With the launch of Intel’s 11th-generation Rocket Lake processors, the company’s long and painful run on 14nm has finally come to an end.

Intel has already announced that Rocket Lake will be the last desktop processor to use the 14nm node, to finally be succeeded by the 10nm Alder Lake chips later this year. Its Xeon data center platform has also moved to 10nm, meaning 14nm is officially on its last legs.

With 14nm being left in the dust and a new stockpile of engineering investment ahead, Intel is finally completing its seven-year transition to 10nm. But the road to get there has been full of setbacks, resulting in one of the most difficult eras in the company’s storied history.

From tick-tock to tock-tock

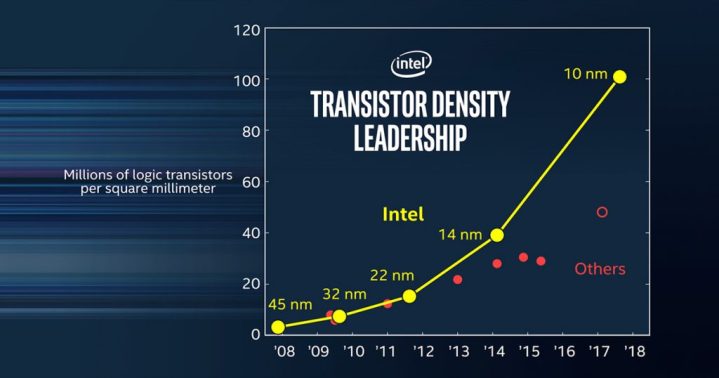

Intel used to release products in a tick-tock pattern, first adopted in 2007. This meant every other year, Intel would shrink its die size. Smaller transistors mean more transistors — all with the aim of increased efficiency, price, and performance. That fit well with the pace of innovation set by Moore’s Law and the past twenty years of processor development.

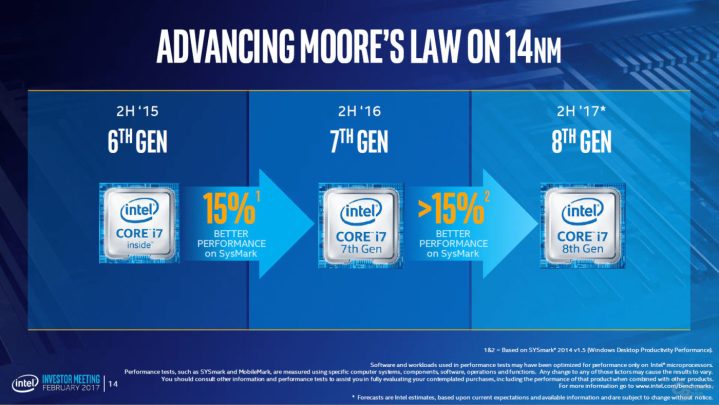

But that all changed in 2016. Cannon Lake was supposed to be Intel’s first 10nm chip, originally slated for launch in 2016. But instead, the company put out its Kaby Lake processors that year. Rather than move from 14nm to 10nm as a “tock,” the company had begun reiterate on or “refresh” its 14nm node, year after year. Thus also began the delays to the transition to 10nm, first from 2015 to 2017. Given Intel’s supreme positioning against its competitors, no one batted an eye.

But then Cannon Lake got delayed another year to 2018. And when it finally did launch, we found out just how dire the situation really was.

Cannon Lake, the first 10nm processor launched in just one configuration: The Core i3-8121U. This extremely low-volume laptop-only release was a preview of how long the full transition to 10nm would drag out. That’s not exactly the confident move we’d been waiting three years for. To support the demand for an actual refreshed launch of laptop processors, Intel was forced to release its 8th-gen Whiskey Lake processors instead.

It would be another two years until a 10nm successor to Cannon Lake would launch, known as Ice Lake. It was a big moment for Intel — real 10nm processors in actual high-end laptops that people could buy. It came with a new (and even more confusing) naming scheme, a renewed emphasis on improved integrated graphics, and some modest performance gains over the 14nm parts.

But there were two problems. First, clock speeds were very low, and volume was still lacking. Intel had to release another 14nm counterpart (codenamed Comet Lake) to supplement the demand of the market. But more than that, the low frequencies made the release limited to only thin-and-light laptops. Anything over 28 watts, such as gaming laptops or desktops, remained on 14nm.

It’s finally over. Or is it?

That’s the situation Intel still finds itself in today. Intel has slowly ramped up production on 10nm, allowing them to fully transition its low-wattage laptop chips away from 14nm. The new 11th-gen Tiger Lake is all-10nm, and most of the Intel-powered laptops you can buy in 2021 have a 10nm chip inside.

And 45-watt Tiger Lake-H processors are rumored to be coming soon, which will complete the laptop journey to 10nm. Meanwhile, 12th-gen Alder Lake chips will finish the quest for 10nm on the desktop side of the story later this year.

But as with all technology, companies are never allowed to sit on their hands and 10nm is only one stop along the way, which is where Intel’s massive $20 billion investment comes into play.

The company seems to know that it can’t afford another delay of this kind. Intel has pushed back toward a tick-tock release schedule, announcing plans to bring 7nm production in 2023.

That doesn’t mean Intel will all of a sudden be back on top. AMD and Apple have a lead, and it’s a performance gap that will continue to be a problem for Intel. But for the first time in the last few years, Intel is back on the right track — and the death of 14nm is a good sign of things to come.