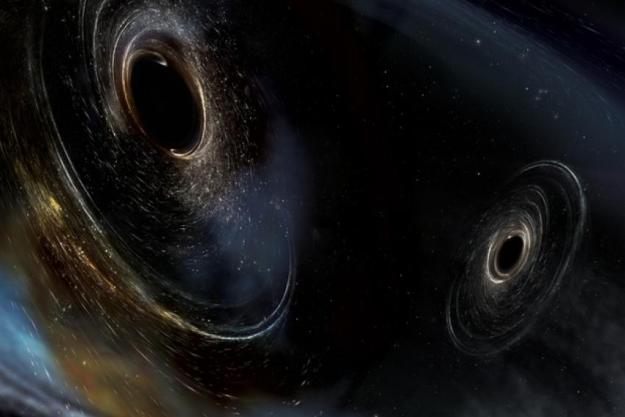

Astronomers have spotted a pair of black holes that are heading for an epic collision. One is a supermassive black hole, the enormous type of black hole which is found at the center of most galaxies, and the other is a smaller companion that is orbiting around its partner and spiraling closer in. Eventually, the two will merge, and studying them now could give clues about how supermassive black holes come to be.

Researchers aren’t sure exactly how supermassive black holes, which are millions or even billions of times the mass of the sun, are created. They think that they might form from the merging of two smaller supermassive black holes, but it’s very rare to spot such a pair, so this new discovery could shine a light on this process.

The pair were spotted by a team of astronomers led by Sandra O’Neill from Caltech. The team observed the pair in a galaxy called PKS 2131-021 using radio telescopes on Earth which can see jets that are ejected from black holes’ event horizons when hot gas hits them. These jets are so powerful they can be detected from Earth, especially if the jets are pointed toward us, forming what is called a blazar.

The team looked at observations of the blazar stretching back over 45 years to identify the pair. They found variations in the brightness of the blazar which fitted a very distinct pattern. “When we realized that the peaks and troughs of the light curve detected from recent times matched the peaks and troughs observed between 1975 and 1983, we knew something very special was going on,” said O’Neill in a statement.

By comparing observations from five different observatories dating back to 1975, the researchers were able to confirm the variations were due to a second black hole tugging on the orbit of the supermassive black hole, as the two orbit each other approximately every two years.

“This work is a testament to the importance of perseverance,” said co-author Joseph Lazio of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in a statement. “It took 45 years of radio observations to produce this result. Small teams, at different observatories across the country, took data week in and week out, month in and month out, to make this possible.”

The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Editors' Recommendations

- Biggest stellar black hole to date discovered in our galaxy

- Nightmare black hole is the brightest object in the universe

- Astronomers spot rare star system with six planets in geometric formation

- This peculiar galaxy has two supermassive black holes at its heart

- Swift Observatory spots a black hole snacking on a nearby star