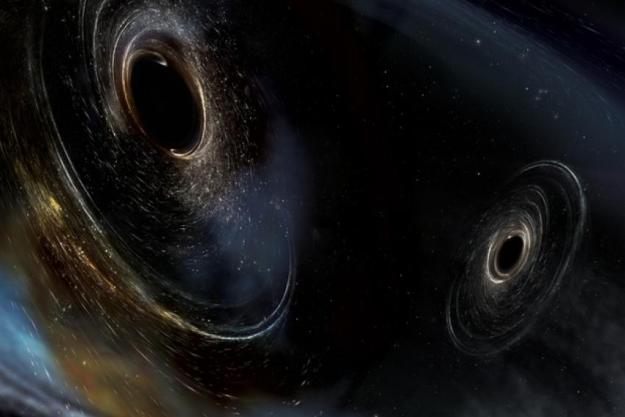

At the center of most galaxies lies a single monster: a supermassive black hole, with a mass millions or even billions of times that of the sun. These lonely beasts typically sit alone in the heart of galaxies, but recent research found two of these monsters nestled close together in the galaxy UGC4211.

The two supermassive black holes originated in two different galaxies which are now merging into one, located relatively close by at a distance of 500 million light-years from Earth. The pair is among the closest black hole binaries ever observed, sitting just 750 light-years apart, and was observed using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

These are hungry black holes as well, as both members of the pair are growing in size. That surprised scientists, as they had expected to find a more sedate pairing. “Simulations suggested that most of the population of black hole binaries in nearby galaxies would be inactive because they are more common, not two growing black holes like we found,” explained lead author Michael Koss in a statement.

It could be that close black hole binaries like this one are actually quite common in the universe. The research is also relevant to our own galaxy, the Milky Way, as we are set to crash into the Andromeda galaxy in around 4.5 billion years’ time, and the merging galaxies of UGC4211 give an idea of what that process could look like.

As well as the data from ALMA, which is a ground-based array of many telescopes looking in the radio wavelength, the researchers used data from other sources like the space-based Hubble telescope which observes in the visible light wavelength, and X-ray instruments which provided another view.

“Each wavelength tells a different part of the story,” said co-author Ezequiel Treister. “While ground-based optical imaging showed us the whole merging galaxy, Hubble showed us the nuclear regions at high resolutions. X-ray observations revealed that there was at least one active galactic nucleus in the system. And ALMA showed us the exact location of these two growing, hungry supermassive black holes. All of these data together have given us a clearer picture of how galaxies such as our own turned out to be the way they are, and what they will become in the future.”

Editors' Recommendations

- Biggest stellar black hole to date discovered in our galaxy

- Nightmare black hole is the brightest object in the universe

- Scientists want your help to search for black holes

- Record-breaking supermassive black hole is oldest even seen in X-rays

- This peculiar galaxy has two supermassive black holes at its heart