The James Webb Space Telescope spends much of its time peering out into distant regions of space searching for some of the earliest galaxies to exist, but it also occasionally turns its sights onto targets a little closer to home. Following up on its image of Neptune released last year, astronomers using Webb have just released a brand-new image of Uranus as you’ve never seen it before.

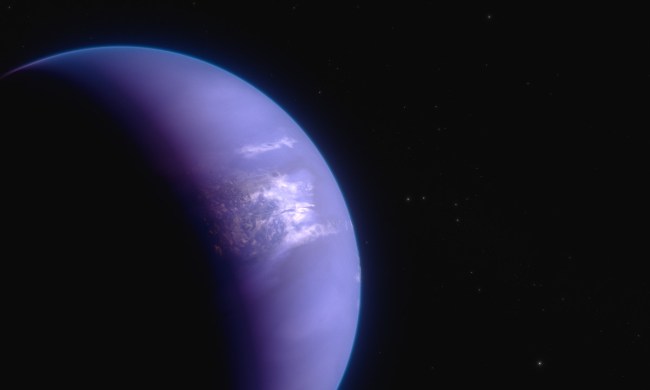

As Webb looks in the infrared wavelength, unlike telescopes like Hubble which look in the visible light spectrum, its image of Uranus picks out some features of the planet which are hard to see otherwise like its dusty rings. Uranus’ rings are almost invisible in the optical wavelength, but in this new image, they stand out proudly.

Uranus has some unusual features compared to other planets in our solar system, as it is almost completely tilted onto its side. Compared to the orbital plane in which the planets sit, Uranus’ axis sits at 98 degrees, meaning that during its northern summer, the sun shines directly onto its north pole and never sets. Researchers believe that this extreme tilt may be due to a massive body that grazed the planet at some point in its history, pushing it onto its side.

That tilt means that when Webb viewed Uranus, it saw its polar cap head-on: The blob of white to the right side of the planet in the image, which is visible throughout summer but disappears in autumn. Looking at this cap using Webb’s sensitive instruments, astronomers were able to see a brighter region in the center of the cap which hadn’t been observed before and also to see other features like two bright clouds (one on the edge of the polar cap and one on the right edge of the planet) which are related to storm activity.

And of course those rings. Uranus has 13 known rings, of which 11 are visible here — though some are bright enough to have merged into each other. These rings are composed of dust, are dotted with small moons, and are thought to be relatively young compared to the planet. Though the small moons within the rings are too faint to be seen, six of the planet’s more distant moons are visible in the wider-view image of the planet.