Black holes come in a variety of sizes, from stellar black holes a few times the mass of the sun all the way up to supermassive black holes, which are millions of times the mass of the sun and lurk at the heart of galaxies. Recently, astronomers discovered a massive black hole just 1,550 light-years away, which is right in our neighborhood, astronomically speaking. It is one of the closest black holes ever discovered, with a mass 12 times that of the sun. Being so close to us, it’s an exciting target for future research.

“It is closer to the sun than any other known black hole, at a distance of 1,550 light years,” said Sukanya Chakrabarti, lead author of the study from the University of Alabama in Huntsville, in a statement. “So, it’s practically in our backyard.”

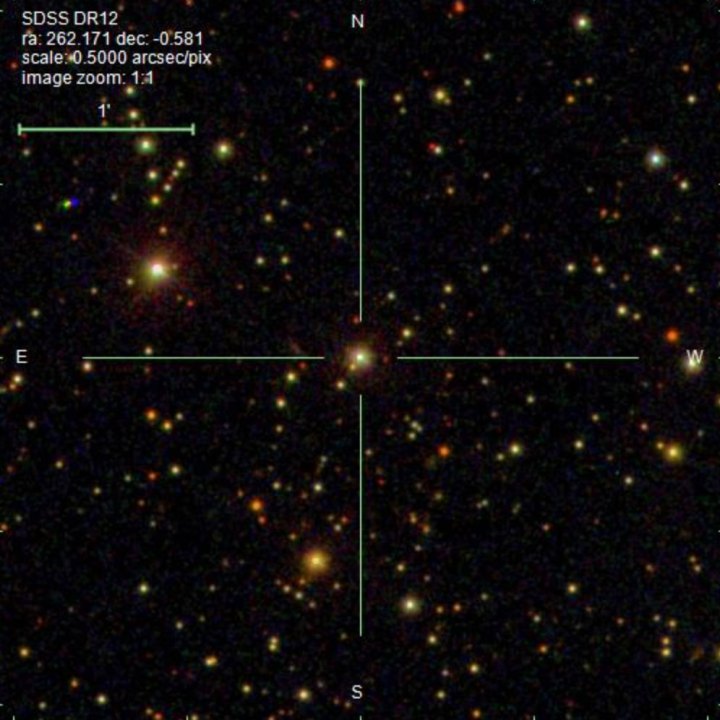

The black hole was discovered using data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia mission, which is building a 3D map of the entire galaxy. The researchers looked at nearly 200,000 binary stars, in which a star orbits a companion, to search for cases where the brightness of one star was sufficient to explain the brightness of the binary. That implies that the companion in these binaries must be dark, which suggests the companion could be a black hole.

Then, the researchers took these selected binaries and studied the Doppler shift of their light, which shows how massive the companion must be and gives information about the pair’s orbit and rotation. This is how they identified and learned about the nearby black hole.

“In this case we’re looking at a monster black hole but it’s on a long-period orbit of 185 days, or about half a year,” Chakrabarti said. “It’s pretty far from the visible star and not making any advances toward it.”

As well as finding a useful target for research because of its location, the study also demonstrates how more black holes can be identified in the future.

“Simple estimates suggest that there are about a million visible stars that have massive black hole companions in our galaxy,” Chakrabarti said. “But there are a hundred billion stars in our galaxy, so it is like looking for a needle in a haystack. The Gaia mission, with its incredibly precise measurements, made it easier by narrowing down our search.”

The research has not yet been peer reviewed but has been submitted to The Astrophysical Journal.