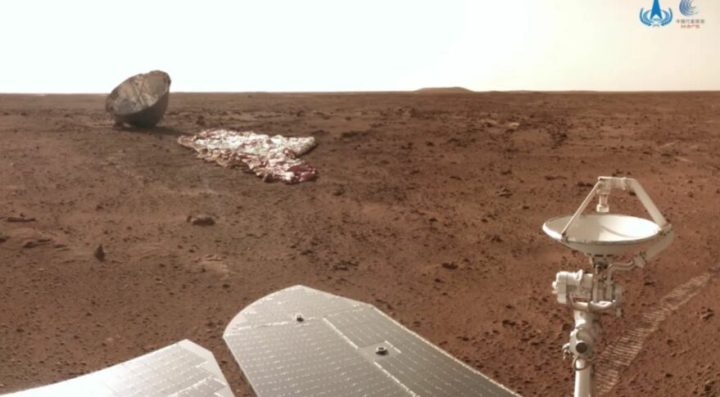

China’s Zhurong rover is exploring the surface of Mars and recently stopped by the site of its parachute and backshell. It snapped the picture above, which was shared by China’s space agency, the China National Space Administration.

The rover visited the site where its backshell and parachute fell during its landing process on May 14. The backshell is the curved piece that protects the rover from the heat generated during landing, and the parachute helps to slow the lander as it passes through the thin atmosphere. Once the lander has slowed and begun to use its retro-propulsors to touch down slowly on the ground, the shell and parachute are no longer necessary. They are jettisoned so that the lander and the rover don’t get tangled in them when the rover is deployed.

According to CNSA, the image was snapped about 30 meters away from the backshell, which is around 350 meters away from the rover’s landing site. Zhurong used its navigation terrain camera to capture the image as it was passing by during its exploration to the south of its landing place.

As well as visiting the parachute, Zhurong has been busy exploring the Utopia Planitia area. By July 18, the rover had traveled a total of 509 meters, according to the Chinese state media website Xinhua. It is currently heading toward a second sand dune that it will survey, as well as surveying the surrounding area.

The rover continues to operate well and has now been on the surface of Mars for 63 Martian days (or sols). A Martian day is just a little bit longer than an Earth day. The aim is for the rover to complete a mission lasting 90 Martian days in total.

Zhurong is just one part of the Chinese Mars mission, however. It traveled to the red planet along with the Tianwen-1 orbiter, which is observing the planet from orbit. The orbiter has been in orbit for 359 days, during which time it deployed a small satellite with two cameras called the Tianwen-1 Deployable Camera (TDC). The orbiter is also collecting science data with its Mars Energetic Particle Analyzer instrument.