The European Space Agency (ESA) is about to perform the first-ever assisted reentry of a defunct satellite in an effort to ensure the safety of people and property on Earth.

If the maneuver is successful, any parts of the 1,100-kilogram Aeolus satellite that survive the high-speed reentry on Friday, July 28, will crash into the Atlantic Ocean.

The assisted reentry procedure involves maneuvering Aeolus into the appropriate position using the small amount of fuel that remains on the satellite.

“This is quite unique, what we’re doing,” Holder Krag, head of ESA’s Space Debris Office, said in comments reported by Space.com. “You don’t find really examples of this in the history of spaceflight. This is the first time, to our knowledge, we have done an assisted reentry like this.”

Aeolus launched in 2018 to become the first satellite to measure winds on Earth, enabling more accurate weather forecasts globally. The satellite also helped scientists to examine the aftermath of the volcanic plumes — including from the Tonga eruption in the Southern Pacific Ocean in January 2022 — with gathered data helping air traffic controllers to guide aircraft around the ash.

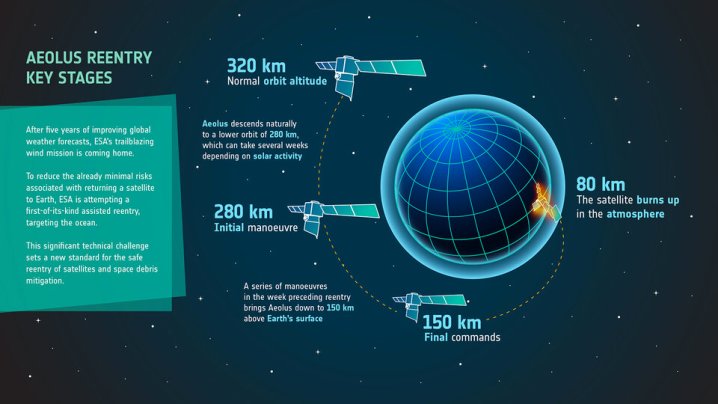

Since being powered down earlier this month, the satellite has been descending by about 0.62 miles (1 kilometer) each day from its original altitude of around 200 miles (320 kilometers).

When it reaches 174 miles (280 kilometers) on Monday, the ESA will perform the first of several critical maneuvers designed to steer the satellite slowly back to Earth, the space agency explained on its website.

The final maneuver, set for Friday, July 28, will guide Aeolus to an altitude of 75 miles (120 kilometers), at which point the satellite will reenter Earth’s atmosphere.

At around 50 miles (80 kilometers), most of the satellite is expected to burn up, but ESA says that a few fragments may reach Earth.

“Mission scientists and engineers have worked tirelessly to calculate the optimal orbit for Aeolus to reenter Earth, which targets a remote stretch of the Atlantic Ocean,” ESA said.

It points out that the risk of a falling fragment hitting someone on Earth is extremely low, and the assisted reentry process is designed to lower the risk even further.

But Krag said that with so many satellites in space, greater care needs to be taken when it comes to reentry.

“Typically, 20 to 30% of the spacecraft mass can survive the reentry, and although the likelihood of damage or injury is very small, we take this very seriously, and future spacecraft will have to be designed to do a controlled reentry,” Krag said.

ESA’s assist procedure is described as “complex and novel,” so there’s a chance it could fail. In such a case, the attempt will be aborted and Aeolus will descend without any assistance.

“Successful or not, the attempt paves the way for the safe return of active satellites that were never designed for controlled reentry,” ESA said.

Updates about Aeolus’ final days in space, and its reentry, can be found on the satellite’s Twitter feed.

Editors' Recommendations

- Get out the scrapers: Euclid space telescope is getting deiced

- Juice spacecraft gears up for first ever Earth-moon gravity boost

- Mars flyover video shows a stunning network of valleys

- Get up close to Ariane 5 rocket’s final launch in this 360-degree video

- How to watch JUICE mission launch to Jupiter’s icy moons