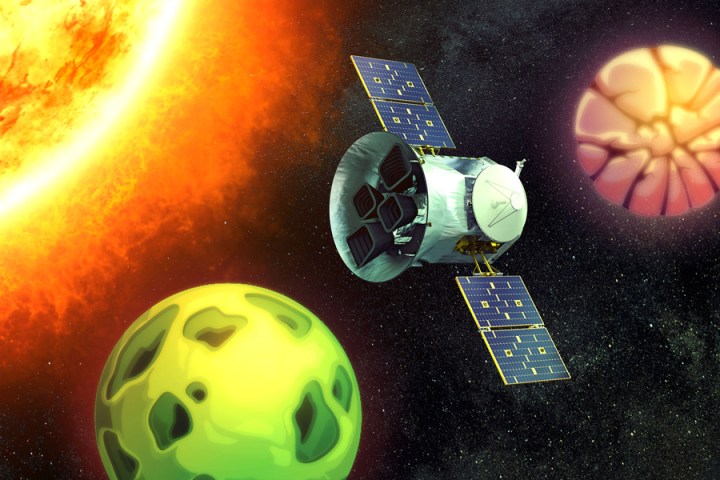

Researchers using NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) have discovered two rocky exoplanets in a system in our cosmic backyard, located just 33 light-years from Earth. These are some of the closest rocky planets discovered to date, orbiting around a small, cool star called HD 260655.

The two planets are of a type called a super-Earth, at 1.2 and 1.5 times the size of our planet, but they aren’t habitable as they orbit close to their star and have high surface temperatures. According to NASA the nearest planet to the star, called HD 260655 b, has a surface temperature estimated at 816 degrees Fahrenheit (435 Celsius), while its companion HD 260655 c is estimated to have a temperature of 543 Fahrenheit (284 Celsius).

Estimating the surface temperature of exoplanets is tricky though because it depends on whether the planets have an atmosphere. In our solar system, for example, Venus is hotter on its surface than Mercury even though it is farther from the sun because its thick atmosphere traps the heat.

So to understand more about exoplanets, we need to measure their atmospheres — something which has historically been very difficult but will be possible with new tools like the James Webb Space Telescope, set to begin science operations this summer.

And these two planets are ideal candidates for studying exoplanet atmospheres, because they are relatively close to us and because the star around which they orbit is bright despite its small size.

“Both planets in this system are each considered among the best targets for atmospheric study because of the brightness of their star,” explained one of the researchers, Michelle Kunimoto of MIT, in a statement. “Is there a volatile-rich atmosphere around these planets? And are there signs of water or carbon-based species? These planets are fantastic test beds for those explorations.”

James Webb will be able to investigate exoplanet atmospheres by looking at the light which shines from a star and passes through a planet’s atmosphere. By splitting this light into a spectrum, researchers can see which wavelengths have been absorbed by particular molecules, and that allows them to work out what the atmosphere is composed of.

There’s no indication yet on whether these two newly discovered planets have atmospheres or not, but they are exciting targets for further investigation.

The research was presented at the meeting of the American Astronomical Society on June 15 and will be published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.