If there’s one common goal most of the tech industry has invariably shared and worked toward, it’s to offer a frictionless experience. Big Tech’s relentless pursuit of getting rid of friction — a term, in design speak, reserved for any barrier that acts as an extra step users have to go through to access a service — has made modern technology easier than ever to use. Giants like Apple, Amazon, and Uber have transformed their sectors and made billions just by reducing the effort it takes to shop or hail a cab.

Think of the simple act of pulling out your phone to post on Facebook. You don’t have to punch in a code, as your phone likely unlocks itself via your fingerprint or face. The Facebook app is right there on your home screen. You’re already connected and logged in. Within seconds of tapping the icon, your post is up, and soon enough, you’re responding to comments, checking how many people liked or shared it, and so on.

While this rigorous obsession for simplification was necessary when companies were looking to upgrade from the age of dial-up internet and flip phones, it has now strayed into facile territory and failed to address the seismic shifts that have changed society’s relationship to technology over the past few years. The war on friction has led to consequences that even the much younger Mark Zuckerberg, who a decade ago at Facebook’s annual developer conference promised to deliver “real-time serendipity in a frictionless experience,” wouldn’t have anticipated.

Why dead-simple tech made life more complicated

To reduce friction is to hide the complexities behind an action. Years ago, this just meant coming up with more convenient ways to do a cumbersome job like reserving a restaurant table. Now, doing so means hiding what tech platforms are truly capable of and the extent of the power they wield. And that has spawned some of the biggest problems the tech industry is facing today.

Designers employ friction to influence — or in some cases manipulate — how we use their services.

Social media has made it possible to broadcast on a platform — one that hosts nearly a third of the world population — in a few clicks. There’s nothing inherently problematic with this, but many major platforms have a tendency to promote posts that drive the most engagement and attention, which has enabled malicious actors to dominate millions of people’s attention with intentionally divisive posts. You are notified of an update the moment it arrives and shown a piece of online content as soon as it begins to gain momentum — regardless of whether it has gone through moderation.

Similarly, Amazon’s one-button shopping experiences have exacerbated the world’s climate issues. YouTube’s autoplay function, which plays another video as soon as you’re done watching the current one — often sends viewers down a rabbit hole of conspiracy theories and other disturbing channels.

Which begs the question: Can introducing friction back into tech solve some of its biggest problems?

How friction controls your online behavior

Friction plays an instrumental role in shaping our choices online. Designers often employ it to influence — or in some cases manipulate — how we use their services.

Services that make money off of keeping you engaged usually get rid of friction entirely so that you would have to expend as little effort as possible to use their apps. like TikTok’s endless stream of videos that play automatically.

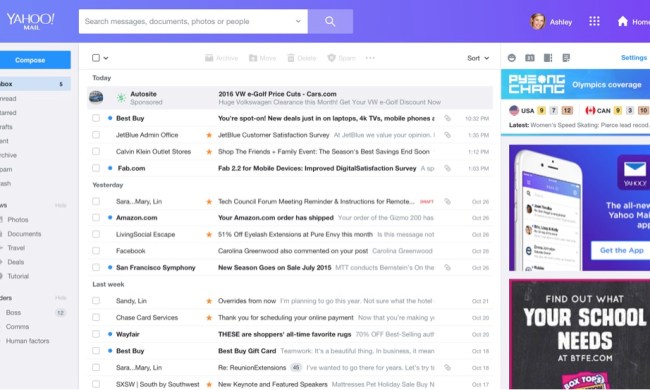

Ads, for instance, are a form of friction as well. If a company wants you to pay for a premium subscription, it will make the free version less convenient by including ads. When YouTube released its Premium tier, it began showing users two back-to-back advertisements, instead of one, before videos. If you want to eliminate that friction, you have to upgrade.

You’ll also find much less friction in accessing elements that companies want to push. Sending out a tweet takes seconds, but reporting a tweet for abuse? For that, you will have to go through a couple of hoops.

Similarly, Google doesn’t want you to restrict how much of your data its services are allowed to access. So for years, its privacy settings remained a convoluted mess that was difficult to understand for most people. It’s only recently, after several controversies and lawsuits, that Google and other tech businesses have simplified their security controls.

