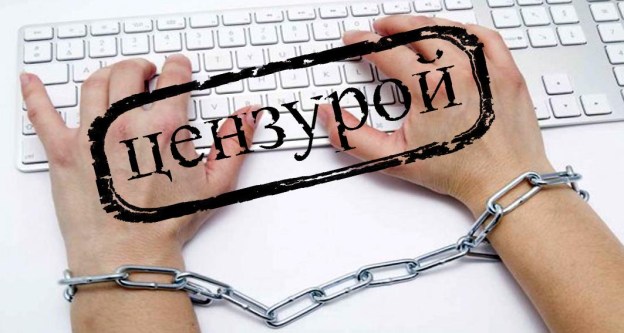

Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites are complying with a Russian law with a questionable criterion for offensive posts. But this cooperation harms freedom of speech more than it protects people – and the queue of blacklisted material continues to grow.

Facebook, Twitter and other social media sites are complying with a Russian law with a questionable criterion for offensive posts. But this cooperation harms freedom of speech more than it protects people – and the queue of blacklisted material continues to grow.

If you remember SOPA/PIPA, you know that sometimes laws intended to halt illegal behavior can end up limiting Internet access. And that’s what opponents to a Russian Internet law that aims to block Internet pages it deems harmful to children are concerned. Of course, protecting children from seeing harmful content is a good idea, but the way it’s being enforced casts doubt on its efficacy. Innocent websites and Internet users are getting caught in the crosshairs and penalized for innocuous statements.

The law, signed in July 2012, is called “On the Protection of Children from Information that is Harmful to their Health and Development.” It requires oversight from a federal watchdog service called Roskomnadzor, so sites that fail to comply get blocked in Russia. This week, the group put 1,500 sites on its blacklist for showing suicide-related content.

The new watchdog list is available online, and it takes anonymous complaints about content. If someone reports a website for having offensive content, the site has three days to remove the problem information before being blocked. The objective is to stop content like child pornography from reaching citizens – something few would object to – but the interpretation of which posts are harmful is alarmingly broad, and the procedure for deciding who gets blocked has no judicial oversight.

And now U.S.-based social networks are getting entangled in the proceedings.

In one instance, Twitter user @sult had one of his tweets blocked for promoting suicide. But far from giving children instructions to commit suicide (which is what the law is supposed to stop), his tweet contained obviously heightened, comedic language.

Twitter still complied with removing this tweet, potentially to avoid getting flat-out blacklisted. Twitter did not respond to our request for comment, but Roskomnadzor released a statement that said Twitter is ““actively engaged in cooperation.” Twitter is also complying with additional requests to remove material related to suicide and drug distribution. Twitter has commented at length about how it will honor different countries’ free speech regulations, so the move is not surprising – these tweets are deleted from Russian users’ streams, but not ours.

And Facebook’s taking a similar approach. The social network recently took down a page that Roskomnadzor thought promoted suicide called “Club Suicid.” Though Facebook allows controversial humor groups, the page was deemed a viable enough threat to remove.

Twitter and Facebook aren’t the only places content is getting swallowed by the blacklist. Lurkmore, a popular Russian Wikipedia parody site, was placed on the blacklist in November 2012, though it is explicitly a satirical site. And thought it was removed from the list and allowed back onto Russian computers, Lurkmore had to delete a specific article that referenced drugs in January 2013.

The Agora Human Rights Association paints a bleak picture of Internet freedom in Russia, and released a report stating that “A significant increase in the number of cases of restrictions of Internet freedom by the Russian authorities was identified. This can be seen in practically all areas, cases involving prosecution of Internet users went up, as did the number of blocked sites, and administrative pressure was stepped up.” (The full report’s in Russian, but it’s here.)

Russia’s law is clearly overstepping its stated intentions by penalizing content that though it might be controversial, isn’t harmful. It will be interesting to see how the implementation of the law progresses. Outgoing FCC chair Julius Genachowski explicitly criticized this policy when it was passed in July, calling it “a troubling and dangerous direction.” No doubt the chairman is displeased by how the law is progressing – according to the Russian Legal Information Agency, the amount of blacklisted sites has tripled over the past two weeks, so Roskomnadzor is not slowing down anytime soon – especially since it has cooperative allies in Twitter and Facebook.

Editors' Recommendations

- YouTuber gets more than just clicks for deliberately crashing plane

- What the biggest tech companies are doing to make the 2020 election more secure

- Facebook reportedly considering ‘kill switch’ if Trump contests 2020 elections

- YouTube has a lot more misleading coronavirus videos than we thought

- Online platforms like Facebook are losing yet another ‘infodemic’ war