While we have discovered over 5,000 exoplanets to date, most of the information we have about these planets is fairly basic. Researchers typically know about a planet’s mass or radius and its distance from its host star, but little more than that, making it hard to predict what these worlds are actually like. However, new tools and techniques are allowing researchers to learn more about details like a planet’s density, allowing a better understanding of what these places are like.

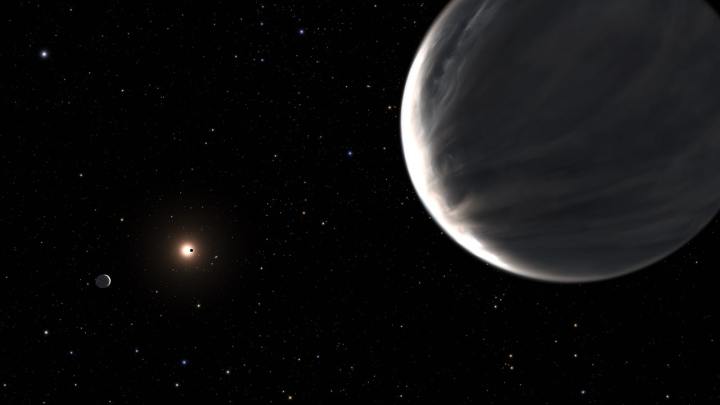

Recently, researchers using data from the Hubble Space Telescope and Spitzer Space Telescope have identified two planets that seem to be water worlds, with oceans that are 500 times deeper than the oceans on Earth.

The planets Kepler-138 c and Kepler-138 d were first identified by the Kepler Space Telescope in 2014, but it wasn’t until recently that data from Hubble and Spitzer was used to reveal their density. Research shows that up to half of the planets’ volume could be made up of water, raising questions about planets of this size and type.

“We previously thought that planets that were a bit larger than Earth were big balls of metal and rock, like scaled-up versions of Earth, and that’s why we called them super-Earths,” said one of the researchers, Björn Benneke of the University of Montreal, in a statement. “However, we have now shown that these two planets, Kepler-138 c and d, are quite different in nature and that a big fraction of their entire volume is likely composed of water. It is the best evidence yet for water worlds, a type of planet that was theorized by astronomers to exist for a long time.”

To picture what these watery worlds are like, experts say we should not be thinking about any of the planets in our solar system but rather some of the moons. “Imagine larger versions of Europa or Enceladus, the water-rich moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn, but brought much closer to their star,” said lead author Caroline Piaulet of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets. “Instead of an icy surface, they would harbor large water-vapor envelopes.”

However, these planets wouldn’t be really similar to any place in our solar system as the planets in question have extremely hot atmospheres. Instead, they would likely have a thick atmosphere of steam with liquid water at high pressure beneath.

As unusual as that sounds, we may find more similar worlds in the future. “As our instruments and techniques become sensitive enough to find and study planets that are farther from their stars, we might start finding a lot more of these water worlds,” Benneke said.