The universe is a bit less than 14 billion years old, and because light takes time to travel, looking far enough away is like looking back in time to the start of the universe. Recently, an international team of astronomers identified the most distant astronomical object ever observed: A galaxy 13.5 billion light-years away, which formed just 300 million years after the Big Bang.

The galaxy has been named HD1 and identifying it required considerable patience and the use of four different telescopes — the Subaru Telescope, VISTA Telescope, UK Infrared Telescope, and Spitzer Space Telescope — with a total of more than 1,200 hours of observations. The distance to the galaxy was confirmed using another instrument, the Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array (ALMA), which is an array of 66 radio telescopes working together in Chile.

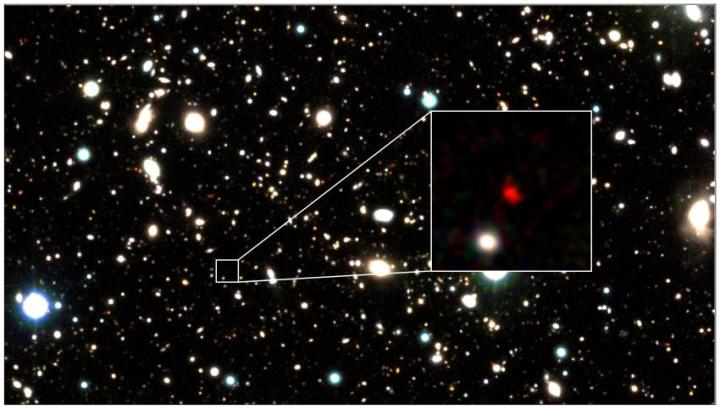

It was particularly challenging to spot the galaxy because of its extreme distance, according to Yuichi Harikane, an astronomer at the University of Tokyo who first discovered HD1: “It was very hard work to find HD1 out of more than 700,000 objects. HD1’s red color matched the expected characteristics of a galaxy 13.5 billion light-years away surprisingly well, giving me goosebumps when I found it.”

Not only is HD1 extremely far away, but it is also unusually bright in the ultraviolet wavelength. This suggests that the galaxy might be significantly different from more recently born galaxies. “The very first population of stars that formed in the universe were more massive, more luminous and hotter than modern stars,” said lead author Fabio Pacucci in a statement. “If we assume the stars produced in HD1 are these first, or Population III, stars, then its properties could be explained more easily. In fact, Population III stars are capable of producing more UV light than normal stars, which could clarify the extreme ultraviolet luminosity of HD1.”

That extreme distance makes it difficult to learn more about the galaxy as well, hence why so many hours of observation from different telescopes were needed. “Answering questions about the nature of a source so far away can be challenging,” Pacucci said. “It’s like guessing the nationality of a ship from the flag it flies, while being far away ashore, with the vessel in the middle of a gale and dense fog. One can maybe see some colors and shapes of the flag, but not in their entirety. It’s ultimately a long game of analysis and exclusion of implausible scenarios.”

The research is published in two papers in the Astrophysical Journal and Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Letters.