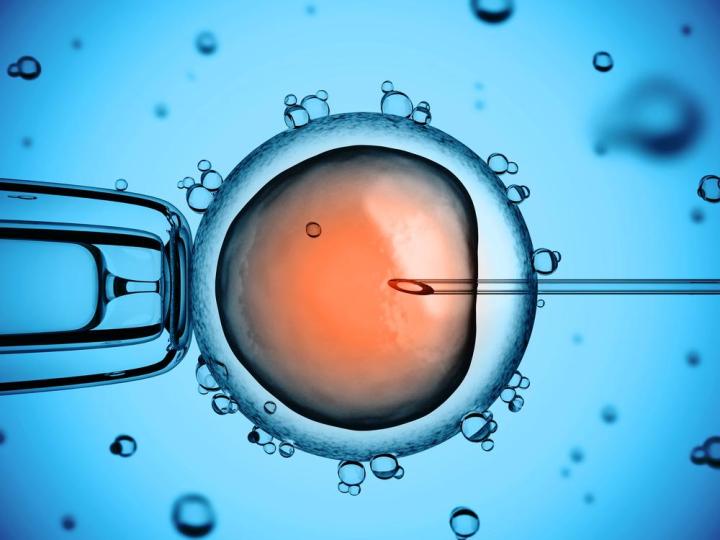

To accomplish this feat, the researchers used a technique called CRISPR, which (in very simple terms) seeks out genes that cause genetically-inherited diseases. The procedure involves injecting embryos with the enzyme complex CRISPR/Cas9, which binds to and splices DNA at specific locations. This complex can be programmed to target problematic genes and replace them with different molecules, which effectively neutralizes them before a person is born. The technique has been demonstrated in animal embryos and in adult human cells, but this is the first published study that deals with human embryos.

In their experiments, the researchers were attempting to edit a gene called HBB, which encodes a protein whose mutations can sometimes trigger a deadly blood disorder. To fix it, they used CRISPR to edit the gene’s molecular makeup — but the procedure wasn’t 100 percent successful.

On a few of the embryos, CRISPR missed its target and edited the wrong sections of DNA. Of the 86 embryos used in the experiment, only 71 survived the procedure, and DNA was successfully spliced in just 28 of them — many of which were shown to contain new and unintended genetic content.

This is problematic because accidental mutations could cause new disorders, with the potential for disastrous and unforeseen effects on coming generations. In this case, there was no intention to permit the embryos to continue to develop. They were grown specifically for experimentation, and were engineered to stop growing at an early stage. Insert your own moral or ethical interpretation here.

The experiment is groundbreaking, for sure — but gene editing like this still isn’t quite ready for prime time. “If you want to do it in normal embryos, you need to be close to 100%,” lead researcher Jinjiu Huang says. “That’s why we stopped. We still think it’s too immature.”

So, while the results are promising, we’re still a few years — if not a full decade — away from Gattaca-style genetic engineering.