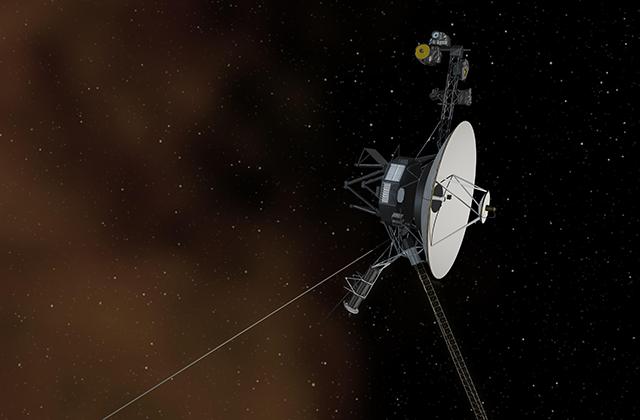

The two Voyager probes were launched in the 1970s and have now sped out of our solar system and into interstellar space — but even after more than 40 years of operation, they are still making new discoveries. Their latest finding is the discovery of a new type of electron burst, powered by the sun’s cosmic rays.

The bursts consist of electrons traveling at close to the speed of light, having been propelled by shock waves coming from the sun. The sun undergoes what are called coronal mass ejections, which are large releases of highly energetic plasma that often follow solar flares. These coronal mass ejections send hot gas and energy spewing out from the sun at a speed of one million miles per hour, creating the shock waves which then hit the electrons. The electron burst which results is even faster than the shock wave.

“What we see here specifically is a certain mechanism whereby when the shock wave first contacts the interstellar magnetic field lines passing through the spacecraft, it reflects and accelerates some of the cosmic ray electrons,” explained Don Gurnett, author of the study and professor emeritus in physics and astronomy at the University of Iowa, in a statement.

“We have identified through the cosmic ray instruments these are electrons that were reflected and accelerated by interstellar shocks propagating outward from energetic solar events at the sun. That is a new mechanism.”

This is the first time that these shock waves have been observed in the space between stars. The Voyager probes were able to detect it because they have traveled so far from Earth, out of our solar system.

“The idea that shock waves accelerate particles is not new,” Gurnett said. “It all has to do with how it works, the mechanism. And the fact we detected it in a new realm, the interstellar medium, which is much different than in the solar wind where similar processes have been observed. No one has seen it with an interstellar shock wave, in a whole new pristine medium.”