There’s something odd about the black holes discovered to date. We’ve found plenty of smaller black holes, with masses less than 100 times that of the sun, and plenty of huge black holes, with masses millions or even billions of times that of the sun. But we’ve found hardly any black holes in the intermediate mass range, arguably not enough to confirm that they even exist, and it’s not really clear why.

Now, astronomers are using the Hubble Space Telescope to hunt for these missing black holes. Hubble has previously found some evidence of black holes in this intermediate range, and now it is being used to search for examples within a few thousand light-years of Earth.

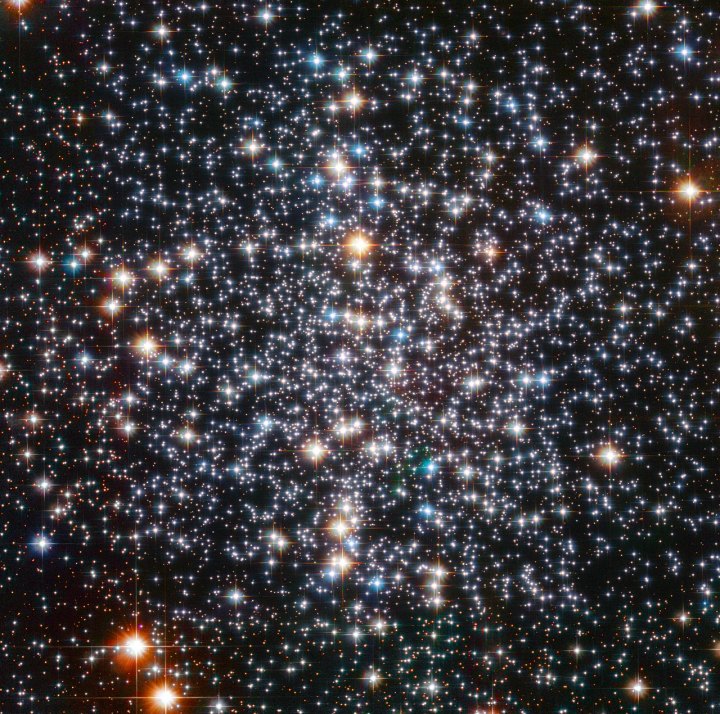

It’s tricky to spot these intermediate black holes because the effect they have on stars around them is more modest than that of the huge supermassive black holes that astronomers usually observe. Hubble has been observing targets like Messier 4, a globular cluster that is thought to hold a black hole with a mass around 800 times that of the sun. The black hole can’t be observed directly, but its presence can be inferred by looking at its subtle effects on nearby stars.

The researchers also used data from Gaia, a project to create a 3D map of stars in the Milky Way, which helped to provide information on the shape of the globular cluster. Even with these two powerful telescopes, though, it’s still difficult for researchers to know whether they are looking at a black hole or a bunch of less dense objects like neutron stars or white dwarfs.

“Using the latest Gaia and Hubble data, it was not possible to distinguish between a dark population of stellar remnants and a single larger point-like source,” explained the lead author of the research, Eduardo Vitral of the Space Telescope Science Institute, in a statement. “So one of the possible theories is that rather than being lots of separate small dark objects, this dark mass could be one medium-sized black hole.”

If there were a bunch of objects close together, they would have to be crammed together in an unstable formation. The more likely explanation is that there is one single black hole with an intermediate mass.

“We have good confidence that we have a very tiny region with a lot of concentrated mass,” Vitral said. “It’s about three times smaller than the densest dark mass that we had found before in other globular clusters. The region is more compact than what we can reproduce with numerical simulations when we take into account a collection of black holes, neutron stars, and white dwarfs segregated at the cluster’s center. They are not able to form such a compact concentration of mass.”

That means the researchers can’t be completely sure that they have found one of the elusive intermediate black holes, but it is a definite possibility. And that means there’s more exiting research to come. “Science is rarely about discovering something new in a single moment,” said Gaia mission scientist Timo Prusti. “It’s about becoming more certain of a conclusion step by step, and this could be one step towards being sure that intermediate-mass black holes exist.”

The research is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.