Something very strange is up with cosmology. In the last few decades, one big question has created a crisis in the field: How fast is the universe expanding? We know that the universe has been expanding since the Big Bang, but the exact rate of this expansion is still not known for certain. The problem is that the rate of expansion seems to be different depending on what factors are used to measure it, and no one is sure why.

Recently, new research using the James Webb Space Telescope has made it clear that this problem isn’t going away any time soon. Webb has refined previous measurements of the expansion rate made using data from the Hubble Space Telescope, and the glaring inconsistency is still there.

The rate of the expansion of the universe is known as the Hubble constant, and there are two main ways in which it is measured. The first way is by looking at distant galaxies, and working out how far away they are by looking at particular types of stars that have predictable levels of brightness. This tells you how long the light has been traveling from that galaxy. Then researchers look at the redshift of that galaxy, which shows how much expansion has occurred during this time. This is the method of measuring the Hubble constant used by space telescopes like Hubble and Webb.

The other method is to look at the leftover radiation from the Big Bang, called the cosmic microwave background. By looking at this energy and how it varies across the universe, researchers can model the conditions that must have created it. That lets you see how the universe must have expanded over time.

The problem is, these two methods disagree on the final figure for the Hubble constant. And as measurement techniques get more and more accurate, the difference isn’t going away.

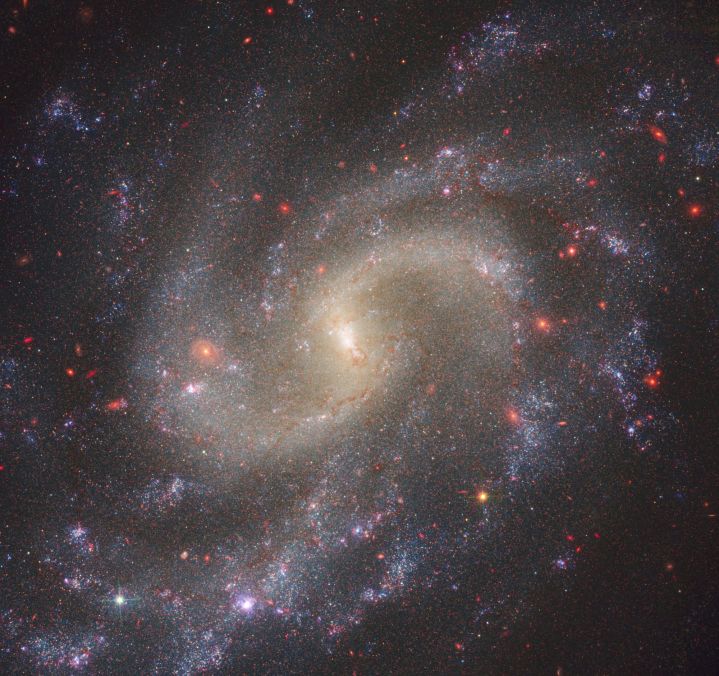

The recent research used Webb to investigate the particular stars used for calculating distance, called Cepheid variables. Researchers looked at the galaxy NGC 5584 to see if the measurements Hubble took of these stars really were accurate — if they aren’t, that could explain the discrepancy in the estimates of the Hubble constant.

The researchers took previous Hubble measurements of the stars and pointed Webb at the same stars, to see if there were important differences in the data. Hubble was designed to look primarily in the visible light wavelength, but the stars had to be observed in the near-infrared because of the dust in the way, so the thought was that perhaps Hubble’s infrared vision was just not crisp enough to see the stars accurately.

However, that explanation wasn’t to be. Webb, which operates in the infrared, looked at more than 300 Cepheid variables, and the researchers found that the Hubble measurements were correct. They could even pinpoint the light from these stars even more accurately.

So to our best knowledge, the discrepancy in the Hubble constant is still there, and still causing a problem. There are all sorts of theories for why this could be, from theories about dark matter to flaws in our theories of gravity. For now, the question remains firmly open.

The research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.