To slightly modify the title of a well-known TV show: Kids do the darndest things. Recently, researchers from Germany and the U.K. carried out a study, published in the journal Science Robotics, that demonstrated the extent to which kids are susceptible to robot peer pressure. TLDR version: the answer to that old parental question: “If all your friends told you to jump off a cliff, would you?” may well be “Sure. If all my friends were robots.”

The test reenacted a famous 1951 experiment pioneered by the Polish psychologist Solomon Asch. The experiment demonstrated how people can be influenced by the pressures of groupthink, even when this flies in the face of information they know to be correct. In Asch’s experiments, a group of college students were gathered together and shown two cards. The card on the left displayed an image of a single vertical line. The card on the right displayed three lines of varying lengths. The experimenter then asked the participants which line on the right card matched the length of the line shown on the left card.

“The special thing about that age range of kids is that they’re still at an age where they’ll suspend disbelief.”

So far, so straightforward. Where things got more devious, however, was in the makeup of the group. Only one person out of the group was a genuine participant, while the others were all actors, who had been told what to say ahead of time. The experiment was to test whether the real participant would go along with the rest of the group when they unanimously gave the wrong answer. As it turned out, most would. Peer pressure means that the majority of people will deny information that is clearly correct if it means conforming to the majority opinion.

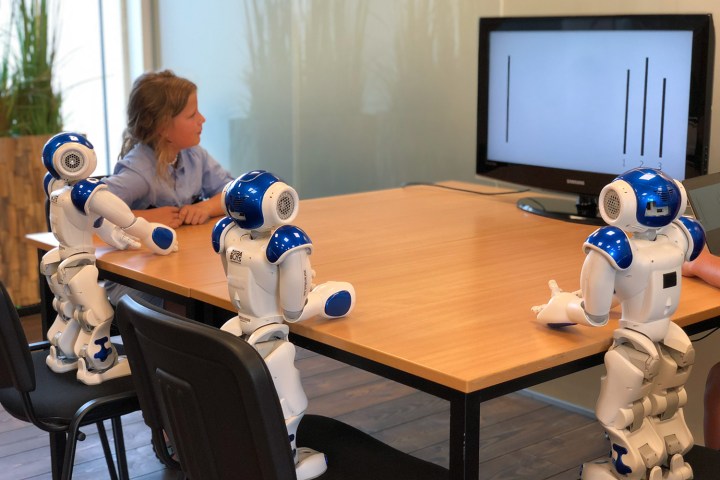

In the 2018 remix of the experiment, the same principle was used — only instead of a group of college age peers, the “real participant” was a child, aged seven to nine years old. The “actors” were played by three robots, programmed to give the wrong answer. In a sample of 43 volunteers, 74 percent of kids gave the same incorrect answer as the robots. The results suggest that most kids of this age will treat pressure from robots the same as peer pressure from their flesh-and-blood peers.

“The special thing about that age range of kids is that they’re still at an age where they’ll suspend disbelief,” Tony Belpaeme, Professor in Intelligent and Autonomous Control Systems, who helped carry out the study, told Digital Trends. “They will play with toys and still believe that their action figures or dolls are real; they’ll still look at a puppet show and really believe what’s happening; they may still believe in [Santa Claus]. It’s the same thing when they look at a robot: they don’t see electronics and plastic, but rather a social character.”

Interestingly, the experiment contrasted this with the response from adults. Unlike the kids, adults weren’t swayed by the robots’ errors. “When an adult saw the robot giving the wrong answer, they gave it a puzzled look and then gave the correct answer,” Belpaeme continued.

So nothing to worry about then? So long as we stop children getting their hands on robots programmed to give bad responses, everything should be fine, right? Don’t be so fast.

Are adults really so much smarter?

As Belpaeme acknowledged, this task was designed to be so simple that there was no uncertainty as to what the answer might be. The real world is different. When we think about the kinds of jobs readily handed over to machines, these are frequently tasks that we are not, as humans, always able to perform perfectly.

This task was designed to be so simple that there was no uncertainty as to what the answer might be.

It could be that the task is incredibly simple, but that the machine can perform it significantly faster than we can. Or it could be a more complex task, in which the computer has access to far greater amounts of data than we do. Depending on the potential impact of the job at hand, it is no surprise that many of us would be unhappy about correcting a machine.

Would a nurse in a hospital be happy about overruling the FDA-approved algorithm which can help make prioritizations about patient health by monitoring vital signs and then sending alerts to medical staff? Or would a driver be comfortable taking the wheel from a driverless car when dealing with a particularly complex road scenario? Or even a pilot overriding the autopilot because they think the wrong decision is being made? In all of these cases, we would like to think the answer is “yes.” For all sorts of reasons, though, that may not be reality.

Nicholas Carr writes about this in his 2014 book The Glass Cage: Where Automation is Taking Us. The way he describes it underlines the kind of ambiguity that real life cases of automation involve, where the problems are far more complex than the length of a line on a card, the machines are much smarter, and the outcome is potentially more crucial.

“How do you measure the expense of an erosion of effort and engagement, or a waning of agency and autonomy, or a subtle deterioration of skill? You can’t,” he writes. “These are the kinds of shadowy, intangible things that we rarely appreciate until after they’re gone, and even then we may have trouble expressing the losses in concrete terms.”

“These are the kinds of shadowy, intangible things that we rarely appreciate until after they’re gone.”

Social robots of the sort that Belpaeme theorizes about in the research paper are not yet mainstream, but already there are illustrations of some of these conundrums in action. For example, Carr opens his book with mention of a Federal Aviation Administration memo which noted how pilots should spend less time flying on autopilot because of the risks this posed. This was based on analysis of crash data, showing that pilots frequently rely too heavily on computerized systems.

A similar case involved a 2009 lawsuit in which a woman named Lauren Rosenberg filed a suit against Google after being advised to walk along a route that headed into dangerous traffic. Although the case was thrown out of court, it shows that people will override their own common sense in the belief that machine intelligence has more intelligence than we do.

For every ship there’s a shipwreck

Ultimately, as Belpaeme acknowledges, the issue is that sometimes we want to hand over decision making to machines. Robots promise to do the jobs that are dull, dirty, and dangerous — and if we have to second-guess every decision, they’re not really the labor-saving devices that have been promised. If we’re going to eventually invite robots into our home, we will want them to be able to act autonomously, and that’s going to involve a certain level of trust.

“Robots exerting social pressure on you can be a good thing; it doesn’t have to be sinister,” Belpaeme continued. “If you have robots used in healthcare or education, you want them to be able to influence you. For example, if you want to lose weight you could be given a weight loss robot for two months which monitors your calorie intake and encourages you to take more exercise. You want a robot like that to be persuasive and influence you. But any technology which can be used for good can also be used for evil.”

What’s the answer to this? Questions such as this will be debated on a case-by-case basis. If the bad ultimately outweighs the good, technology like social robots will never take off. But it’s important that we take the right lessons from studies like the one about robot-induced peer pressure. And it’s not the fact that we’re so much smarter than kids.