A new image from the James Webb Space Telescope shows a stunning view of a star cluster that contains some of the smallest brown dwarfs ever identified. A brown dwarf, also sometimes known as a failed star, is an object halfway between a star and a planet — too big to be a planet but not large enough to sustain the nuclear fusion that defines a star.

It may sound surprising, but the definition of when something stops being a planet and starts being a star is, in fact, a little unclear. Brown dwarfs differ from planets in that they form like stars do, collapsing due to gravity, but they don’t sustain fusion, and their size can be comparable to large planets. Researchers study brown dwarfs to learn about what makes the difference between these two classes of objects.

“One basic question you’ll find in every astronomy textbook is, what are the smallest stars? That’s what we’re trying to answer,” explained lead author of the Webb research, Kevin Luhman of Pennsylvania State University, in a statement.

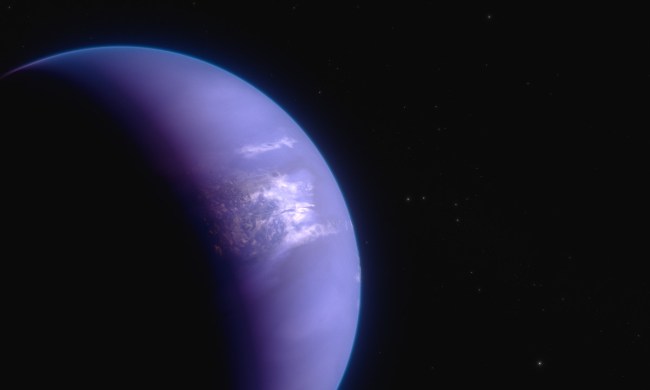

This image shows the star cluster IC 348, which is young and is located in a star-forming region called Perseus. Within this cluster, the researcher found three small objects with a mass between three and eight times that of Jupiter, with surface temperatures between 830 and 1,500 degrees Celsius. That’s hot for a planet but not hot enough to be a star. The smallest they found was just three or four times the mass of Jupiter, making it the smallest brown dwarf identified to date.

The fact the object is so small means it’s difficult to explain how it formed. “It’s pretty easy for current models to make giant planets in a disc around a star,” said researcher Catarina Alves de Oliveira of the European Space Agency. “But in this cluster, it would be unlikely that this object formed in a disc, instead forming like a star, and three Jupiter masses is 300 times smaller than our Sun. So we have to ask, how does the star formation process operate at such very, very small masses?”

The research is published in The Astronomical Journal.