When it comes to searching for potentially habitable places in our solar system, one of the top targets is Saturn’s moon Enceladus. From a distance, the moon appears to be slick and shiny, covered in a thick layer of ice. But scientists believe there is an ocean beneath this ice crust that could potentially be capable of supporting life.

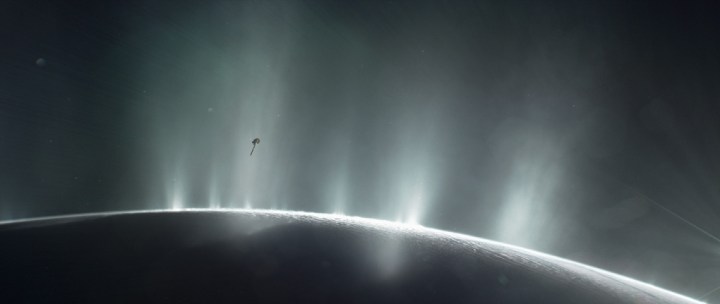

One of Enceladus’s most intriguing features is the huge plumes of water that periodically erupt from its surface. They give evidence about what the ocean beneath the ice may be like, and by flying through these plumes and taking samples, the Cassini spacecraft was able to determine that the plumes had concentrations of dihydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. These chemicals are also found in the hydrothermal vents on Earth’s ocean floor — and as these vents are known to host life, scientists have wondered if Enceladus’s ocean might be able to as well.

“We wanted to know: Could Earthlike microbes that ‘eat’ the dihydrogen and produce methane explain the surprisingly large amount of methane detected by Cassini?” said lead author of the study, Régis Ferrière, associate professor in the University of Arizona Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “Searching for such microbes, known as methanogens, at Enceladus’ seafloor would require extremely challenging deep-dive missions that are not in sight for several decades.”

As the researchers couldn’t send a mission there themselves, instead they used mathematical modeling to determine whether the conditions observed on Enceladus could be consistent with the presence of microbial life. They found that the data collected by Cassini could be explained by microbial vent activity similar to that on Earth’s ocean floor. Or it could be explained by a different process that doesn’t involve life — but it would have to be different from anything here on Earth.

So that doesn’t mean there is life on Enceladus, but it means that there could be. The current data shows a definite possibility that the ocean is habitable.

“Obviously, we are not concluding that life exists in Enceladus’ ocean,” Ferrière said. “Rather, we wanted to understand how likely it would be that Enceladus’ hydrothermal vents could be habitable to Earthlike microorganisms. Very likely, the Cassini data tell us, according to our models.”