The long-delayed James Webb telescope is finally moving toward completion. The telescope recently passed a key round of testing ahead of its planned launch in 2021.

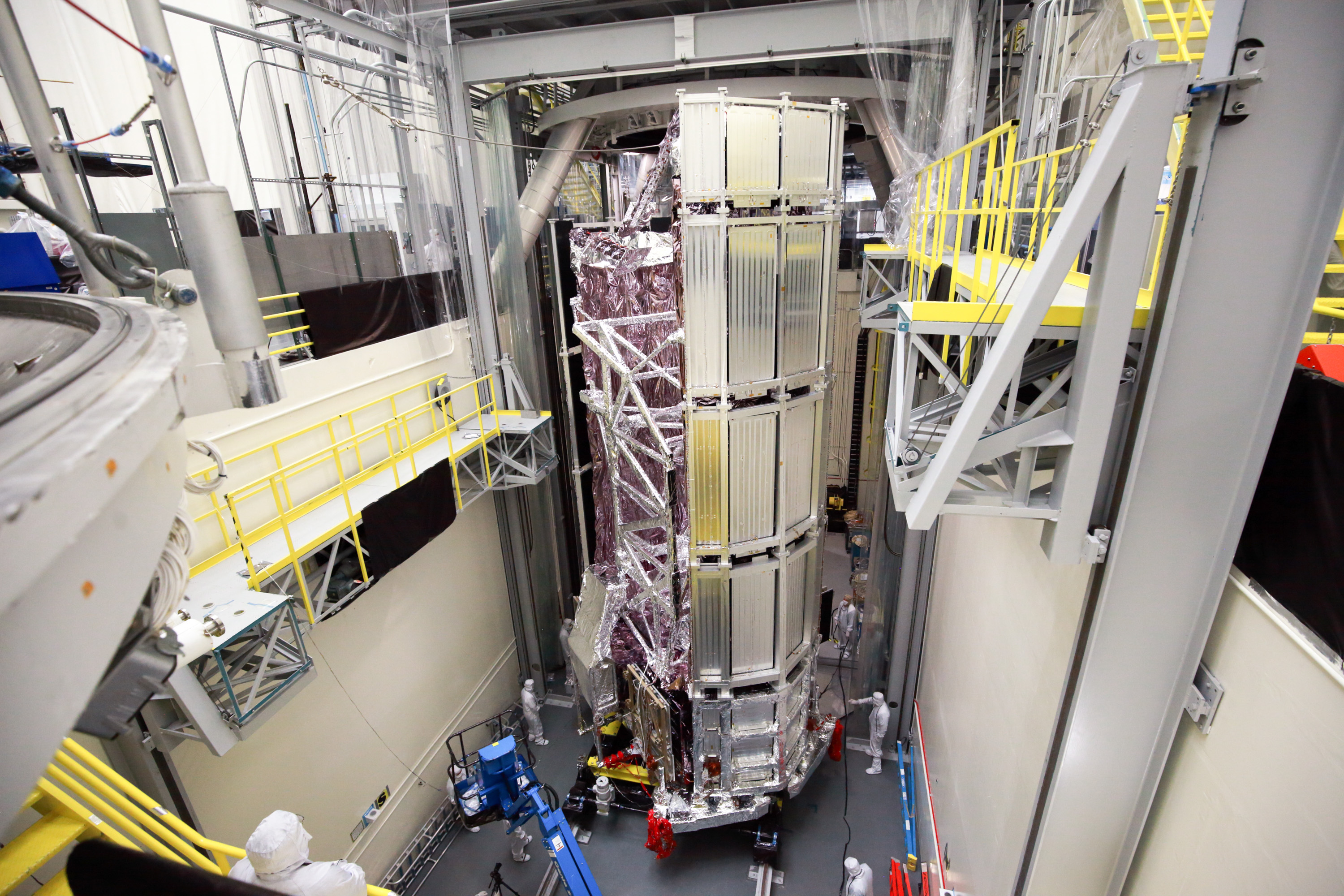

The vehicle that will launch the telescope into space went through vacuum testing, in which the craft is exposed to a simulation of the space environment. This involves the use of a thermal vacuum chamber into which the spacecraft is placed. Engineers can then test its resilience to the extreme temperatures of launch and space, ranging from minus 235 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 148 degrees Celsius) to 215 degrees Fahrenheit (102 degrees Celsius)

The telescope itself went through vacuum testing last year at NASA’s Johnson Space Center. But now the other half of the project, the spacecraft element, has passed its testing at Northrop Grumman as well.

“The teams from Northrop Grumman and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center are to be commended for a successful spacecraft thermal vacuum test, dedicating long hours to get where we are now,” Jeanne Davis, program manager for the James Webb Space Telescope Program, said in a statement. “This incredible accomplishment paves the way for the next major milestone, which is to integrate the telescope and the spacecraft elements.”

The spacecraft element consists of a “bus,” which is the part that flies the telescope into place, and the unique sunshield that will protect the telescope’s delicate circuitry from the heat of the Sun. The sunshield is made up of five layers and spans the size of a tennis court, and is designed to ensure the telescope instruments are kept at the low temperatures required for successful operation.

Now that both parts of the craft have gone through vacuum testing, the next challenge is for the engineers to join the two together. Then a final round of testing can begin, making sure that every part is ready for its big launch. When it launches, it will be the world’s most powerful telescope and will be the successor to the beloved Hubble telescope. It should be able to collect images at a higher resolution and sensitivity, observing some of the most distant objects in the universe.

Editors' Recommendations

- Swatch lets you put a stunning Webb space image on a watch face

- James Webb’s mirrors are almost, but not quite, cooled

- James Webb Space Telescope has gone cold, but that’s good

- James Webb’s MIRI instrument about to face most daunting challenge yet

- Three of James Webb’s four instruments are now aligned