A group of Australian and British geologists working in the Outback have discovered evidence of what may be the oldest-known fossils of life on Earth. The sulfur-based microbes they found are 3.4 billion years old, and might help the search for life on Mars.

In an article in Nature Geoscience, the team led by David Wacey of the University of Western Australia and Martin D. Brasier of the University of Oxford said they’d found microfossils of sulfur-metabolizing bacteria in Western Australian sandstone. Although it’s believed to be the oldest set of fossils yet found, the team decided not to officially claim that title as there has been heated infighting within the geology world over such claims.

“This goes some way to resolving the controversy over the existence of life forms very early in Earth’s history. The exciting thing is that it makes one optimistic about looking at early life once again,” Brasier told IB Times.

It’s the latest salvo in an ongoing quest to find the oldest life on Earth, and is about 200 million years older than the previous record. The bacteria survived on sulfur compounds, which has been thought to be an important transition point as early life on Earth had little to no oxygen to subsist on. And it’s because of that the team thinks similar microbes may have existed on Mars, whose early atmosphere had water and sulfur like the Earth’s did.

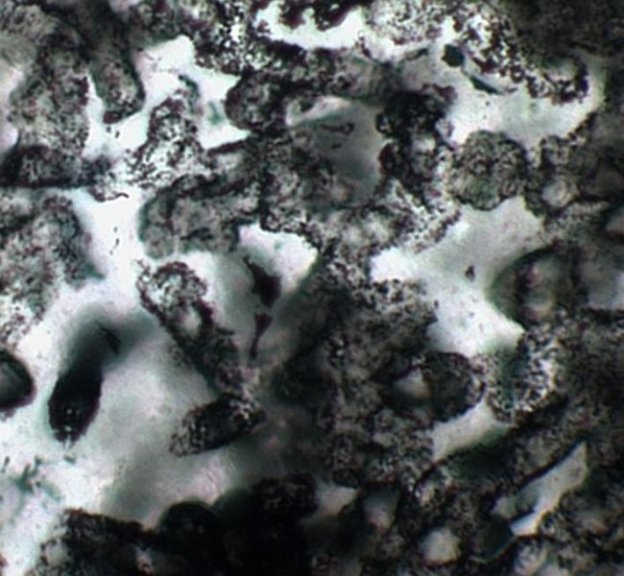

According to the letter, finding evidence of these bacteria’s structure has been “elusive,” as you might expect when discussing microscopic life that was pressed into rock nearly 3.5 billion years ago. Beating the odds, the team found fossilized cell microstructures which suggest that some of Earth’s earliest life were spheres and ellipses. Even cooler, they found evidence of multicellular tubes that may suggest that even early on in the history of life, bacteria were already organizing into higher structures.

Image: A group of the tubular fossil forms. Via David Wacey/UWA

Editors' Recommendations

- Hubble may have found the ‘missing link’ in black hole formation

- Astronomers found a comet that may have come from another solar system