Even though scientists have now discovered more than 5,000 exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system, it’s a rare thing that any telescope can take an image of one of these planets. That’s because they are so small and dim compared to the stars that they orbit around that it’s easier to detect their presence based on their effects on the star rather than them being detected directly.

However, thanks to its exceptional sensitivity, the James Webb Space Telescope was recently able to image two potential exoplanets orbiting around small, cold cores of dead stars called white dwarfs directly.

White dwarfs are the cores that remain after a star, like our sun, comes to the end of its life. In around 5 billion years’ time, our sun will puff up to a much larger size, growing to 200 times its previous radius and engulfing Mercury, Venus, and maybe even Earth before collapsing down to a cool core. In around six billion years’ time all that will remain is this dense core, giving off only residual heat.

Because of the violence of this puffing up and collapsing process, the environments around white dwarfs aren’t very hospitable places for planets. Only a few planet-like objects have been discovered orbiting white dwarfs, though researchers looking at the amount of metal found in white dwarfs suggest that planets may be able to survive the red dwarf phase.

These planets would be tricky to detect because of the dim light given off by white dwarfs, so there could be many of these planets out there, but they are hard for us to spot.

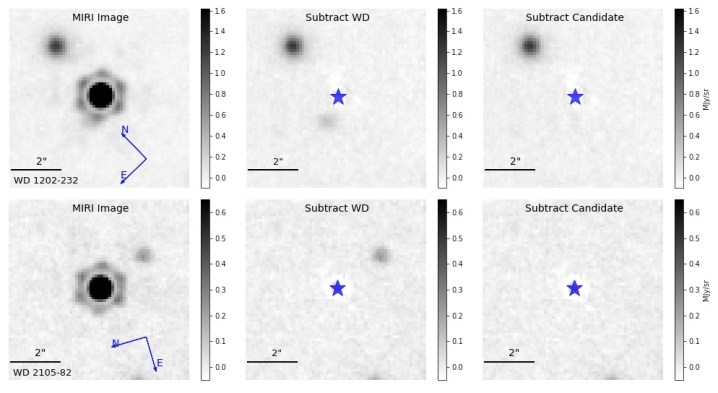

Researchers using James Webb, however, have evidence of what appears to be two giant exoplanets orbiting white dwarfs. They took direct images using Webb’s MIRI instrument, which was sensitive enough to see what appear to be planets even though it doesn’t have a coronagraph — a special type of shade used to block out light from a star.

“The sensitivity and resolution of MIRI along with the light-gathering power of JWST have made it possible to image previously unseen middle-aged giant planets orbiting nearby stars, all without a coronagraph,” the authors wrote in their paper describing the research.

These potential exoplanets are particularly interesting as they give a preview of what could happen to the giant planets in our solar system, like Jupiter and Saturn, in billions of years’ time.”These candidates would represent the oldest directly imaged planets outside our own solar system, and in many ways are more like the planets in our outer solar system than ever discovered before,” the authors write.

The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.