We know that our galaxy is peppered with stellar-mass black holes, which were formed when massive stars ran out of fuel and collapsed in on themselves. But scientists thought that such stellar black holes could only reach a certain size — about 20 times the mass of our Sun. Now, new findings show that this assumption is incorrect, as an international team of astronomers has discovered a monster black hole around three times that size hiding out in our very own galaxy.

“Black holes of such mass should not even exist in our Milky Way galaxy, according to most of the current models of stellar evolution,” Dr. Jifeng Liu, an astronomer at the National Astronomical Observatory of China, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said in a statement. “We thought that very massive stars with the chemical composition typical of our galaxy must shed most of their gas in powerful stellar winds, as they approach the end of their life. Therefore, they should not leave behind such a massive remnant.”

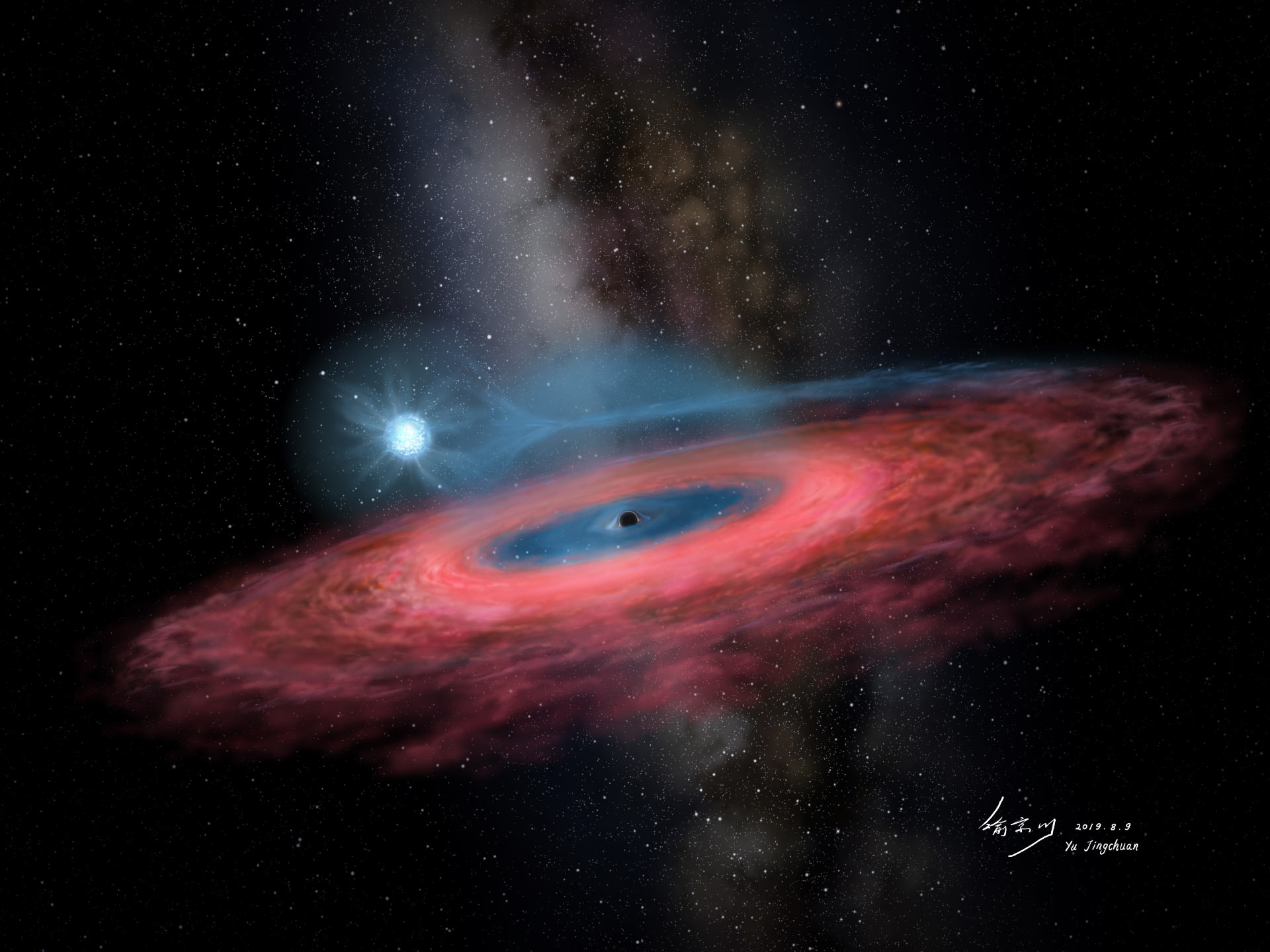

And yet, the new black hole, located in LB-1, a binary system 13,800 light-years away consisting of the black hole and a star partner, is huge — 68 times the mass of our Sun. Its binary partner is a subgiant B-type star which is around 9 times the size of our Sun and 8.2 times its mass.

Scientists had previously met with clues that black holes of this size could exist, using data from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) facility which can detect gravitational waves. These waves are formed when massive black holes collide in distant parts of the universe, sending out ripples in space-time. The collisions observed so far suggested the black holes which were colliding were much larger than typical black holes were thought to be.

With the discovery of the LB-1 black hole, we’ve found evidence of a massive black hole right in our backyard, cosmically speaking. “This discovery forces us to re-examine our models of how stellar-mass black holes form,” LIGO Director Professor David Reitze from the University of Florida said in a statement.

The findings are published in the journal Nature.

Editors' Recommendations

- ‘Closest black hole’ isn’t actually a black hole, but a stellar vampire

- Monster black hole gives off epic radio emissions as it chows down on gas

- Closest pair of supermassive black holes is merging into one mega black hole

- This black hole is creating enormous glowing X-ray rings

- Astronomers get closest look yet at epic explosion in our ‘cosmic backyard’