When it comes to searching for life beyond our planet, one of the most common approaches is to look for what are called biosignatures: Indications of chemicals that are produced by lifeforms, such as the recent possible detection of phosphine on Venus. But this requires making a lot of assumptions about what life looks like and how it operates — not to mention the practical challenges of trying to detect every chemical which could be relevant. Now, a team from Arizona State University has come up with a new approach to biosignatures, which can look for life more broadly and which could fit into a space probe.

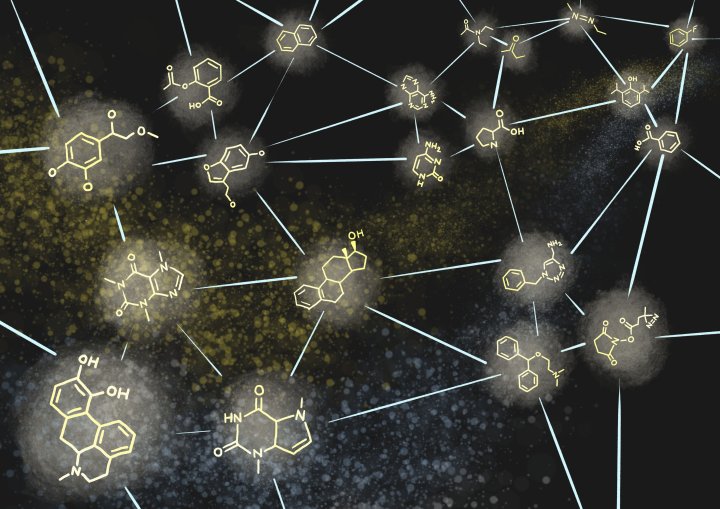

The idea is to look not for specific chemicals, but rather to look for complex molecules which would be unlikely to form in large amounts by chance. They developed an algorithm to assign a complexity score to molecules based on how many bonds they have, called the molecular assembly (MA) number. This number could be measured using equipment that fits into a space probe, and if you find a bunch of complex molecules in a given area, that’s a big clue you should look more closely there.

“The method enables identifying life without the need for any prior knowledge of its biochemistry,” said study co-author Sara Imari Walker, of ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration. “It can therefore be used to search for alien life in future NASA missions, and it is informing an entirely new experimental and theoretical approach to finally reveal the nature of what life is in the universe, and how it can emerge from lifeless chemicals.”

The clever part is that this method avoids making assumptions about what life looks like. Living things seem to reliably produce more complex molecules than non-living things, so we can follow the trail of complexity to search for life.

Not only that, but understanding more about how chemical systems process information could lead to breakthroughs in other fields as well.

“We think this will enable an entirely new approach to understanding the origin of living systems on Earth, other worlds, and hopefully to identifying de novo living systems in lab experiments,” said ASU alumnus Cole Mathis, postdoctoral researcher at the University of Glasgow and co-author. “From a really practical perspective, if we can understand how living systems are able to self-organize and produce complex molecules, we can use those insights to design and manufacture new drugs and new materials.”

The research is published in the journal Nature Communications.