble doesn’t have all the answers. But she’s asking the right questions.

Editors' Recommendations

- Algorithmic architecture: Should we let A.I. design buildings for us?

- Google’s A.I. can now detect breast cancer more accurately than doctors can

- Your Alexa speaker can be hacked with malicious audio tracks. And lasers.

- Google’s soccer-playing A.I. hopes to master the world’s most popular sport

- A.I. can spot galaxy clusters millions of light-years away