Friction as a force for good

Studies have concluded that intentionally designing friction into tech can enable more mindful interactions and allow people to pause and take a moment to understand the broader consequences of their decisions online.

In a research paper, Ulrik Söderström and Thomas Mejtoft, associate professors of Media Technology at Sweden’s Umea University, discovered that app designs that offered more context about how they worked left users three times more satisfied.

“Slowing down interactions and adding friction in certain situations … creates mindful interactions.”

Söderström and Mejtoft argue that the absence of friction and the rise of overly “user-friendly” services has “led to the creation of dark patterns” like how Facebook and Twitter’s own algorithms often end up fostering harmful content and misinformation.

“Slowing down interactions and adding friction in certain situations, in order to help the user understand what is going on and help them think about the decisions that they are making, creates mindful interactions,” they told Digital Trends.

Cliff Kuang, a UX designer and author of “User Friendly: How the Hidden Rules of Design are Remaking the Way We Live, Work, and Play”, argues things have now gotten so simple that the products we use have become “black boxes.”

When we conceal the assumptions and the complex calculations that drive these tech platforms under soothing buttons and animations, we also lose the ability to question and rebuild them. For instance, one of the more alarming concerns companies has struggled with is the racial bias in their personalization engines and even after years, they have barely made progress because these qualities are so deeply ingrained in their tech that it’s impossible for them to challenge it without taking apart the very products that made them successful.

By designing for instant gratification, Kuang adds, tech design prioritizes what people might want in the short term and overlooks the long-term effects. “Those two things conflict all the time, sometimes with grave consequences.”

The future is slow

Instead of instantly channeling just about everything people post into their vast networks, what if tech companies added algorithmic speed bumps that give them an opportunity to spot problematic content before it goes viral?

It could work, according to Anna Cox, professor of human-computer interaction at University College London, who proposed that adding friction or “micro-boundaries” in tech could put an end to mindless interactions. But she remains doubtful that companies would ever take such a bold step.

“Having more time to reflect on whether information should be shared is likely to lead to higher-quality data being shared (because you wouldn’t release the rubbish),” she told Digital Trends. “But, of course, this is quite at odds with how these platforms work at the moment – they share first and then inspect things later if issues are raised.”

Fortunately, a few tech companies may have already realized this to an extent. Earlier this year, Facebook rolled out an update that throws a warning every time someone tries to share an outdated article. Twitter also added a prompt that nudges users to open a link before retweeting it. WhatsApp imposed a limit on forwards to tackle misinformation and claimed it led to a 25% drop in message forwards globally.

While these small changes may seem trivial in the grand scheme of things, they are a promising step in the right direction. Twitter revealed that 33% more people are now reading articles before sharing, and the added friction (in the form of a pop-up) managed to convince 40% more people to open the link they were trying to retweet.

Alex Muench, a product designer at Doist, the startup behind the popular productivity and to-do app Todoist, finds these initiatives “very efficient” as they show that the companies are willing and able to “adapt to current events.”

“I believe this is the next frontier for design — designing for friction.”

“If preventing these issues means adding more friction, I do think that it’s a good idea in this context,” he said in an email to Digital Trends. “Here, friction should be used as a tool that encourages users to be more aware of possible misinformation and that reminds users not to be too reckless with the information they consume or spread.”

The (intentionally) bumpy road ahead

Doing things the hard way could also just be the key to digital wellbeing. Despite YouTube’s aggressive strategy to make me pay for its Premium plan, I have largely refused to succumb simply because I find those ads — that extra layer of friction — enough of a deterrent to remind me I shouldn’t be binge-watching cat videos in the middle of a workday.

Cox believes that slowing down our interactions through friction can give us just enough time to “reflect on whether our behavior matches our values” and regain control instead of mindlessly interacting with technology and moving from one app to another.

Friction, however, is a tricky line to tread, and its efficacy in these areas will depend on how well it’s implemented and whether companies do it ethically. Nevertheless, experts believe that friction needs to return to tech design in order to tackle the growing number of issues such as depreciating levels of digital well-being, as well as the proliferation of misinformation, targeted abuse, and more.

“I believe this is the next frontier for design — designing for friction,” said Steve Selzer, the head of design at Bungalow, who in an essay four years ago urged designers to design friction back into their products to restore moments for serendipity and self-reflection.