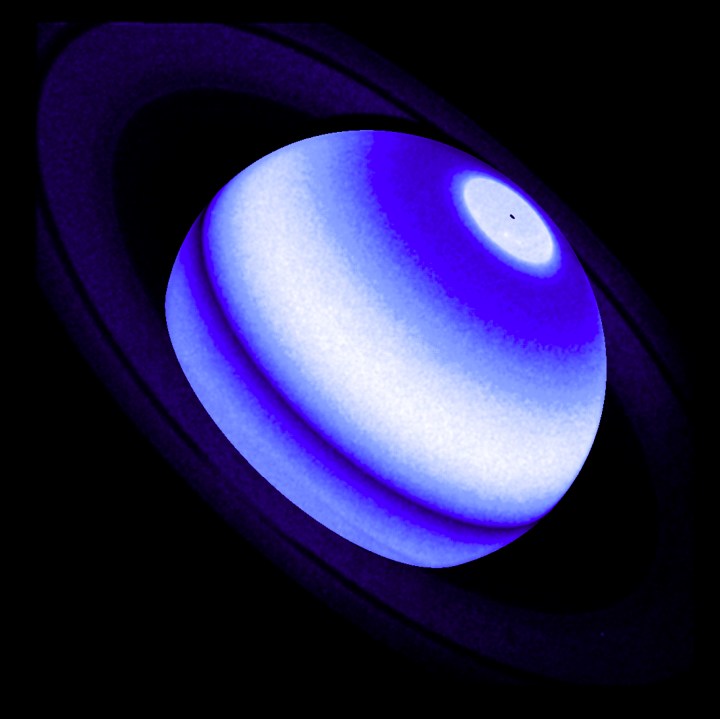

Saturn’s famous rings don’t just give the planet its distinctive look — they also affect its weather. New research using the Hubble Space Telescope shows that the icy rings actually heat up Saturn’s atmosphere, a phenomenon that could help us learn more about distant exoplanets as well.

Saturn’s rings are made up of small particles of ice, forming ring shapes that reach 175,000 miles away from the planet. And it seems that it is these icy particles that are, somewhat counterintuitively, causing heating in the planet’s atmosphere. Researchers looked at observations from Hubble as well as the Cassini and Voyager missions and saw more ultraviolet radiation than they expected in Saturn’s upper atmosphere, indicating heating there.

This heating is thought to be caused by particles from the rings, which are raining down onto the atmosphere due to forces like solar winds or micrometeorites. Over time, the rings are gradually losing particles as they fall into the planet’s atmosphere and heating the hydrogen there — and while scientists already knew about the degrading rings, the heating effect is a new finding.

“Though the slow disintegration of the rings is well known, its influence on the atomic hydrogen of the planet is a surprise. From the Cassini probe, we already knew about the rings’ influence. However, we knew nothing about the atomic hydrogen content,” said lead author of the research, Lotfi Ben-Jaffel of the Institute of Astrophysics in Paris, in a statement.

These indications of ultraviolet emissions had been seen before in observations from Cassini and the two Voyager probes which passed Saturn in the 1980s. But scientists hadn’t been sure whether the effect was real, or just a result of noise. By looking at these data alongside measurements from Hubble, the researchers were able to see the effect was a real one.

“When everything was calibrated, we saw clearly that the spectra are consistent across all the missions. This was possible because we have the same reference point, from Hubble, on the rate of transfer of energy from the atmosphere as measured over decades,” Ben-Jaffel said. “It was really a surprise for me. I just plotted the different light distribution data together, and then I realized, wow — it’s the same.”

One exciting element of this finding is that it could be applied to planets outside our solar system, called exoplanets, as well. If researchers can spot similar ultraviolet radiation coming from distant planets, that could suggest that they have rings of their own.

“We are just at the beginning of this ring characterization effect on the upper atmosphere of a planet,” Ben-Jaffel said. “We eventually want to have a global approach that would yield a real signature about the atmospheres on distant worlds. One of the goals of this study is to see how we can apply it to planets orbiting other stars. Call it the search for ‘exo-rings.'”

The research is published in the Planetary Science Journal.

Editors' Recommendations

- Saturn’s tiny moon, Mimas, hosts an unexpected ocean beneath an icy shell

- Hubble snaps an image of dark spokes in Saturn’s rings

- Super high energy particle falls to Earth; its source is a mystery

- Saturn as you’ve never seen it before, captured by Webb telescope

- This exoplanet is over 2,000-degrees Celsius, has vaporized metal in its atmosphere