Of the thousands of exoplanets detected to date, all have been within the Milky Way. But now, evidence has been uncovered for the potential identification of a planet in another galaxy for the first time.

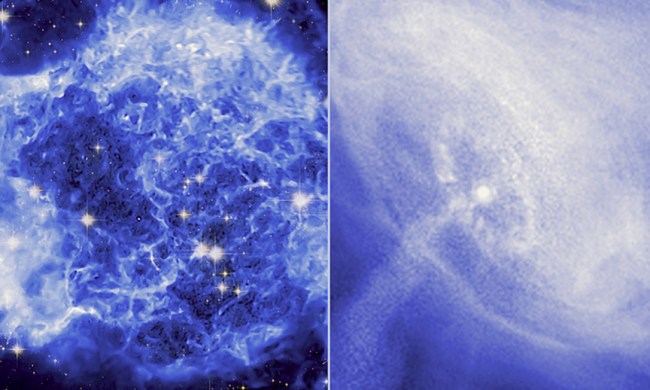

The potential exoplanet was spotted using NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory in the Messier 51 galaxy, also known as the Whirlpool galaxy thanks to its beautiful whirling shape.

At 28 million light-years away, the potential exoplanet is far, far further away than any other planet discovered so far. It is exceedingly hard to spot planets because they are so much smaller compared to the stars they orbit, and they reflect little light. So most exoplanets are detected by looking at the small impacts they have on the brightness of the stars around which they orbit.

This new potential exoplanet in Messier 51, however, was spotted by looking in the X-ray wavelength instead of the visible light wavelength. The team of researchers looked at systems called X-ray binaries, in which a normal star is being consumed by a black hole or neutron star, and is giving off X-rays. The dense black hole or neutron star which is producing the X-rays is a small area, so if a planet passes in front of the system then it could block almost all of those X-rays — which makes it possible for it to be noticed from Earth.

“We are trying to open up a whole new arena for finding other worlds by searching for planet candidates at X-ray wavelengths, a strategy that makes it possible to discover them in other galaxies,” said lead author Rosanne Di Stefano of the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) in a statement.

The team was able to spot such a dip in X-rays from an X-ray binary called M51-ULS-1 in the Messier 51 galaxy. They found a three-hour period during which the X-rays emitted from this binary dropped to zero, suggesting the presence of a planet around the size of Saturn. They did consider whether the drop in X-rays could be due to another source, such as a cloud of dust, but they found the best fitting explanation with their data was the passing of a planet.

This finding is exciting as it indicates a new way to detect very distant exoplanets, however, the authors are careful to state that this is a potential discovery only, and they can’t be sure it definitely is a planet until they can do more research. The problem is that it will take a long time — around 70 years — until the potential planet passes in front of the binary once again.

“Unfortunately to confirm that we’re seeing a planet we would likely have to wait decades to see another transit,” said co-author Nia Imara of the University of California at Santa Cruz. “And because of the uncertainties about how long it takes to orbit, we wouldn’t know exactly when to look.”

But the researchers won’t be defeated by this, and they intend to keep searching archives of X-ray data to look for more candidate exoplanets in other galaxies. “Now that we have this new method for finding possible planet candidates in other galaxies, our hope is that by looking at all the available X-ray data in the archives, we find many more of those. In the future we might even be able to confirm their existence,” said Di Stefano.